Japan's Comfort Women (28 page)

Read Japan's Comfort Women Online

Authors: Yuki Tanaka

Tags: #Social Science, #Ethnic Studies, #General

As evidence could be provided for only six cases, the author of this report proudly claimed that these figures reflected “the absence of serious crime waves”

in Tokyo for this period.59

Yet there is no doubt that newspaper reports on the increasing number of crimes committed by the occupation forces upset GHQ staff considerably. On September 19, the Office of Supreme Commander of the Allied Power (SCAP) issued a memorandum on the “press code for Japan”60 and started controlling press reports by introducing post-censorship. This “press code” had ten Articles, including the following one:

Japanese women: 1945–1946

125

4

There shall be no destructive criticism of the Allied Forces of Occupation and nothing which might invite mistrust or resentment of the troops.

As a result, the

Asahi Shimbun

was not permitted to distribute its papers for a couple of days between September 19 and 20. From September 22, similar regulations were applied to radio broadcasts. From October 8 pre-censorship was applied to all articles published in five major newspapers. From January 1946, pre-censorship was extended to the publication of journals and magazines, and to the content of films and theatrical plays. This censorship was introduced not only to suppress any information on crimes committed by the occupation troops, but also for many other purposes, such as information about the effects of the A-bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.61 The tight control on information about the increasing number of crimes committed by GIs against Japanese civilians was undoubtedly one of the important roles that this censorship was expected to play.

Therefore, news reports of crimes committed by the occupation forces vanished from newspapers after September 19. After that, we see only articles applauding Americans such as a long article entitled “the Essence of American Democracy”62

published in

Yomiuri HDchi

on September 23, and an article about a US medical officer who saved the life of a sick Japanese girl, which appeared in the

Asahi

Shimbun

on September 26.63

Unfortunately, the most informative official reports, such as the kempeitai’s secret reports,

Chian JDsei

, and the reports prepared by the Police and Security Bureau of the Ministry of Home Affairs, including the documents that Tokk

d

prepared, cover only the first several weeks of the occupation.64 Thus, we do not have comprehensive official documents which could reveal the full extent of sexual violence committed by the US occupation troops against Japanese women.

However, according to statistical data compiled by the Metropolitan Police Office, the following numbers of rape and attempted rape by GIs in the Tokyo and Kanagawa areas were reported to police between March and September 1946:65

Table 5.1

Reported cases of rape and attempted rape in the Tokyo and Kanagawa areas, March–September 1946

Month

Reported cases

Rape

Attempted rape

March

15

10

April

15

20

May

35

30

June

30

30

July

20

20

August

30

30

September

20

25

126

Japanese women: 1945–1946

These figures, which record only a small fraction of cases of rape and attempted rape, indicate that, even a year after the beginning of the occupation, GI rape was still a serious problem for Japanese women.

In addition to the US forces, the BCOF (British Commonwealth Occupation Forces) also participated in the occupation of Japan from early February 1946.

The advance party of the BCOF, sent from Hong Kong, arrived at Kure, the port of Hiroshima, on January 31, 1946. On February 13, 1,000 Australian troops landed at Kure. By June the numbers of the BCOF had increased to 39,000. They were composed of British, Australian, New Zealand, and Indian soldiers. The largest group was 12,000 Australians – 32 percent of the BCOF.

The BCOF was stationed in the Chugoku area of Honshu Island and on Shikoku Island. They functioned as the supplementary troops for the US forces. The bulk of the troops, however, were concentrated in Kure and Fukuyama of Hiroshima prefecture.66

According to statistical data compiled by the Hiroshima prefectural police office, 263 crimes by occupation forces were reported to police in the prefecture between October and December 1945. Among them were 84 rape cases. As these crimes were committed before the BCOF’s arrival, it is presumed that the offenders were mostly Americans. In 1946, 800 crimes were reported, of which 303 were rape cases – the single most common crime, consisting 38 percent of the total crime cases reported to the police. This figure is twice the rate of the second-most-common crime – extortion.67 Most of these crimes are believed to have been committed by members of the BCOF because the majority of the US

occupation troops had left Hiroshima prior to the BCOF’s landing.

Unfortunately, unlike the cases in the Tokyo and Kanagawa areas, detailed official reports on individual cases of sexual crimes committed by the Allied soldiers in Hiroshima prefecture are not available. However, in his memoirs, Allen Clifton elaborates upon some cases that he investigated during the occupation. Clifton was a young Australian junior officer of the BCOF who acted as an interpreter and criminal investigator. The following passages are some extracts from his memoirs:

I stood beside a bed in a hospital. On it lay a girl, unconscious, her long, black hair in a wild tumult on the pillow. A doctor and two nurses were working to revive her. An hour before she had been raped by twenty soldiers. We found her where they had left her, on a piece of waste land.

The hospital was in Hiroshima. The girl was Japanese. The soldiers were Australians.

The moaning and wailing had ceased and she was quiet now. The tortured tension on her face had slipped away, and the soft brown skin was smooth and unwrinkled, stained with tears like the face of a child that has cried itself to sleep.

Staying indoors was not sufficient to give women protection. One evening a young married woman was reading a book in bed in a hotel. Her husband was absent for the night on business. In the next room, separated only by

Japanese women: 1945–1946

127

the paper sliding partitions, a party of Japanese men were playing cards. It was a hot night and she fell asleep in the middle of her reading, with the light still burning. She awoke a little later to find a huge Australian soldier kneeling beside her, and another swaying in the doorway, his drunken leer telling more clearly than any speech or gesture what was to follow . . .

The men in the next room heard and watched; saw all and did not intervene. To call them cowards would be to presume the obvious and improbable. The reason lay elsewhere: in their blind unquestioning accept-ance of instructions from the Government that placed the Shinchugun [occupation forces] beyond criticism and Japanese justice . . .

Instead the Japanese went and told the police. The police, having no power, could do no more than inform us, when it was too late . . .

At the Court Martial that followed, the accused was found guilty and sentenced to ten years’ penal servitude. In accordance with army law the court’s decision was forwarded to Australia for confirmation. Some time later the documents were returned marked “Conviction quashed because of insufficient evidence.”68

Testimonies of victims of sexual violence committed

by the occupation troops

The official documents conceal important dimensions of how sexual violence was committed by the occupation troops. Rape of Japanese women took various forms. It is necessary to closely examine first-hand testimonies of the victims of sexual crimes in order to understand the nature of the crimes committed.

A number of Japanese publications on this subject were published between the late 1940s and early 1950s – shortly after the Press Code by GHQ was removed.

Among those publications, the most reliable are

Nippon no TeisD

( Japan’s Virtue), published in 1947, and

Kuroi Haru

(Black Spring), published in 1953. Both include a number of first-hand testimonies of victims of sexual violence committed by GIs.

According to some testimonies, members of the military police, who were supposed to be responsible for investigating rape cases and arresting rapist soldiers, themselves sometimes raped Japanese women. One woman, Ono Toshiko (pseudonym), states in her testimony that she was a victim of rape by three military policemen in Kyoto. Shortly after Toshiko’s parents were killed in the firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945, she moved to Kyoto to live with her aunt’s family. She continued to live there after the war as she had nowhere else to go.69

She does not give an exact date when it happened, but one evening a Japanese police officer came to see Toshiko and informed her that the military police were investigating her on suspicion of illegal possession of US military goods.70

Stealing of military goods by GIs was rampant in the early period of the occupation. Goods such as tinned food, blankets, and clothes were stolen from the base stores or from trucks and freight trains while in transit from one place to another. They were then sold to Japanese black-market brokers, who in turn sold them to black market dealers.71 Many Japanese bought these items at high 128

Japanese women: 1945–1946

prices, given the acute shortage of essential goods at that time. The military police arrested GIs involved in stealing large quantities of military goods and also arrested black-market brokers, who operated the business widely, but they rarely arrested individuals who had purchased items at black-market stalls. Given that the Japanese police were aware of the US military police policy towards individuals accused of purchasing stolen goods, the Japanese officer must have suspected the military policemen’s real intentions. However, he probably could have done nothing but obey their orders.

The police officer took Toshiko to the three military policemen, who were waiting for her in an army jeep outside her aunt’s house. Leaving the Japanese policeman behind, they took her a long way out of the city and repeatedly gang-raped her until midnight. When they had finished, one of them offered her a cigarette, which she refused. Becoming angry, the military policemen stuck the cigarette butt on her stomach and left her alone in the bush.72

According to various other testimonies, it seems that rape by members of the military police was far from rare. There is even testimony that one military policemen, who interviewed a rape victim in order to collect evidence, later returned and raped her.73 One Japanese policeman complained to a Japanese interpreter employed by the US occupation troops that if the police reported a rape case to the military police they usually showed very little interest. On the other hand, they would immediately investigate other crimes, such as arson.74 In rape cases which implicated members of the military police, victims had nowhere to go because the Japanese police had no power to interrogate American suspects.75 It is very difficult to determine the prevalence of rape by military police as there are very few official documents about the problem – either on the Japanese side or on the US side.

Another type of rape which is missing in the official documents, but which is confirmed by testimonies of many victims, is the rape of young Japanese women employed at various offices of the occupation forces. Each military base employed numerous women as telephone operators, typists, and in other office work. Newly recruited Japanese women were often subjected to rape by occupation soldiers and officers. In other cases women were deceived into having sexual relationships on false promises of marriage.

A woman under the pseudonym of Kawabe Satoko was employed as a telephone operator at a US occupation base near her home. Within a few weeks of being employed she found out that many of her colleagues had been raped by GIs, especially during night-shift work. She was surprised to learn that some perpetrators offered tinned food to their victims as a token gesture of apology.

Perhaps the GIs thought that this changed their actions from rape into commer-cial sex,

i.e.

the familiar transaction of prostitution except for the fact that it was paid for with goods, not money. Some victims reported such incidents to the local police office only to be told by the police that it was their own fault and to be careful to avoid being raped.76

Shortly after starting work, Satoko became friendly with a sergeant, her supervisor, who was particularly kind to her and who always tried to protect her. After

Japanese women: 1945–1946

129

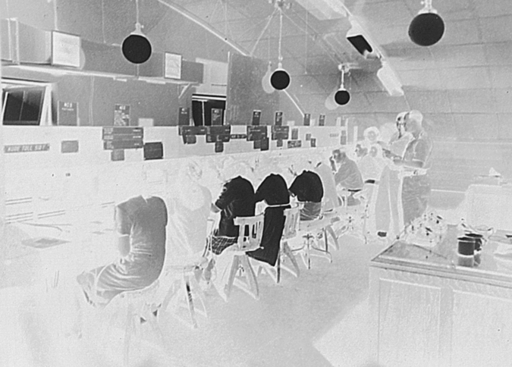

Plate 5.5

Japanese young women working as telephone operators at the headquarters Signal Regiment, BCOF in Kure in September 1948. Many Japanese employees of the occupation forces were victims of sexual harassment.