Jackie and Campy (20 page)

Robinson also prepared Black for the racial abuse he would suffer when the Dodgers played on the road. Once, when the Dodgers traveled to Philadelphia to play the Phillies, a leather-lunged fan spotted Black following Robinson onto the playing field and yelled out, “Hey! There’s Robinson, King of the Niggers, with a little baboon right behind him!” Black, noticeably upset by the remark, turned to Jackie, who calmed him down. The fans in other cities would mockingly sing the Negro spiritual “Old Black Joe” when the rookie pitched. Black, an imposing six-foot-three-inch hulk, would become agitated, but Jackie always managed to refocus

him.

61

“If it wasn’t for those talks with Jackie,” admitted Black, “I don’t think I could have turned the other cheek so many times.

62

Campanella, briefly a teammate of Black’s on the Elite Giants, also endeared himself to the rookie pitcher by warning him about the ever-present vices of loose women and alcohol. He also taught the youngster how to pitch under pressure. “It didn’t take long for Joe to love Campy,” said Carl Erskine. “All of the veteran pitchers gave Joe the same advice. We told him to listen to Roy, follow whatever he says, and throw with confidence. Both Jackie and Roy took young Joe under heir wings and made him an instant star.”

63

With pitching ace Don Newcombe serving in the military overseas in Korea, Black stepped up in 1952. He won fifteen games for the Dodgers, saved another twenty-five, and was voted Rookie of the Year by the sportswriters.

64

There were occasions, however, when Campy and Jackie gave mixed signals to their protégés because of their diametrically opposed approaches to civil rights. At the beginning of the 1953 season, for example, Brooklyn manager Charlie Dressen moved Robinson from second to third base to make room for a younger black infielder, Jim Gilliam. Dressen, a big Robinson fan, was looking out for his star player as well as hoping to improve the team offensively. He realized that Jackie was getting older and having trouble with his knees, which limited his mobility. Playing third wouldn’t be as stressful on his legs because he wouldn’t have to turn the double-play, and Dressen could still keep his productive bat in the lineup. Gilliam, on the other hand, had a talent for getting on base and stealing, ideal qualities for a lead-off hitter. Though he didn’t have a real strong arm and could not turn the double-play smoothly, the rookie would make up for it with his sure-handed fielding and intelligence. In fact Gilliam would go on to become the National League’s Rookie of the Year in 1953. The odd man out was thirty-four-year-old Billy Cox, considered the best defensive third baseman in the game, but a .250 hitter at the time. Cox was infuriated by the move, especially being replaced by a black man. Nor were his roommate, Preacher Roe, a southerner, and Carl Furillo, a fellow Pennsylvanian, very happy about Dressen’s decision. Although all three players had, at one time or another, expressed their disenchantment about playing on the same team with blacks, they made a concerted effort to get along with their African American teammates until now. Apparently spring training was an especially tense period when Robinson and the

others made veiled and accusatory references about the situation. Finally, Campanella, having heard enough, took it upon himself to bring the focus back to the team. “You guys can be wrong, but don’t be loud wrong,” he snapped behind the closed doors of the clubhouse. “Settle it now and get out on the field because we have a game to win.” Shortly afterward Cox returned to third base and Robinson shifted to left field.

65

But the incident underscored the differences between Campanella, who placed team success above individual differences, and Robinson, who could be prickly with anyone who snubbed him. It also revealed the latent animosity that existed over integration among some of the Dodgers and couldn’t help but send mixed signals to the younger black players on the team.

On another occasion, Robinson, in an effort to show leadership, reinforced the infamous reputation he’s established for baiting umpires. During a 1954 game against the Cubs at Wrigley Field, Duke Snider hit what appeared to be a home run into the left-field bleachers. But the ball bounced back onto the field, and umpire Bill Stewart ruled it a double. Robinson believed that a fan had interfered with the ball and that the hit should be ruled a homer. Charging the field to protest, Jackie assumed his teammates would follow him out of the dugout. To his surprise, no one did. Walter Alston, the Dodgers’ new manager, stood in the third-base coaching box, hands on hips, staring angrily at Robinson. Regrouping, Robinson trotted out to Stewart, said a few quiet words, and returned to the dugout. He later admitted that it was a “humiliating moment” that only served to reinforce the “hothead, umpire-baiting label” that had been imposed on him by the press. Angered by Alston’s refusal to support him, Jackie swore that it would be the last time he would “fight the team’s battles.”

66

The most troubling incident, however, came during the Dodgers’ trip to St. Louis that season. Whenever the team played in St. Louis the white players stayed at the Chase Hotel, which refused to accommodate African Americans. Robinson, Campanella, and the younger black players were forced to stay at the Adams Hotel, a black establishment with no air-conditioning or any of the other conveniences of the Chase. Perhaps inspired by the

NAACP

’s challenge that same year to overturn the separate-but-equal doctrine in

Brown v. Board of Education

, Jackie decided to challenge Jim Crow. “Jack got off the train in St. Louis,” recalled

Pee Wee Reese, “and said to me, ‘I’m going to the Chase with you.’ Roy Campanella, Newk and Gilliam told him not to do it. They said they were doing all right and asked him not to rock the boat. But Jackie said, ‘You do whatever you want, but I’m going to the Chase.’ Then he got on the bus with all the white players, went right into the hotel and tried to register.”

67

Robinson told a different story, though.

According to Jackie, he only confronted Campanella, and it was 1955, the year

after

he’d challenged the Chase and won. Newcombe and the other black Dodgers decided to join him at the Chase, but Campy still refused as a “matter of principle since they hadn’t wanted [him] in the past.” Robinson, frustrated, told Campanella that he “had no monopoly on pride” and that “baseball hadn’t wanted him in the past but that he was in the game now.” He added that “winning a victory over the Chase Hotel” meant that all the Dodgers were “really becoming a team [since] all members would be treated equally.” Robinson also insisted that integrating the Chase allowed “all blacks, not just those in baseball, to stay in a decent hotel.” But Campy dismissed him, muttering, “I’m no crusader.”

68

Years later Campanella agreed that the incident took place in 1955, after Robinson had integrated the Chase. But he insisted that the hotel still prohibited blacks from eating in the dining room, sitting in the lobby, or swimming in the pool. Campy also stated that Newcombe and Gilliam decided to stay with him at the Adams, and when Robinson approached them, he replied, “I’m not talking for anybody else; only for myself. It’s got to be the whole hog or nothing for me. As long as there’s any kind of discrimination, you can leave me out. Besides, I’ve been coming to St. Louis for seven years and if they didn’t want me all this time, then I don’t want them now.”

69

There is yet another version of the story, according to Don Newcombe, who claims that both he and Robinson integrated the Chase in 1954. Newcombe, angered at being treated like a second-class citizen after he had served in the military, insists that he was the one who came up with the idea of challenging Jim Crow and that Jackie joined him. “We walked right through the front door,” recalled Newcombe, “and everyone was looking at us as we waited for the manager. He took us into the dining room and offered us a cup of coffee.”

“Do you know why we’re here?” asked Jackie.

“I think I have an idea,” replied the manager, “but why don’t you tell me.”

“Don and I want to know why after all these years we haven’t been able to stay at your hotel,” Robinson explained. “Don just got back from two years of service to his country. He’s mad, and he wants to know. So do I.”

Embarrassed, the manager said, “The only thing I can think of, gentlemen, is we don’t want you in the swimming pool.”

Amused by the response, Jackie admitted that he didn’t know how to swim. “I never swim during baseball season,” added Newcombe. “Afraid to hurt my arm.” “And just like that,” according to the Dodgers’ ace pitcher, “the manager allowed us to stay at the Chase.”

Newcombe insisted that he and Jackie invited Campanella and Gilliam to join them, but they both refused on principle.

70

“So me and Jackie moved into the Chase,” said Newcombe. “The thing is, then, and in all the years we stayed there after that, they never gave us a room on the side of the hotel where the pool was located. We had our ideas why. That bigot didn’t want us looking at those pretty white women walking around in their bikinis. But what he didn’t know was that I had women in my room all the time. Black women, white women, all kinds. That bigot should have come to my room one night and seen what was going on.”

71

Monte Irvin questions the validity of Newcombe’s account. “It doesn’t sound like Newcombe,” said Irvin when he learned of the black pitcher’s alleged attempt to integrate the Chase with Robinson. Newcombe had plenty of disagreements with Jackie. He preferred to just play with him on the field and then go his own way. Like Campy, Newcombe didn’t appreciate Jackie’s attitude. They both saw him as aggressive and “stand-up-ish” and they resented his efforts to make them “the same way he was.”

72

Regardless of which version of the story is accurate, the Chase Hotel incident was the breaking point in the Campanella-Robinson relationship. It underscored the incompatibility of the two players and their different approaches to integration and threatened to divide the black Dodgers into two rival camps: those who supported Campanella and his accommodationist philosophy and those who sided with Robinson and his belief that racial discrimination must be challenged directly whenever possible. Afterward neither man even pretended friendship. They tolerated each other on the playing field for the good of the team and kept their distance from each other off the diamond in order to avoid further acri

mony. Making matters worse was the reality that both players were aging and they still had yet to win a World Series.

“Wait ’til next year!” might have been a rallying cry for the Dodgers faithful, but it was a perennial reminder that the team couldn’t defeat the New York Yankees in the Fall Classic. In fact, by 1955 the Dodgers hated the Yankees as much as if not more than they hated their National League rivals, the New York Giants. In 1947, Robinson’s rookie year, the Dodgers lost to the Bronx Bombers in an exciting seven-game series. The two teams met again in the 1949 Fall Classic, and Brooklyn went down to defeat in just five games. It took the Dodgers three more seasons before they could face the Yanks again. Although Brooklyn held a 3–2 lead after five games, the Yankees came back to take the final two and clinch the world championship. In 1953 the Dodgers posted a club record 105 wins and cruised to the pennant by thirteen games. But again the Yankees took the World Series in six games. Manager Charlie Dressen’s patience was wearing thin. Despite the fact that he had piloted the club to two straight World Series appearances, Walter O’Malley offered him nothing more than the usual one-year contract. In 1954 Dressen said he wouldn’t stay on unless he was given a three-year deal. O’Malley let him go and signed Minor League skipper Walter Alston, who wasn’t so demanding.

73

While Campanella was elated to be reunited with his old manager from Nashua, New Hampshire, Robinson and Alston clashed from the start. Jackie had difficulty respecting the authority of a manager whose entire Major League career consisted of one at-bat and whose decisions he considered “boneheaded.”

74

In addition, Alston, a man of few words, did not create a favorable impression when, prior to spring training, he met with his veteran team and told them, “I’ve read a lot of clippings about how great this team is. But I haven’t seen it. You guys know what it takes to win. I don’t give pep talks. You either do it, or we get someone else. Meeting’s over.”

75

Robinson was uncertain if he had the physical or emotional stamina to play baseball. At thirty-five, he was past his prime as an athlete, and an ongoing battle with diabetes was taking its toll. He was also tired of all the acrimony that had surfaced between him and Campanella. Nor did he have much patience for O’Malley or the intrusive press. Realizing that the prospect of securing an administrative position with the Dodgers—or any other team—was slim, Jackie began to ponder life after baseball.

Hoping to find employment that would be financially rewarding as well as allow him to continue his active role in civil rights, Jackie instructed his lawyer, Martin Stone, to put out feelers in private industry.

76

The man who broke baseball’s color barrier was planning to retire from the game whose history he had forever changed.

8.

Breakup

The 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers were not only one of baseball’s greatest teams, but they have also been mythologized in history as “America’s team.” They symbolized the community and its values as well as the success of integration. During the spring, summer, and early fall, residents flocked to Ebbets Field to cheer on their beloved “Bums” and enjoy the circus-like atmosphere. Others sat on the front steps of their brownstones and listened to the game, babysitting their kids and their neighbors’. The Dodgers, who fielded white, black, and Hispanic role models, lured teenagers away from crime and juvenile delinquency. Even during the winter months, when baseball was dormant, Brooklynites seemed to talk about nothing but the game in anticipation of what the upcoming season might bring. Brooklyn took the Dodgers to their hearts; as a result, an ethnically and racially diverse community was able to transcend the bigotry and prejudice that plagued the rest of the nation. As the first integrated team in the Majors, the Dodgers became easy targets for the intolerance of opposing teams and their fans. Determined to see the noble experiment succeed, Brooklyn’s “Boys of Summer,” rallied together for support. In the process Ebbets Field became a microcosm of the American Dream, where an integrated community of fans enjoyed a common interest in which everyone could be on an equal footing. The love affair reached a climax in 1955, when the Dodgers captured their first and only World Series. The mythology still endures more than half a century later, a reminder of an integrated America’s unlimited potential for social justice.

1

In fact the 1955 Dodgers were a veteran team with star players past their prime. With the exceptions of Sandy Amoros, Jim Gilliam, and Duke Snider, who were in their mid-to-late twenties, the average age of the starting line up was thirty-four.

2

Four of the eight regulars—Robinson, Campanella, Snider, and Gil Hodges—had been signed and developed by Branch Rickey, who departed five years earlier for Pittsburgh. Another regular, Pee Wee Reese, the thirty-six-year-old team captain, had been the Dodgers’ starting shortstop for fifteen years and was on the downside of his playing career. Robinson, also thirty-six, was a “tiring third baseman” with a portly physique. The constant racial abuse he suffered—and provoked—had taken its toll physically. His hair had grayed and his legs, the foundation of his success as a base stealer, were betraying him.

3

Jackie kept his diabetes a secret from teammates as well as Dodgers ownership and management, fearing that knowledge of it would jeopardize his career.

4

He refused to take that risk as long as baseball was his livelihood and a critical forum for civil rights. He was proud of his role in integrating the national pastime and could see the fruit of his effort on the Dodgers’ roster, which featured six players of color, including himself, Campanella, Don Newcombe, Joe Black, Gilliam, and Amoros. Jackie also knew that each of those players deserved to be in the big leagues, with three

MVP

Award winners and four Rookies of the Year among them.

5

As a result, he entered the ’55 campaign struggling with mixed emotions over whether he could do more for civil rights as a ballplayer or in the private sector.

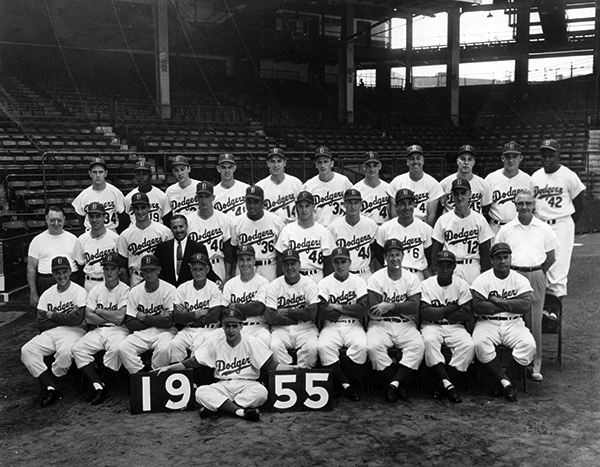

20.

The 1955 world champion Brooklyn Dodgers (season record: 98-55). Seated: batboy Charlie DiGiovanni. Bottom row (

left to right

): George Shuba, Don Zimmer, coach Joe Becker, coach Jake Pilter, manager Walter Alston, coach Billy Herman, captain Pee Wee Reese, Dixie Howell, Sandy Amoros, Roy Campanella. Middle row (

left to right

): clubhouse attendant John Griffin, Carl Erskine, Sandy Koufax, Lee Scott (in suit), Roger Craig, Don Newcombe, Karl Spooner, Don Hoak, Carl Furillo, Frank Kellert, trainer Harold “Doc” Wendler. Top row (

left to right

): Russ Meyer, Jim Gilliam, Billy Loes, Clem Labine, Gil Hodges, Ed Roebuck, Don Bessent, Duke Snider, Johnny Podres, Al Walker, Jackie Robinson. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York)

Campanella, at age thirty-three, was also struggling. Hampered by hand injuries that had limited his playing time the previous year, he saw his batting average slip to .207. Without Campy’s powerful bat, the Dodgers finished a disappointing five games behind the New York Giants, who went on to face the Cleveland Indians in the 1954 World Series. No doubt his five-foot-nine-inch frame was beginning to feel the effects of his 220 pounds in the ongoing battle he waged against his weight. Sportswriters were beginning to wonder if the constant physical demands of catching had finally taken their toll.

6

Though O’Malley had recently signed him to a $45,000 contract, Campy, probably embarrassed by the off-year, told the Dodgers’ owner that he’d “play for nothing if he had to.”

7

More troubling, the Dodgers struggled with the personal animosity Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella harbored against each other. The feud had become a cold war, the two star players largely ignoring each other off the field and barely tolerating each other on it. Teammates and the beat writers were well aware of their mutual disdain, which exacerbated the inevitable tensions that surface among twenty-five players with different backgrounds over the course of a 154-game season.

8

The feud affected at least one other relationship on the team, that between Robinson and manager Walter Alston, a big fan of Campanella. It began during an exhibition game in Montgomery, Alabama, when Jackie was benched for a younger third baseman, Don Hoak. Disgusted by the move, he asked sportswriter Dick Young, who had a talent for getting the inside scoop, if he had heard how Alston was planning to use him that season, but Young said he had not. “When I’m fit,” said Robinson, “I’ve got as much right to be in the line-up as any man on this club, and Alston knows that. Or maybe he doesn’t know that.” The next day the discussion appeared in the

New

York Daily News

. Alston was enraged: “If Robinson has any complaints, why the hell doesn’t he come to me and not tell them to a writer? Only two days ago he said he had a sore arm and wanted to go to a doctor in New York. If he was ready to play, why not tell me?”

Instead of dropping the matter, Robinson fanned the flames by responding, “I believe it’s the manager’s job to know the physical condition of his players. I’ve been in shape all spring. I just can’t play one day and then sit on the bench four days and do a good job.”

Alston was in a precarious position. He realized that if he didn’t stand up to Robinson, he’d lose the respect of all his players. On the other hand, if he did challenge Jackie, he’d lose face among the veterans. Determined to cut his losses, Alston, known for his brute strength, challenged Robinson to a fight. Words were exchanged as the two men positioned themselves for blows before Campanella interceded. “When are you guys going to grow up?” he asked. “We came here to play ball not fight.”

9

Throughout the 1955 season the two men remained resentful of each other. Alston, who believed that the aging Robinson should be a utility man, platooned him at third base with Hoak, limiting Jackie’s playing time to 105 games. The decision infuriated Jackie, who already viewed Alston as a “usurper,” the man who “stole” his friend Charlie Dressen’s job. Sometimes Jackie was openly critical of the manager, complaining about his “boneheaded judgments,” his inability to “remain cool under pressure,” and his leniency with umpires. On other occasions he was silently resentful of Alston, which could be worse since Robinson’s emotions were always close to the surface.

10

Interestingly another team conflict seemed to unite the black Dodgers, marginalizing the impact of the Robinson-Campanella feud, at least for a time. It involved rookie pitcher Sandy Koufax, a Jew and an extremely talented prospect. Signed by the Dodgers for an annual salary of $6,000 with a $14,000 bonus—a considerable amount considering the total Brooklyn payroll was just $500,000—Koufax instantly created jealousy among some of the veterans who were paid less.

11

Despite his request to go to the Minors, the young hurler, like all “bonus babies,” had to remain on the Major League roster or the Dodgers would risk losing him to another team. Koufax’s very presence triggered the widespread anti-Semitism that existed in baseball itself and divided the team along racial

lines. Some white teammates spurned him as a “moneyed kike,” while the black Dodgers rallied to his defense, having been the victims of prejudice themselves. Robinson, Campanella, Gilliam, Black, and Newcombe went out of their way to protect Koufax. Robinson was especially critical of Alston, who rarely used the rookie pitcher in spite of his potential. According to Tom Villante, a member of the Dodgers’ broadcast team, Jackie “appreciated Sandy’s talent” and he “already disliked Alston, so it was easy for him to take [Koufax’s] side.” “The fact that Sandy would every so often show this terrific flash of brilliance and pitch a terrific game,” said Villante, “and then Alston wouldn’t pitch him again for thirty days irked Jackie. It only confirmed, in Jackie’s mind, just how dumb Alston really was.”

12

The other black Dodgers were more subtle in their support of the young Jewish star. They embraced him as one of their own, inviting him to socialize with them and offering him constant encouragement. Some were astounded that after everything the team had experienced with the integration process there were still white Dodgers who openly discriminated against a teammate. “I couldn’t understand the narrowness of some of our star players who talked about Sandy as a ‘Jew bastard who’s gonna take somebody’s job,’” recalled Newcombe. “They hated Jews as much as they hated blacks. You think of crackers being from the South, but these guys were from California and other places. It was because of that bigotry that we took care of Sandy.”

13

Despite the problems with team chemistry, Brooklyn somehow managed to record its most productive season ever.

The Dodgers opened the 1955 season by reeling off ten straight wins and taking twenty-two of their first twenty-four games. By July 4 they found themselves in first place with a twelve-and-a-half-game lead. Not even a mid-August slump could dislodge them as they completed the season thirteen and a half games in front of second-place Milwaukee.

14

“We were no challenge to the Dodgers,” recalled Hank Aaron of the Braves, who reluctantly admitted to keeping a scrapbook of the team. “Don Newcombe was the best pitcher in the League that season, and with Campy and Jackie they were never out of first place.”

15

Indeed Newcombe was the ace of a formidable pitching staff, posting a 20-5 record for an .800 winning percentage. With a devastating fastball and a curve that broke so sharply umpires suspected him of throwing a spitter, Newk hurled seventeen complete games and recorded 143 strikeouts and a 3.20 earned

run average. The only pitcher to come close that season was the Phillies’ Robin Roberts, who went 23-14 with a .622 winning percentage. Either one would have been worthy of the Cy Young Award if it had existed at the time.

16

Carl Erskine, famous for his overhand curveball, contributed another eleven victories and pitched 195 innings, recording 84 strikeouts with a 3.78

ERA

. Twenty-two-year-old Johnny Podres went 9-10 with 114 strikeouts and a 3.96

ERA

, and Clem Labine, known for a sinking fastball, was the league’s top reliever, with thirteen victories and eleven saves in sixty appearances.

17

Campanella anchored the team, both offensively and defensively. He hit .318, and his short, powerful swing connected for 32 home runs and 136

RBI

s, impressive statistics that secured a third

MVP

Award.

18

Although Robinson batted just .256, the lowest of his career to that date, he still contributed 81 hits, including 8 home runs and 36

RBI

s.

19

But the key to the Dodgers’ success was their .365 on-base percentage, which was 11.3 percent better than the .328 league average. Six of the eight regulars posted on-base percentages over .370. Seven of them, Hodges being the exception, walked at least as often as they struck out.

20

As a result the Dodgers did not have to rely on power hitting as much as manufacturing runs by utilizing the bunt, hit-and-run, and base-stealing. The small-ball strategy allowed the team to compile a 98-55 record, earning them another shot at the New York Yankees in the Fall Classic.

21

The Dodgers were a stronger team statistically than the Yanks, but they simply didn’t have luck or fate on their side. In the previous five years Brooklyn’s hopes for that first world championship went down in flames. Twice they lost the pennant in the last inning of the final game. The defeats were legendary, especially the loss in the 1951 playoff to Bobby Thomson and the Giants. On two other occasions, they won the pennant only to lose the Series to the Bronx Bombers. By comparison, the Yankees won all but two American League pennants between 1947 and 1958 and an unprecedented five straight world championships from 1949 to 1953. After those achievements Yankees manager Casey Stengel, who failed to make the Dodgers winners, was hailed as a genius by the baseball establishment. It seemed the Brooks were cursed.