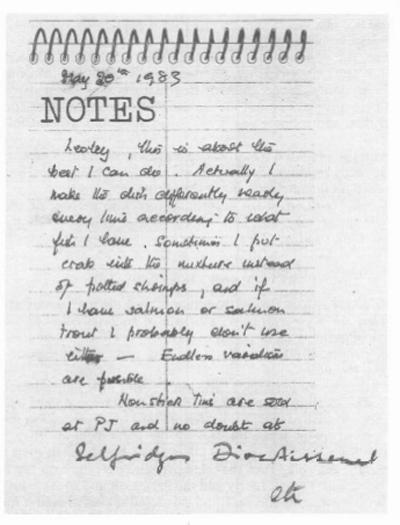

Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (27 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

Chill well in fridge and taste again for seasonings. Have ready a 1.2-litre (2-pint) non-stick loaf tin, brushed with oil. Prepare foil for a cover, also oiled on the side to go over the fish. Pierce a few holes in this prepared cover, using a skewer. (The holes are to allow steam to escape.)

Fill the tin with the fish mixture (but leaving a little space for it to rise), place in a roasting tin three-quarters filled with water, put the foil cover over the fish, if possible doming it up a little so it doesn’t fit too closely.

Consign to oven (170°C/325°F/gas mark 3), lower centre, and cook for approximately 1½–1¾ hours. Test by raising the foil cover, touching top of fish loaf. If just firm, it should be done.

If it is to be eaten hot, leave for a few minutes in the roasting tin in water before turning out. If it is to be eaten cold, take it out of the roasting tin, and leave until wanted, but not in the fridge. When the loaf is to be served, put the tin in hot water for a few minutes. It should then turn out perfectly easily.

If to be eaten cold, have a simple mayonnaise with it, or a sauce verte, or the vinaigrette with a soft-boiled egg and lots of parsley from page 122 of

French Provincial Cooking

. If to be eaten hot, I make a sauce of the rest of the stock, much reduced, with the

addition of cream, some anis or other such, and perhaps a few chopped buttered shrimps.

Unpublished, 20 May 1983

Lesley was Lesley O’Malley who lived in the basement flat of Elizabeth’s house for many years.

JN

PRAWN AND MELON COCKTAIL

125 g (4 oz) peeled prawns, half a small honeydew melon, 150 ml (5 fl oz) each of yogurt and single cream, 2 teaspoonsful each of olive oil and tarragon vinegar, seasonings of ground ginger or turmeric, salt, sugar, and freshly milled pepper; chives, mint, or parsley. Ample helpings for 4.

Peel the melon and cut the flesh into small cubes. Mix the yogurt and cream together, add the oil and vinegar and seasonings – the amount of ginger or turmeric you use is a matter of taste, so it’s best to start with not more than half a teaspoonful of either and then add more if you want – and about 2 teaspoonsful of sugar.

Mix the prepared melon and the prawns with this sauce, and as it needs time for the flavours to blend and to mature, leave, covered, in the refrigerator for several hours.

Finally taste again for seasoning, turn into glasses, or small bowls for serving, and add a sprinkling of chives, or chopped fresh mint, parsley, or fennel to each.

LETTUCE AND ANCHOVY SALAD

This recipe is Mrs Benny Goodman’s, and the ingredients are a cos lettuce, a 50 g (approx. 2 oz) tin of anchovy fillets in oil, a clove of garlic, 3 tablespoons of olive oil, the juice of one lemon, salt, pepper, the raw yolk of one egg, and one tablespoon of grated Parmesan.

First crush the garlic clove and put it with a little salt and freshly milled pepper into a cup with the olive oil and leave to stand a while.

Pull the washed and drained lettuce into small pieces. Put them in a bowl, pour in the oil, leaving the garlic behind. Then the lemon juice. Add the anchovy fillets plus a little of their own oil. Next, the egg yolk. Turn the salad over and over until the egg has blended with the oil. Lastly add the Parmesan and mix again.

With bread and cheese, I find this salad makes almost a meal in itself for it is both refreshing and satisfying.

Recipes from

Sunday Dispatch

, 1950s

Two Cooks

Angela was Maltese and a born cook; she was scatter-brained and excitable, she never could be made to understand that my sister, for whom she worked, did not appreciate the smell of beef dripping being rendered down permeating the house from morning till night, and she seldom remembered that the English take it for granted that potatoes are served with every meal and so do not include them in the orders for the day; meal-times were frequently attended by the drama of ‘Where are the potatoes, Angela?’, ‘Oh, Madam, I forgot’.

Angela had spent her life working for naval and military families in the island of Malta, and it was something of a mystery as to how she had retained a sincere and undimmed enthusiasm for the art of cooking. Always delighted to try out a new recipe, she usually succeeded brilliantly; occasionally there was a disastrous flop, usually due to her erratic reading of instructions, ‘Perhaps

you didn’t beat the whites of egg enough, Angela?’ ‘Whites of egg? Oh Madam, I never noticed.’ In those days food was absurdly cheap in Malta, drink was untaxed, and entertaining was easy and immense fun. Marketing was carried on with an oriental approach to the delights of haggling and the triumphs of carrying off a melon a penny cheaper than the original price. In the market one could buy ready boned quails for about sixpence each, chickens could be bought by the leg or the wing, you could even buy half a pigeon if you pleased; there was a prodigal supply of fruits and vegetables grown on the neighbouring island of Gozo; the local oranges were sweet and delicious, there were figs, grapes and exquisite wild strawberries.

One of Angela’s triumphs was small, sweet melons, one for each person, stuffed with wild strawberries and peeled white grapes, flavoured with maraschino. As I have said, she was a born cook, otherwise how could she have known the secret of that dish of Marcel Boulestin’s which has poached eggs in the middle of an airy cheese soufflé mixture – she cooked it to perfection, and never were the poached eggs too hard or the soufflé undercooked. She made milk bread and drop scones for tea which would have made a Scotch cook look foolish.

Angela gave me my first cooking lessons and to her I owe the initial understanding that to a good cook such drawbacks as tough meat and bony old hens are of little account; they existed as a challenge to Angela’s pride and ingenuity. My sister’s table was probably the only one in Malta where the Army ration, consisting of a hunk of beef of no recognizable origin, was not hopefully presented as the Sunday roast, for Angela made good use of the crude local wine for rich stews in the Italian manner. Elderly veal was spread with mushroom stuffing, sandwiched between slices of ham and cooked in paper; stringy birds emerged as creamy soufflés and mousses.

Angela’s passion for a gossip sometimes led to trouble; the day when, recklessly disregarding my sister’s repeated instructions about the cat, she went out leaving the kitchen door open and the quails for dinner exposed on the kitchen table, was a memorable one for us all. We had an honoured and greedy guest coming to dinner, and one of his favourite dishes was Angela’s way of doing quails, boned and stuffed with sweet corn and wrapped in bacon. By the time that Angela returned from her chat with the next door cook the cat had got three or four of the quails. Piercing wails

rent the air, the market was closed, the council that followed was one of desperation. When dinner time came and the unfortunate member of the family who had been chosen as a sacrifice (‘Isn’t it a bore, I’m on a diet and can’t eat quails’) was handed his eggs, Angela gave the whole show away by winking, nudging, and finally quaking with laughter.

My sister brought Angela home to England and for some time she was blissfully happy in a series of different houses in the neighbourhood of Salisbury Plain. She seemed to have reached the pinnacle of human happiness in that damp and clammy atmosphere; she thought the little red bungalows on the road to Andover the most beautiful houses in the world and she continued to cook like an angel. On English mutton and most un-Mediterranean vegetables her talent thrived. Alas, she had never been a methodical girl, and I think in the end it was the orderly life of an English village which got her down. You cannot haggle with a village grocer, and she began to pine for the shouting and the noise and the disorder of Valetta’s market, the incessant gossip, and the fun of preparing immense quantities of food for the parties which had been an almost everyday occurrence in Malta; the deep nostalgia of every true Maltese for their little island overwhelmed her, and in the end she went back, leaving us all bereft. If she is cooking her lovely food and losing the shopping list and leaving the door open for the cat for some English family still, I hope they appreciate their good fortune.

Kyriakou was a Greek from the Dodecanese island of Simi. He was a sponge-fisher and he had escaped twice from the Italians, for whom he had a boundless contempt. When they declared war he had sailed his boat to Mersa Matruh, and when Mersa Matruh was captured he sank his boat in the harbour rather than let the Italians get it, and escaped with the British Navy, carrying with him a sack of electrical equipment he had looted from an Italian store. How he came to be a cook general in our absurdly grandiose Alexandria flat is no longer very clear, and, devoted and charming as he was, a dedicated cook I cannot claim him to have been. He was not entirely of this world, perhaps it was being so much under the sea that made him so dreamy when he was on land. He would sweep the carpet with his gaze fixed on the ceiling, as if he expected any minute to swim to the surface.

The Greeks are the most democratic people in the world and a

Greek servant is in every sense a member of the family; the money spent on housekeeping they regard as their own, and every detail of expenditure is discussed with the same passion which they apply to politics. Together, conversing in unlikely French and fantastic Greek, Kyriakou and I went shopping. It was a time when supplies of Greek olive oil, cheap Cyprus and Italian wines, and imported cheeses were still plentiful, but prices were rising and we knew that soon there would be no more.

Kyriakou’s grief as the cost of a bottle of olive oil crept up from ten piastres to twenty, and finally, giving up all pretence, leapt to eighty, was tragic to watch, and he often had to be consoled with a stiff drink of

ouzou

in the market after spending my money in this reckless fashion. The rising cost of living was considerably augmented by the alarming quantity of breakages in our hideous but lavishly appointed flat. This turned out to be due to the fact that poor Kyriakou, already affected by the disease which finally gets all deep sea divers, would sometimes have a spasm of terrible pain in his right arm, most often when he was carrying a laden tray…

Even this, however, did not account for the number of teapots which he managed to get through in a few weeks; going into the kitchen one day at tea time I found him in the act of putting the teapot, in which there was half a pound of tea and a little cold water, straight on to the gas.

As a ladies’ maid Kyriakou made stupendous efforts, and would tiptoe into my room in the morning in the most elaborate manner, only to drop the tray on the floor with a tremendous crash. Sometimes his housekeeper’s pride got the better of him, and there would be a faraway look on his face as he brought in my morning coffee. With a happy smile he would empty the contents of a shopping basket on to my bed, ‘Fresco, Madame, Fresco’, he would coo; fresh was an understatement, for these were live fish, prawns and crabs and crayfish, slithering and gangling across my eiderdown at seven o’clock in the morning.

We were working erratic hours in Government jobs, and Kyriakou took much of the responsibility for our social activities into his own hands; our friends were his friends, so he would telephone those he liked best and inform them there was a good dinner on that night; not unnaturally the people he favoured were usually Greek-speaking or connected in some way with the Greek cause, so it happened that now and again the chromium and mirror bar,

the road-house splendour of our flat took on the atmosphere of a

taverna

. Kyriakou would sit and drink with us, pouring out the drinks and fetching clean glasses with that grace of a host which is instinctive to every Greek ever born.

One day Kyriakou had news that his wife and children, left behind in Simi, had escaped to Palestine, and he intended to celebrate, he said, by giving a party for us and our friends. Nothing would stop him and we were not allowed to buy a single bottle of wine or contribute in any way to the expense. When a Greek sets out to give a party there is no cheese-paring. Where he went to do his marketing that day I never discovered, because when I asked him he giggled coyly and disclosed nothing, but I suspect that some of it at any rate was an underwater affair, for he returned home with a bucket of shell-fish the like of which had never before been seen in Alexandria; from this he concocted a pilaff which would have made a Spanish paella seem positively penny plain. It was a fish dinner, for as well as the pilaff there were mountains of fried fish (in Greece they like fried fish cold) with a great basin of

skordalia

, the Greek garlic sauce, and the masterpiece of the evening was an octopus stew. With passionate concentration he prepared it, and I watched him build up in a deep pot a bed of branches of thyme on which to lay a huge quantity of onions, tomatoes, garlic, bay leaves and olives, and then the octopus. Gently he poured red wine over his carefully constructed edifice, stirred in the ink from the fish, and left his covered pot to simmer the rest of the afternoon.