Island of Saints (2 page)

Inside the can, dank and mildewed, was what I determined to be an old chamoisâonce soft leather now stiffened by age and the rusty dampness in which it had been imprisoned. Pulling the leather free from the can, I saw that it had, at one time, been carefully folded. Now, though, it was shrunken somewhat, blackened by mold and almost hard on its edges like a big, ugly potholder that someone had starched.

The leather folds came apart easily in my hands, and as they did, a button fell out and onto the sand at my knees. A silver button. Though somewhat tarnished, the face of the button was beautifully etched with an anchor. From its back extended a single loop surrounded by letters so tiny that I was unable to make out anything more than a

K

, an

R

, and on down the line of script, what I thought might be an

A

.

Placing the button on the kitchen porch behind me, I tugged harder at the leather from which it had come and tore a piece completely off. Three more buttons, identical to the first, along with a ring, fell into the sand. The ring was also silver, a bit more discolored than the buttons, and had as its center point an eagle surrounded by a wreath. The ring also had lettersâthese much largerâwhich ran the entire outside circumference of the circle. I read the words aloud: “Wir Fahren Gegen Engelland.”

Not being able to translate or even identify the language, I set the ring aside with the buttons and continued to peel apart the crusty leather. With the final layer laid open, I slowly set the chamois on the sand and gazed openmouthed at what it held. There were four more buttons, making a total of eight, a silver anchor badge about 2 inches tall by 1 1.2 inches wide, some kind of black-and-silver medal with a bit of red, black, and white ribbon attached, and three, only slightly water-damaged, black-and-white photographs.

The first photograph was a simple head and upper body shot of a man in military attire. I didn't recognize the uniform, but saw immediately that the buttons in the picture were the same ones I now had in my possession. In fact, I counted them. Eight silver anchor buttons in the photo . . . and eight on my porch. I really couldn't tell if the man in the picture was twenty or forty, and in that way, he reminded me of old pictures I have seen of college kids in the nineteen thirties or forties. They all looked years older than they actually were.

The man was not smiling. It was as if he was not entirely comfortable with the idea of having a photograph made. He was not thin or fat, though “thick” might have been an accurate description of his body type. The same eagle that appeared on the ring was also on display on the right breast of his uniform jacket and the top of an odd, beret-type cap. Stitched in large, Gothic script along the lower brim of the cap was the word

Kriegsmarine

.

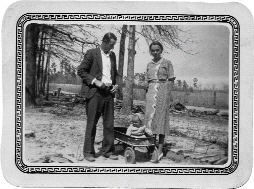

The second photograph was smaller and had a decorative black border framing the print. In it were three figures: a young woman in what struck me as the best dress she owned, a man in a suit and white shirt with no tie, and a baby in a wagon between them. Whether the child was a boy or girl, I couldn't tell. Though the woman looked directly (fearfully?) into the camera, the man's attention was focused toward the child, causing his face to appear in profile. I wasn't certain, but I thought that maybe he was the same uniformed man in the previous photograph.

It was the third photograph, in addition to the ribboned medal, that had my attention. The black-and-silver military decoration was cast in the shape of a cross. At the bottom leg of the cross was a date, 1939, and in its center a more familiar symbol. I blinked as I touched it with my finger and shivered, whether from the January chill or something unseen, I didn't know.

Quickly I looked again to the last photograph. Men on a boat of some sort . . . lined up as if for inspection. On the right corner of the front line, yes, there was the uniformed man from the first picture. Four officers in highly decorated military overcoats were in the foreground of the shot. Three wore dark clothing with what I imagined to be gold or silver trim. The fourth man, to the far left of the photograph, was dressed immaculately in an outfit cut in the same design, but of a paler material. It was this man whose face I recognized. This was the man for whom the symbol on the medal had been created. But why on earth was a picture of Adolf Hitler buried in my backyard?

A WEEK LATER, I WAS STILL NO CLOSER TO ANSWERING MY question. Where had this stuff come from? At least the Internet, with its various search engines, had begun to fill in some of the blanks about what the actual pieces were. And the swastika embossed on the medal gave me some idea of what I might find.

After rushing inside and fanning out the items on the kitchen table for my astonished wife, I retreated to my office and cranked up the computer. The first word I searched was

Kriegsmarine,

the script on the man's hat in the first picture. I quickly found that it was the name of the German navy controlled by the Nazi regime until 1945. Previously titled the Reichsmarine, the Kriegsmarine was formed in May of 1935 after Germany passed the “Law for the Reconstruction of the National Defense Force.” This law brought back into existence a German military presence that had been essentially banned by the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War I.

I next typed in

Kriegsmarine buttons

and was instantly rewarded. There, on my computer screen, was an enlargement, front and back view, of a button exactly like the eight in my possession. The front of the button proudly displayed the anchor while the magnification of the back side clearly revealed the word

Kriegsmarine

stamped in a semicircle. Remembering the letters I had barely made out on the back of the first button I found, I dug an old 8X photographer's loupe out of my desk and looked at the back of one of the actual buttons. There it was, the same semicircular engraving of the same word that stared back at me from the computer.

As I moved my eye from the magnification device, I noticed that the photographer's loupeâa small plastic piece with the brand name Lupeâhad an engraving of its own. “Made in Germany,” it said. If it hadn't been so weird, I would have laughed out loud.

The medalâeasy to findâwas an Iron Cross. First instituted by King Friedrich of Prussia in 1813, it was adopted as a piece of political imagery by Adolf Hitler during the opening hours of World War II and became the most recognizable decoration to be won by a member of the German military. The Iron Cross was rewarded for bravery in the face of the enemy. The actual medal itself was seldom worn, but often carried. An Iron Cross recipient usually displayed only the brightly colored ribbon by running it out the top right buttonhole of his jacket. In the first photograph, I could see that very piece of red, white, and black cloth featured prominently on the Kriegsmariner's uniform.

Next, I began a frustrating search for the

silver anchor

badge

by typing in those exact words. After trying

German

silver anchor badge, German silver rope anchor badge,

and

German Navy silver rope anchor badge

with no luck, I substituted the words

pin

and

medal

for

badge, Nazi

for

German, Kriegsmarine

for

Navy,

and every combination of those terms I could concoct, with the same results. Nothing.