It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War (22 page)

Read It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War Online

Authors: Lynsey Addario

It was a perfect opportunity to start working in Africa and to focus on a story with a strong humanitarian angle. I was getting steady work with the

New York Times

and

Time

, and I had managed to save a little money during my long stints in Iraq, when all my expenses were paid for by the paper. It was the first time in my adult life I wasn’t consumed with anxiety over the next assignment and the next dime, and I could afford to take a risk.

I had no way of knowing then how important Sudan would become to me. I would return for five consecutive years and would establish a deep connection to the country and its people. My work in Africa would change my career, and my life.

• • •

S

OMINI AND

I

MET

up in Ndjamena, the capital of Chad, and flew to Abéché, a Chadian town close to the Sudanese border. Our French military aircraft was manned by two extremely good-looking French pilots, who invited us to sit in the cockpit and watch the stretches of desert beyond the panorama of the windshield. I had never seen endless swaths of unpopulated, virgin land. The pilots showed off for us, tilting their aircraft to the left and right, and I ended up puking into a bag for the entire second half of the flight. So much for being a freshly single, veteran photographer and impressing the good-looking soldiers.

In Abéché we spent the night at a UN guesthouse before traveling by four-wheel drive to the remote village of Bahai, where refugees were arriving in droves from across the border in Darfur. In late 2004, there was little infrastructure at the refugee camps: The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the international aid groups were so overwhelmed by the sudden influx of tens of thousands of refugees that most had not received shelter or food and were accessing water through emergency water bladders set up in the desert by the NGOs.

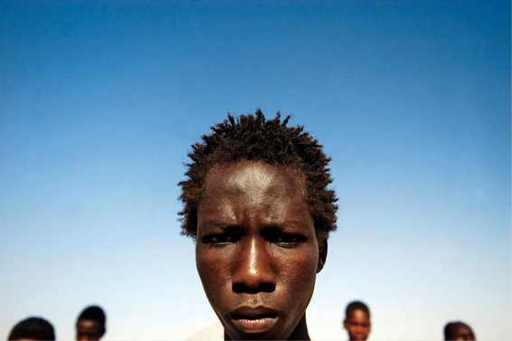

As we traveled to Bahai I realized what a punishing journey it would be for refugees, with nothing but sand from horizon to horizon. I saw makeshift tents populated by malnourished civilians with fresh terror in their eyes. Skeletal villagers who had arrived seconds ago nestled under spindly trees with tattered fabric hung in the branches as sunshade. They were hungry, thirsty, and too listless to beg or move. I instantly reverted to the reserves of my memory for similar images: James Nachtwey’s images from the famine in Somalia, Tom Stoddart’s images from South Sudan, Sebastião Salgado’s workers from around the world, Don McCullin’s images of the Biafra famine. Darfur was not a famine, but it was the first time I had seen people who simply didn’t have food and were so weakened by their escape that they could barely walk.

I moved around the desert camp self-consciously, a white, well-fed woman trudging through their misery. The people understood that I was an international journalist, but I was still trying to figure out how to take pictures of them without compromising their dignity. As much as it would be natural to compare this misery to that in Iraq, it was impossible. Iraq and Darfur were two different worlds, yet my role was always the same: Tread lightly, be respectful, get into the story as deeply as I could without making the subject feel uncomfortable or objectified. I always approached them gingerly, smiling, using their traditional greeting. The Sudanese spoke Arabic in addition to their local languages, so it was familiar to me. “Salaam aleikum,” I would say, and then, “Kef halic? Ana sahafiya.” (How are you? I am a journalist.) “Sura mashi? Mish mushkila?” (Photo OK? No problem?)

And they would nod, or smile back. They never refused.

The crisis in Darfur was a fast-developing story, and the international community had begun throwing around the word “genocide.” Few photographers had shot the refugees at that point. By then I had seen how our devastating photos from Iraq had forced policy makers and citizens to be cognizant of the failures of the invasion. I hoped that heartrending images from Sudan—especially on the front page of the

New York Times

—might motivate the United Nations and NGOs to respond more urgently to this crisis. As the Sudanese government continued to deny wrongdoing in Darfur, photojournalists could create a historical document of truth.

• • •

T

HE

S

UDANESE GOVERNMENT

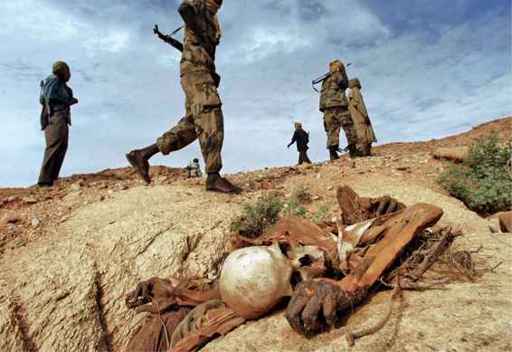

wasn’t issuing journalist visas for Darfur, so the only way for a journalist to cover the situation at the time was to sneak in illegally from Chad. The SLA had almost no financial support and its logistics were minimal, but journalists sometimes crossed the border with them. The SLA’s leaders were wise enough to understand that media coverage might help their cause, so they used their every last resource to accommodate trips into Darfur.

Like most rebels, the SLA used tattered Kalashnikovs. Often a dozen fighters shared one dilapidated truck. For my visit to Darfur, the SLA grouped four foreign journalists together—me, Somini, freelance photographer Jehad Nga, and Jahi Chikwendiu of the

Washington Post

—oblivious of the competition between teams of journalists vying for exclusive stories. It was a hodgepodge of a group. Jahi was a charismatic and talented African American photographer who had traveled extensively around Africa and called all the rebels “my brother,” grinning widely. Jehad stood over six feet tall, weighed about as much as me, and rarely uttered a word.

The plan was to drive to the edge of Chad, then walk a couple miles through the no-man’s-land between Chad and Sudan and meet the rebels in Darfur. We knew we would have to carry everything on our backs while in Darfur, so we minimized our kit, leaving behind lenses, batteries, clothes, shoes, and, not so intelligently, several bottles of water. We set forth on our five-day journey across the Sahel, the southern edge of the Sahara.

The heat was brutal. Even the small amount of weight we each carried seemed too much under the desert sun. Soon after setting out, we came across some nomads with a string of camels who kindly offered to strap our water, tents, and anything else we could manage to the humps of their herd to lessen our load. We formed a little convoy of man and animal, trudging through the sand. Not a single nomad drank even a sip of water over the three-hour walk. I plowed through the first of two bottles I carried. We should have carried more water.

The Sahel was laced with wadis, gullies that filled up during and after the rainy season with fresh streams of muddy water. They flowed like arteries through the desert landscape. We were tempted to drink from the wadis, but they were brown and viscous, sure to induce an immediate case of diarrhea. When we arrived at the edge of the first mini river, chest high and muddy, our improvised guides formed a human chain and passed our things from one side to the other. I stripped off my shoes, sunk my toes into the clay-colored muck, and made my way, holding my passport and cameras high above my head.

Once we reached the other side, a few miles into Sudan’s rebel territory, we met the SLA rebels—a collection of lithe, sinewy young men, most wearing brightly colored turbans and old American basketball jerseys and T-shirts they could have picked up from a Goodwill in Minnesota. The “vehicle” we were promised in Chad turned out to be a pickup stripped of almost everything but the wheels and the frame and sagging with the weight of seventeen rebel fighters. Their clothes, sleeping gear, pots and pans, giant jugs of water, gasoline, and Kalashnikovs formed a mini mountain five feet high above the bed of the truck, and it was all held together by crisscrossing ropes tethered to the sides. They motioned for us to climb on. I wondered how long we could endure the ride, clinging for our dear lives to the shoddy ropes as we plowed through the sand toward emptiness.

I used the pidgin Arabic I’d learned in Iraq to talk with the Sudanese rebels, and Somini tried her French, but we mostly communicated through incoherent attempts at sign language. At night we slept wherever the rebels slept, hoping to find refuge under a beautiful, beefy African tree—rare in the landscape we were traversing. Somini was generous enough to let me share her tent with her; in Chad insects had spit acid on my skin, leaving long, watery blisters up and down my arms by morning. Jahi had brought a single-man tent and set up alongside us. Poor Jehad slept upright in the passenger seat of the truck and was devoured by the mosquitoes.

On our second day we were low on water, and there was no well in sight. We had assumed there would be someplace to buy bottled water in Darfur. We were stupid. There were no proper stores in the villages we passed, and the air was hot and dry like a blow-dryer on our faces and throats. Somini, Jehad, Jahi, and I shared a “food bag,” in which we pooled what we had brought from Chad: pasta, cans of tuna, protein bars, biscuits, and sugary pineapple- and orange-flavored drink mixes. It wasn’t enough food, and we were always hungry and always thirsty. I was convinced we would dehydrate and meet our fate in the middle of the desert, trying to ascertain whether Darfur was a genocide or a civil war.

Every couple of miles the truck would sink into the sand, its wheels spinning, digging deeper into the abyss. Or the truck would simply break down, because it was old and overworked. We then sat for hours as one or two guys fiddled with the motor with a screwdriver or a tool from 1965 while the others splayed out, happy in the sand. They ate out of communal bowls full of

asida

, a grain-based dish that looked like a ball of plain oatmeal. Some would hunt for gazelles—a gourmet lunch—while the others would nap. Miraculously the truck always restarted, but it took us almost three days to travel just twenty miles into northwestern Darfur.