Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (3 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

Leaving Diego Garcia International Airport, Calabresi might have stayed at the Chagos Inn; dined at Diego Burger or surfed the internet at Burgers-n-Bytes; enjoyed a game of golf at a nine-hole course; gone shopping or caught a movie; worked out at the gym or gone bowling; played baseball or basketball, tennis or racquetball; swam in one of several pools or sailed and fished at the local marina; then relaxed with some drinks at one of several clubs and bars. Between 1999 and 2007, the Navy paid a consortium of private firms called DG21 nearly half a billion dollars to keep its troops happy and to otherwise feed, clean, and maintain the base.

The United Kingdom officially controls Diego Garcia and the rest of Chagos as the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). As we will later see, the British created the colony in 1965 using the Queen’s archaic power of royal decree, separating the islands from colonial Mauritius (in violation of the UN’s rules on decolonization) to help enable the expulsion. A secret 1966 agreement signed “under the cover of darkness” without congressional or parliamentary oversight gave the United States the right to build a base on Diego Garcia. While technically the base would be a joint U.S.-U.K. facility, the island would become a major U.S. base and, in many ways,

de facto

U.S. territory. All but a handful of the troops are from the United States. Private companies import cheaper labor from places like the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Mauritius (though until 2006 no Chagossians were hired) to do the laundry, cook the food, and keep the base running. The few British soldiers and functionaries on the atoll spend most of their time raising the Union Jack, keeping an eye on substance abuse as the local police force, and offering authenticity at the local “Brit Club.” Diego

Garcia may be the only place in what remains of the British Empire where cars drive on the right side of the road.

In the years since the last Chagossians were deported in 1973, the base has expanded dramatically. Sold to Congress as an “austere communications facility” (to assuage critics nervous that Diego Garcia represented the start of a military buildup in the Indian Ocean), Diego Garcia saw almost immediate action as a base for reconnaissance planes in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. The base grew steadily throughout the 1970s and expanded even more rapidly after the 1979 revolution in Iran and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan: Under Presidents Carter and Reagan, Diego Garcia saw the “most dramatic buildup of any location since the Vietnam War.” By 1986, the U.S. military had invested $500 million on the island.

13

Most of the construction work was carried out by large private firms like long-time Navy contractor Brown & Root (later Halliburton’s Kellogg Brown & Root).

Today Diego Garcia is home to an amazing array of weaponry and equipment. The lagoon hosts an armada of almost two dozen massive cargo ships “prepositioned” for wartime. Each is almost the size of the Empire State Building. Each is filled to the brim with specially protected tanks, helicopters, ammunition, and fuel ready to be sent off to equip tens of thousands of U.S. troops for up to 30 days of battle.

Closer to shore, the harbor can host an aircraft carrier taskforce, including navy surface vessels and nuclear submarines. The airport and its over two-mile-long runway host billions of dollars worth of B-1, B-2, and B-52 bombers, reconnaissance, cargo, and in-air refueling planes. The island is home to one of four worldwide stations running the Global Positioning System (GPS). There’s a range of other high-tech intelligence and communications equipment, including NASA facilities (the runway is an emergency landing site for the Space Shuttle), an electro-optical deep space surveillance system, a satellite navigation monitoring antenna, an HF-UHF-SHF satellite transmission ground station, and (probably) a subsurface oceanic intelligence station. Nuclear weapons are likely stored on the base.

14

Diego Garcia saw its first major wartime use during the first Gulf War. Just eight days after the U.S. military issued deployment orders in August 1990, eighteen prepositioned ships from Diego Garcia’s lagoon arrived in Saudi Arabia. The ships immediately outfitted a 15,000-troop marine brigade with 123 M-60 battle tanks, 425 heavy weapons, 124 fixed-wing and rotary aircraft, and thirty days’ worth of operational supplies for the annihilation of Iraq’s military that was to come. Weaponry and supplies shipped from the United States took almost a month longer to arrive in Saudi Arabia, proving Diego Garcia’s worth to many military leaders.

15

Since September 11, 2001, the base has assumed even more importance for the military. About 7,000 miles closer to central Asia and the Persian Gulf than major bases in the United States, the island received around 2,000 additional Air Force personnel within weeks of the attacks on northern Virginia and New York. The Air Force built a new thirty-acre housing facility for the newcomers. They named it “Camp Justice.”

Flying from the atoll, B-1 bombers, B-2 “stealth” bombers, and B-52 nuclear-capable bombers dropped more ordnance on Afghanistan than any other flying squadrons in the Afghan war.

16

B-52 bombers alone dropped more than 1.5 million pounds of munitions in carpet bombing that contributed to thousands of Afghan deaths.

17

Leading up to the invasion of Iraq, weaponry and supplies prepositioned in the lagoon were again among the first to arrive at staging areas near Iraq’s borders. The (once) secret 2002 “Downing Street” memorandum showed that U.S. war planners considered basing access on Diego Garcia “critical” to the invasion.

18

Bombers from the island ultimately helped launch the Bush administration’s war overthrowing the Hussein regime and leading to the subsequent deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and thousands of U.S. occupying troops.

In early 2007, as the Bush administration was upping its anti-Iran rhetoric and making signs that it was ready for more attempted conquest, the Defense Department awarded a $31.9 million contract to build a new submarine base on the island. The subs can launch Tomahawk cruise missiles and ferry Navy SEALs for amphibious missions behind enemy lines. At the same time, the military began shipping extra fuel supplies to the atoll for possible wartime use.

Long off-limits to reporters, the Red Cross, and all other international observers and far more secretive than Guantánamo Bay, many have identified the island as a clandestine CIA “black site” for high-profile detainees: Journalist Stephen Grey’s book

Ghost Plane

documented the presence on the island of a CIA-chartered plane used for rendition flights. On two occasions former U.S. Army General Barry McCaffrey publicly named Diego Garcia as a detention facility. A Council of Europe report named the atoll, along with sites in Poland and Romania, as a secret prison.

19

For more than six years U.S. and U.K. officials adamantly denied the allegations. In February 2008, British Foreign Secretary David Miliband announced to Parliament: “Contrary to earlier explicit assurances that Diego Garcia has not been used for rendition flights, recent U.S. investigations have now revealed two occasions, both in 2002, when this had in fact occurred.”

20

A representative for Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said Rice called Miliband to express regret over the “administrative error.” The State

Department’s chief legal adviser said CIA officials were “as confident as they can be” that no other detainees had been held on the island, and CIA Director Michael Hayden continues to deny the existence of a CIA prison on the island. This may be true: Some suspect the United States may hold large numbers of detainees on secret prison ships in Diego Garcia’s lagoon or elsewhere in the waters of Chagos.

21

“It’s the single most important military facility we’ve got,” respected Washington-area military expert John Pike told me. Pike, who runs the website GlobalSecurity.org, explained, “It’s the base from which we control half of Africa and the southern side of Asia, the southern side of Eurasia.” It’s “the facility that at the end of the day gives us some say-so in the Persian Gulf region. If it didn’t exist, it would have to be invented.” The base is critical to controlling not just the oil-rich Gulf but the world, said Pike: “Even if the entire Eastern Hemisphere has drop-kicked us” from every other base on their territory, he explained, the military’s goal is to be able “to run the planet from Guam and Diego Garcia by 2015.”

Before I received an unexpected phone call one day late in the New York City summer of 2001, I’d only vaguely known from my memories of the first Gulf War that the United States had an obscure military base on an island called Diego Garcia. Like most others in the United States, I knew nothing of the Chagossians.

On the phone that day was Michael Tigar, a lawyer and American University law professor. Tigar, I later learned from my father (an attorney), was famously known for having had an offer of a 1966 Supreme Court clerkship revoked at the last moment by Justice William Brennan. The justice had apparently succumbed to right-wing groups angered by what they considered to be Tigar’s radical sympathies from his days at the University of California, Berkeley. As the story goes, Brennan later said it was one of his greatest mistakes. Tigar went on to represent the likes of Angela Davis, Allen Ginsberg, the Washington Post, Texas Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, and Oklahoma City bomber Terry Nichols. In 1999, Tigar ranked third in a vote for “Lawyer of the Century” by the California Lawyers for Criminal Justice, behind only Clarence Darrow and Thurgood Marshall. Recently he had sued Henry Kissinger and other former U.S. officials for supporting assassinations and other human rights abuses carried out by the government of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

As we talked that day, Tigar outlined the story of the Chagossians’ expulsion. He described how for decades the islanders had engaged in

a David-and-Goliath struggle to win the right to return to Chagos and proper compensation.

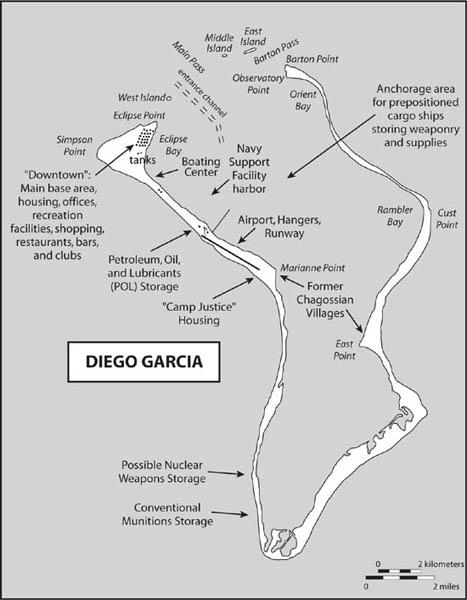

Figure 0.2 Diego Garcia, with base area at left.

In 1978 and 1982 their protests won them small amounts of compensation from the British. Mostly, though, the money went to paying off debts accrued since the expulsion, improving their overall condition little. Lately, they had begun to make some more significant progress. In 1997,

with the help of lawyers in London and Mauritius, an organization called the Chagos Refugees Group, or the CRG, had launched a suit against the British Crown charging that their exile violated U.K. law. One of Nelson Mandela’s former lawyers in battling the apartheid regime, Sir Sydney Kentridge, signed on to the case. And to everyone’s amazement, Tigar said, in November 2000, the British High Court ruled in their favor.

The only problem was the British legal system. The original judgment, Tigar explained, made no award of damages or compensation. And the islanders had no money to charter boats to visit Chagos let alone to resettle and reconstruct their shattered societies. So the people had just filed a second suit against the Crown for compensation and money to finance a return.

Through a relationship with Sivarkumen “Robin” Mardemooto, a former student of Tigar’s who happened to be the islanders’ Mauritian lawyer, the CRG had asked Tigar to explore launching another suit in the United States. Working with law students in his American University legal clinic, Tigar said he was preparing to file a class action lawsuit in Federal District Court. Among the defendants they would name in the suit would be the United States Government, government officials who participated in the expulsion, including former Secretaries of Defense Robert McNamara and Donald Rumsfeld (for his first stint, in the Ford administration), and companies that assisted in the base’s construction, including Halliburton subsidiary Brown & Root.

Tigar said they were going to charge the defendants with harms including forced relocation, cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, and genocide. They would ask the Court to grant the right of return, award compensation, and order an end to employment discrimination that had barred Chagossians from working on the base as civilian personnel.

As I was still absorbing the tale, Tigar said his team was looking for an anthropology or sociology graduate student to conduct some research for the suit. Troubled by the story and amazed by the opportunity, I quickly agreed.

Over the next six-plus years, together with colleagues Philip Harvey and Wojciech Sokolowski from Rutgers University School of Law and Johns Hopkins University, I conducted three pieces of research: Analyzing if, given contemporary understandings of the “indigenous peoples” concept, the Chagossians should be considered one (I found that they should and that other indigenous groups recognize them as such); documenting how Chagossians’ lives have been harmed as a result of their displacement; and calculating the compensation due as a result of some of those damages.

22