It Chooses You (17 page)

Miranda: I just got married about two months ago… I hope we have as many fourth of Julys together.

I did some quick math — in sixty-two years I would be ninety-seven and my husband would be one hundred and five. Our limericks probably wouldn’t rhyme anymore. I turned my attention to a huge collage of pet photos.

Joe: All them animals are gone now, but those are from years ago. The last dogs died in 1982. We had nine of them, and they all died within fifty-one days. Could you believe it? From Christmas Day till the first of February.

Miranda: You had nine dogs at once?

Joe: Yeah, we had twelve dogs when we moved out here, and for the first six, seven years people thought we only had one dog because they were more or less in the house all the time. Now we’ve got cats, but one, Mother wants to take him in tomorrow, I think, and maybe put him away. He’s maybe nineteen years old, and all of a sudden he started going downhill. We feed him about eight times a day, but yet he’s skin and bones now. The vet says that happens sometimes when they get older, because I know he eats. But he’s pretty bad now.

Miranda: What’s his name?

Joe: His name is Snowball, and his picture should be up here someplace. It’s over in those pictures over there — he’s a white cat. And the other one’s in the bedroom with my wife; her name is Silky.

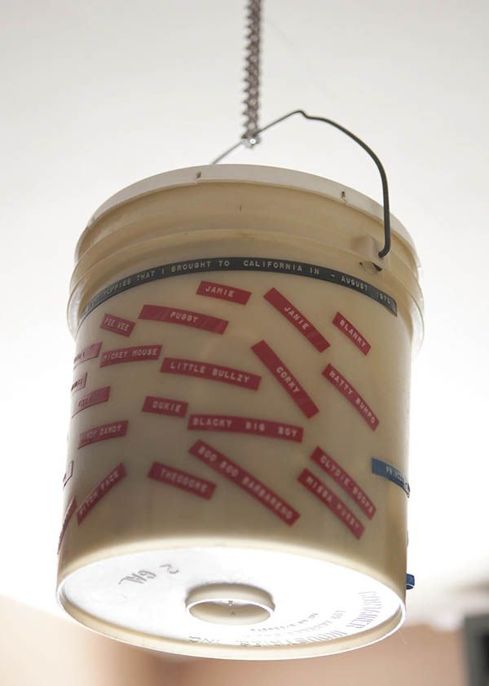

Miranda: What’s in that container hanging from the ceiling?

Joe: Oh, that’s the favorite toys of some of our pets. See, it says, the names on this container are of the eight puppies that i brought to california in august 1970. rosie our outside cat for seventeen years, jannie, ginger, bonnie, huggy bumbum, big fat teddy bear, randy dandy do zo, princess tootsie bell, missapussy, clydie boops, blackie big boy, corky… and so on.

Joe looked misty-eyed as he read the names on the bucket; a rare moment of silence came over him and he glanced around the room as if looking for something else to say. I pointed at a pile of lists.

Miranda: Are these grocery lists?

Joe: Yeah, I shop for seven different widows and one widower — they can’t get out of the house. I’ve got one jacket that I wear when I go to the store. It belonged to a policeman I knew that got shot and killed, and his brother gave me his jacket. He says, “Every time you go to the grocery store I want you to wear it.” Well, I go at least four times a week, at least maybe two hundred times a year, times thirty-five, thirty-six years. I must’ve worn that to the store, oh, three or four thousand times, and my wife has had to repair it. But now it’s almost beyond repair.

Joe wanted to show me the backyard, which was filled with dozens of poky palms that he said were all descended from one tree that he had pulled out of someone’s trash. We wove between the plants to the back wall, which was engraved with names.

Joe: This is where I got most of the dogs and cats buried. I don’t bury them six inches under the ground — I dig a hole seven foot deep, figuring no one will ever take them out, and I keep them close to the wall. I figure if anybody comes in there and puts in a pool, they wouldn’t affect it at all.

Miranda: That’s pretty deep.

Joe: Yeah, I have to have a ladder right next to the hole so I can get out. I can’t even get out of the hole.

Miranda: What’s written in the walls?

Joe: Well, I chiseled the dogs’ and cats’ names there with a chisel and a hammer. There’s names all over — there’s Jilly and Corky and Mittens and Puggy and all.

Miranda: And the hole, is that for a cat that is —

Joe: That’s Snowball’s — gonna have to be put down.

Miranda: Right. So that’s in advance.

Joe was overwhelming, but not like Ron. He was like an obsessive-compulsive angel, working furiously on the side of good. It became harder and harder to remember that I had met him just today and had no responsibility to him, or history with him.

Joe: Maybe this Christmas you can come over, because I put my decorations up about the fifteenth of November and leave them up till the fifteenth of January. So you’re welcome to come anytime. What’d you say your first name is — Mary?

Miranda: Miranda.

Joe: Oh, Miranda.

Miranda: What was your name again?

Joe: Joe.

Miranda: Joe. Right. Well, we don’t want to take up any more of your time. We’ll just get —

Joe: That’s okay, I got time.

When we finally extricated ourselves, we just sat in the car, very quietly, and were oddly tearful. Alfred said something about wanting to be a better boyfriend to his girlfriend. I felt like I wasn’t living thoroughly enough — I was distracted in ways I wouldn’t be if I’d been born in 1929.

And yet the visit was suffused with death. Real death: the graves of all those cats and dogs, the widows he shopped for, and his own death, which he referred to more than once — but matter-of-factly, like it was a deadline that he was trying to get a lot of things done before. I sensed he’d been making his way through his to-do list for eighty-one years, and he was always behind, and this made everything urgent and bright, even now, especially now. How strange to cross paths with someone for the first time right before they were gone.

I called Joe again later that day — I didn’t let myself think very hard about it. I picked up Alfred and the video camera and drove back to the house by the airport. I suggested we reenact our first meeting; I would knock on the door, he would let me in, he would show me the Christmas-card fronts. Get it? Yep. Okay, let’s try it.

An unexpected thing happened when Joe opened the door, and it wasn’t the unexpected thing I now knew to expect. Joe ad-libbed. He told me to watch my step when I came in. He didn’t go straight for the cards — he showed me around a little. He pointed out some things he’d wanted to show me anyway. He hadn’t forgotten about the reenactment — he just had his own agenda. I had to interrupt: “Now I’m going to try to leave, and remember how you sort of wouldn’t let me leave last time?” He nodded. “Do that, don’t let me leave.” I headed for the door. “Stick around,” Joe called out. “I might show you some things you never knew existed.”

We went to the backyard to reenact Joe’s tour of his pet cemetery. “Our cat is named Paw Paw,” I said, thinking Jason could say something like this. Joe looked at me with confusion and I explained there was a cat named Paw Paw in the movie. “Was he named after the lake?” he asked. “No,” I said, and I tried to explain that he wasn’t completely real, even in the movie; he was more a symbol of this couple’s love. He interrupted me. “Because me and my wife met at Lake Paw Paw, sixty-two years ago.”

I drove home with a tape full of scenes that started out as improvisations but consistently careened into reality, becoming little documentaries. Joe could do what I asked, but his own life was so insistent, and so bizarrely relevant, that it overwhelmed every fiction. And I let it.

I thought about his sixty-two years of sweet, filthy cards and something unspooled in my chest. Maybe I had miscalculated what was left of my life. Maybe it wasn’t loose change. Or, actually, the whole thing was loose change, from start to finish — many, many little moments, each holiday, each Valentine, each year unbearably repetitive and yet somehow always new. You could never buy anything with it, you could never cash it in for something more valuable or more whole. It was just all these days, held together only by the fragile memory of one person — or, if you were lucky, two. And because of this, this lack of inherent meaning or value, it was stunning. Like the most intricate, radical piece of art, the kind of art I was always trying to make. It dared to mean nothing and so demanded everything of you.

I imagined Jason meeting Joe and experiencing the light-headed feeling that I was having. I knew I would fail at it, this reenactment; I would make something a little clumsier and less interesting than real life. But it wasn’t the Local Authorities telling me this; it came from higher up, or deeper down, and it came with a smile — a challenging, punky little smile, a dare. I smiled back.