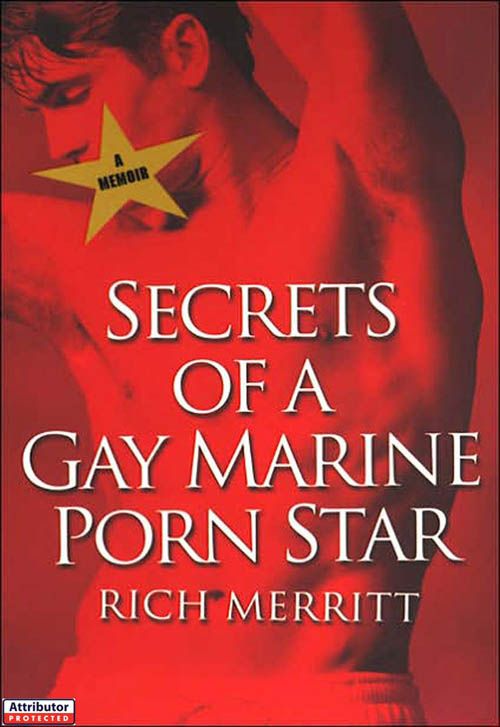

Secrets Of A Gay Marine Porn Star

Read Secrets Of A Gay Marine Porn Star Online

Authors: Rich Merritt

SECRETS OF A GAY MARINE PORN STAR

“Rich Merritt writes an honest, inspiring, sexy, funny, and courageous story. It is filled with insights into military life and the workings of the media, but what truly resonates is the account of one man’s journey to self-acceptance and the welcoming, joyous embrace of gay culture.”

—William J. Mann, author of

All American Boy

“Inspiring, thought-provoking, and brutally honest, Rich Merritt’s story is much more than that of a Marine who found himself at the center of a political firestorm. It is the story of a young man’s coming of age, of the hypocrisy of the gay media and political organizations, and, ultimately, of what it means to come to terms with who you are while being pulled in multiple directions.”

—Michael Thomas Ford, author of

Looking For It

“This is a timely and powerful memoir, an eye-opening survey of wildly incompatible worlds including Bob Jones University, the gay Marine underground, the porn industry, and the circuit party ghetto. At a moment when our country has fallen prey to the lure of various fundamentalisms, this book issues a compelling indictment of what its author calls ‘the internal tyranny of fundamentalist dogma.’

Secrets of a Gay Marine Porn Star

spellbindingly charts a young man’s perilous journey from the iron-clad, killing certainties of his upbringing to adulthoods hard-won self-acceptance and compassion. Rich Merritt writes incisively and, indeed, often quite sexily about a life of closets, confusion and, finally, the great courage of his convictions.”

—Paul Russell, author of

War Against the Animals

and

The Coming Storm

“Rich Merrit’s had an amazing ride, and his memoir rivetingly takes us along on it, tying together his disparate roles—good Christian, porn star, military gay—with saucy wisdom. You couldn’t make this stuff up!”

—Michael Musto,

The Village Voice

“Merritt has written a powerfully honest and compelling story of living two lives. One is of service to his country and one of courageoulsy seeking to come to terms with being a sexual human being.”

—David Mixner, author of

Stranger Among Friends

RICH MERRITT

KENSINGTON BOOKS

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

For “Slim”

Because this is a book about my life, the entire text is an acknowledgment of sorts (albeit with mostly fake names) to the many people who have helped or hindered me along my journey. The book itself, however, would never have become a reality without the influence, encouragement, and patience of a few extraordinary people. Charles Casillo took a scattered bundle of pages and immediately recognized a wild, sad and memorable story waiting to be told. I am eternally in his debt for being my coach, editor, co-conspirator, stenographer, ghostwriter, therapist, fellow outlaw and best of all, my friend. Charles helped me find a writer’s greatest treasure—my voice. I met Charles through Terri Fabris, former editor at Alyson Publications. Terri was the first to detect that I had more “secrets” to tell, and she and Charles prodded me until I told all of them. Hollis Griffin, former publicist at Grove Atlantic, sent me off in Terri’s direction and my dear friend, Seth Levy, a modern messiah, connected me to Hollis.

Charles referred me to the rarest of finds—an agent with a warm and sensitive heart. Mike Hamilburg was instantly as excited about this book as Charles and I were, surprisingly since he is a heterosexual male, a father with young children, not exactly my target demographic. He has given me hope that everyone can connect to my story somehow. Best of all, Mike knew exactly the right editor for this book, sparing my delicate and tender soul the agony of countless rejections. It has been a joy to work with John Scognamiglio and everyone at Kensington Publishing this past year and a half. In this neo-conservative pseudo-morality-driven era we now live in, they have taken a significant risk in putting a book like this into the marketplace. For all of us, I pray that their boldness pays off in droves. Let the backlash begin.

Before this book was ever conceived, Ron “Aunt Ronnie” Schrader said to me, “Girl, what are you doing wasting your time writing novels! Write your own story, it’s WAY more exciting than any fiction!” Aunt Ronnie also led me back to the Lord…the real God, that is. It was Carolyn Carter, my stand-in mom, who helped me see that all love begins with self-love and that the self-hatred of our fundamentalist pasts is the greatest sin of all. Brandon, what can I say? He taught me how to love and his love for me saved my life. Literally. I will never forget my first love and what a lucky bastard I am that it was with someone so wonderful and special.

No one has been more relentless in the futile pursuit of the elusive masculine military mystique than Steven Zeeland. I am proud to be his friend and his loyalty to me has been as unwavering as his love for soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines.

Charles Ching of All Worlds Video went out of his way to provide me with photographs. Rick Ford,

aka

“Dirk Yates” deserves special recognition. He has long been a brave pioneer in the world of gay male entertainment in a nation intent on dictating behavior to other people. Freedom-loving folks everywhere should thank him for his battles on the front line for First Amendment freedom.

I am especially grateful to all of the men and women in the Marine Corps. I suspect that some people will misinterpret my story as a slam against the Corps and some will say that I have brought dishonor to the Marines. Nothing could be further from the truth. I love the Marine Corps, and I have a tremendous amount of respect for all Marines. Maybe if I had it all to do over again, I’d do it differently. But that’s not an option now, so it’s pointless to think about it. What is dishonorable is the way our nation treats gay men and women who wish to serve in the military. All servicemen and women make sacrifices, but gays and lesbians in the military make the biggest sacrifices of all.

I’ve enjoyed the companionship of all my fellow travelers. There are too many to list, but dammit I’m going to try: David, Jim, John, John, Mike, Russ, Kelly, Lisa and Vegas. Bossy. Jack, Charles, Tommy and Keith. Jack, Dominic, Mark, Todd, Cary, Chris, John, Charles, Byron, Eric, Michael, Joe, Amadeus, Filet, Dakota and Buster. Ty, Rich, Jason, Gary, John and everyone else in the Gay Men’s Chorus of Orange County. Bruce, Casey, Tanya, Ashleigh, Michael, Katherine, Eric, Jorge and Danny. USC Law School faculty, staff, students and GLLU. Heather. Brie. Terri and DeeAnn. Tracy and Harris. Kim, Jackie, Katie, Michael, Sasha, Mira, Mark, Kate and Annalyn. Galen and Rob. Amy. Barry, John, Rich, Sony, HT, Andrew, Pixie, John, Martin, Michael Mack, Mick, Diesel, Russ, Streeter, Tommy, Glen, Tony, Forrest, Rob, Alex, Jim, Vu, Tom, Andy, Brandon, Michael and Randy. “Dream” and Bob. Todd and Kevin. Mauricio, Milo, Tim, Alberto, Michelangelo, Mark. Israel. Norah, Graham, Tali, Kyle, Heather. Anne, Paul and Cole. Greg, John, Megan, Scott and Wayne. Oran, Shaun and Russ. “Donna Summers—Sometimes Catered, Sometimes Not.” Icebreakers. Jamie, Rob and Dawn. Many, many more.

Although most of my family will never understand why I wrote this book, they’ll just have to trust me when I say that I love them all very much, just as they are.

Finally, I owe a special thanks to Bob Jones for teaching me that absolute truth exists, and for launching me on my journey to discover it for myself.

Our secrets keep us sick.

—One of my therapists

T

HE

M

ARINE

W

HO

W

AS

A

LSO A

P

ORN

S

TAR

I

didn’t expect the article to be a story about me. I honestly didn’t. I thought it was going to be a story about my friends, about this group of guys and how we all stuck together, and how we always tried to be there for each other.

The

New York Times Magazine

had assigned a young, freelance writer named Jennifer Egan to write about what day-to-day life was like for those of us in the military living under the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. About how we felt trapped in this kind of no man’s land. The article would reveal how we were not necessarily a part of the military community because we were gay—there was always that distinction. Yet we were not completely part of the gay community either, because we were in the military. We were caught in the middle. But at least we had each other. That’s how we all felt and that’s what I hoped the story would convey.

In researching the story Jennifer contacted the Service Members Legal Defense Network (SLDN), an organization out of Washington which provides free legal services for anyone in the military facing an investigation, charges, or any problem with the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. Jennifer asked SLDN for assistance in locating military people who would be willing to talk about their experiences. Since southern California has a heavy concentration of military personnel, Jennifer decided to conduct some interviews in San Diego.

I was an active-duty Marine stationed at Camp Pendleton, just north of San Diego, and had been writing op-ed pieces for the

Navy Times

. I had recently written this one piece which suggested that “Don’t ask, don’t tell” should be repealed. That caught the attention of SLDN. I had also been previously introduced to Tim Carter, the co-chair of the organization. Tim contacted me and said, “We’re going to put a

New York Times

reporter, Jennifer Egan, in touch with you; is that okay?”

I said, “Sure.” I thought it would be great to be part of a story that would reach so many readers.

“This journalist is looking for a model of the military,” Carter added. “A poster child.”

I wasn’t exactly sure she’d find that representation in me but I thought there was a good chance she’d see that image in one of the people I planned to introduce her to. I was aware, however, that a “poster boy” was at least a part of who I was. At that time I had attained the rank of captain and I was a commanding officer, the most sought-after position in the Marine Corps. My assignment just before I became a battery commander had been a general’s aide-de-camp, a very high-profile and demanding position that gave me a lot of connections I could use down the road when it came time for promotions and other selections. So the trustworthy, hardworking, reliable Marine was certainly one role I fit into.

The romantic homosexual in a loving relationship was another. I had already gone through my wild period, or so I thought. By now I had been with my partner, Brandon, for almost three years and I was trying very hard to make a committed relationship work.

But we all go to bed with our secrets. Let’s face it, most of us are many personality types dwelling in one body, showing various sides of ourselves to different people as we see fit. I was aware that the

Times

was not digging for the sordid lives that many of us lead in one way or another. They were looking for the golden boy, the guy you always imagine when you hear about gay men in the military. So I thought,

Fine, I’ll present them with that image of myself.

At the time I did not realize just how expert I was at slipping on different masks. My background had trained me well for projecting whatever image was expected of me. My deep dark secret, the thing that would be considered part of my “sordid” hidden life (and the issue that would set in motion the unfathomable ordeal that would soon follow) was the fact that I had appeared in porn films four years earlier. Eight of them. As hard as it is to believe now, at the time I really didn’t think that my brief fling with the porno industry was pertinent to the story because, as I said, I had no idea the story was going to focus on me. All I kept thinking about was,

Finally someone is going to tell our story—what being gay in the military is like for us.

There was a precondition that the interviewees for the

Times

story were to be anonymous. Jennifer explained that the

New York Times

would not give us fake names, but that we could go by one initial. We could pick whatever letter we wanted. I decided to use my real initial. In the article I would be identified as “R.”

I went down to Jennifer’s hotel in Coronado to pick her up, and she and I bonded instantly. We had rapport. She’s very quiet, somewhat timid, but a genuinely warm, receptive person. Plus, my longtime reserve had me longing to be forthcoming about so many things. I had so much inside of me, all these ideas and emotions bottled up about what living under this policy was like. I started spilling my guts out. Yet, the whole time I was talking to her, in the back of my head was the porn thing. I could almost hear an audible debate going on between my opposing selves. It was as if one part of me was saying, “I’ve been in porno movies.” And the other was saying, “But don’t tell her, because if you do, you won’t be part of the

Times

story.” That was the part that won out.

Soon after our interview, I set up a dinner for Jennifer to meet about twelve of my military friends at a house in San Diego. The fact that she witnessed firsthand how we were a support system for each other is what planted in my head that the story was going to be about all of us. I had no idea how much of the focus of the story would be on me and how much of her article would talk about my friends. I was completely unaware of what Jennifer would use or how I would be portrayed. Apparently that’s pretty common in journalism—the subject or subjects of the story aren’t briefed on the work-in-progress.

Maybe I should have picked up clues. As I’m writing this, things pop into my head: I recall that Jennifer came back a few weeks after the initial interviews and for the first time she brought up the issue of photographs. SLDN hadn’t said anything about pictures. Later, when they found out, I could tell they were upset. Pictures would be too dangerous, they said. But at the beginning, they just said “cover story.” I don’t know how they could have thought this could be a cover story without photographs. But Jennifer asked, “What are we going to do about the pictures?”

Most of the people who had participated in the interview were not willing to have their picture taken, even with their faces hidden. I, on the other hand, said to Jennifer, “You’re going to cover my face in the photo and call me ‘R’ in the article? Then, fine. Of course I want my picture taken.” But only two other guys, another Marine officer and a Navy officer, agreed to a photo session.

A few weeks later photographer Matt Mahurin came out to take the pictures. We spent several hours with him. He took some off-duty photos of Brandon and me a few days later. But his first shots were of the three of us officers in uniform taken in Balboa Park. For the pictures of us in uniform, at one point he posed the three of us in a line, saluting. I instinctively felt it would make a fantastic photo and envisioned it on the cover.

The other Marine officer Matt photographed was my very good friend, who was nicknamed “Bossy.” Bossy and I were both decked out in the full Marine dress blue uniform. Bossy, however, had forgotten his white gloves. Matt wanted a photograph with our gloves on, so I gave one glove to Bossy, put one on myself, and then Matt posed us close together side-by-side in a shot where only our gloved hands were visible.

Matt then said he had to get some solo shots of me, although he didn’t say why. He came up with the idea that I should salute, and that that the salute should cover my face. He lay on the ground and took a shot directly up. I thought he was catching only my chest, shoulders, and head.

A homeless vet walked by our little group in the park. “Cap’n,” he said, “your salute is all fucked up.” He was right. My arm was deliberately canted so that my face would be completely covered. As salutes go, it was all fucked up.

“We know what we’re doing,” Bossy said dismissively. The vet mumbled something about being a retired master sergeant and never having seen such a fucked-up salute on an officer and walked away. We resumed the photo shoot before the sunlight disappeared.

Matt had read a rough draft of the article and during the session someone asked him what the story was about. “Well,” he replied, “the story’s about Rich and his friends.”

That startled me.

Oh my God

, I thought,

this story is about me? An eight-thousand-word article is a

New York Times

cover story about me!

On one hand, it was exhilarating. But now more than ever the porn thing was haunting me. I had an impulse to call Jennifer and tell her not to write about me. Obviously I didn’t give in to that urge. Maybe it was ego. I had spent so much of my early life living up to the expectations of others and here, just maybe, now it was

my turn.

And it was a subject that I was passionate about, something that was pertinent to my life and thousands of others. I knew that it would help a lot of people—I was desperate to be a part of it.

A few weeks before the story appeared, the fact checker called and started asking questions. I was on the phone for almost an hour and I started to feel uneasy. Afterward I made a list of things that she had asked about. By the time I was finished I thought, “I’m toast!” There were key things I had told Jennifer that made me completely identifiable: General’s aide. Commanding Officer. Captain. Southern California. From a Southern religious family. Had done overseas tour. Had been on ship. Initial “R.” It wouldn’t be difficult to connect the dots. Anyone who knew me and read these things, would know I was the “R” in the story.

The magazine was scheduled to come out, so to speak, on Gay Pride Day. I still had six weeks left on active duty after that. They wouldn’t wait for me to be out to publish it because, obviously, the

New York Times

doesn’t change its publication schedule for a personal issue that arises. I felt that I would be safe because I had submitted my resignation already. I knew the Marine Corps would rather just let it slide. They would rather just let me slip quietly out the door rather than make a big issue out of this. Yeah, the

Times

cover story was going to be a big deal, but it would be a much bigger deal if they came after me. I was counting on that.

Two weeks before the article appeared, I was in Los Angeles for an SLDN pool party/fund-raiser. At this party I met a freelance writer named Max Harrold. By now, there was a definite buzz in the air about the upcoming

New York Times Magazine

article. Max approached me, “This sounds really fascinating,” he said. “When do you get out of the Marines?”

I told him that I’d be officially out in the fall. I could almost see the wheels turning in his head. “Can I do a story on you when you get out?” he asked eagerly. “We can reveal your identity and I’m pretty certain I can sell it to

The Advocate

or one of the other magazines.” I liked the idea as long as I was safely out of the Marines. I agreed that as soon as I was officially out of the service, I would give him an interview.

As time grew closer to the date of publication of the

New York Times

story, my immediate concern was that the Marines would find out I was the “R” from the story while I was still in the service. I tried to talk myself out of my fears. I kept telling Brandon, “Oh, there’s nothing to worry about. They don’t say who I am.” But, although I hadn’t seen an advance copy and I had no idea what was going to be in there, I had a nagging feeling the Marines would find out who “R” was.

Saturday, June twenty-seventh fell during Gay Pride weekend in Los Angeles and I knew we’d be able to get an early copy of the Sunday

New York Times

there. As Brandon and I were driving up, I was well aware that it was already on the stands in big cities. I can’t even describe the excitement. The anticipation. The fear. The anxiety. All of that.

We finally got up to LA and, without stopping, went directly to see my friend Tim Carter. The first thing Tim said is, “Rich, you’re finished. You’re history.” He handed me a copy. The first surprise was the cover. There I was saluting—alone! All the while, I had been thinking they were going to use the photo of the three of us standing in a line.

Tim was beside himself. “Look, this is you!” he said immediately. He started talking about General McCorkle, the man I had been the aide to, “You don’t think that he’ll be able to look at this and see that it’s the side of your head?”

I looked at the cover very closely. You couldn’t see my face but you could see everything from my ear back. I thought I was unrecognizable. “No,” I said to Tim. “I don’t think you can tell that this is me. For one thing, I look six feet tall. I’m only five seven.”

The illusion about my height wasn’t the only abnormality in the photograph. At first I didn’t notice the glaring defect. A friend and fellow Marine who was also quoted in the article called me the following day.

“

You’re wearing only one glove!

” He exclaimed. “

What were you thinking?!

” He was right. I hadn’t noticed it, but there I was…a one-gloved Marine. I was out of uniform, the worst mistake a Marine can make. Well, almost.

Fuck,

I thought.

I forgot to get the glove back from Bossy. Besides, I thought Matt was only taking the shot from the chest up!

My ungloved left hand was visible. What was worse, my left thumb wasn’t along my trouser seam as I had been trained for so many years to stand at the “position of attention.” If it had been, my bare hand wouldn’t have been visible. I had been concentrating so hard on covering my face with my right hand, I hadn’t paid attention to my left.

But tonight I didn’t notice the glove issue—I was too focused on the content of the story. I read it quickly and admitted, “Yeah, they’re going to know it’s me.”