Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (23 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

Among the less unamiable characteristics of the Duke of Newcastle, Verral’s original employer and patron, were, according to Walpole, extravagance and love of ostentatious entertainment. His reputation had evidently reflected upon his cook, for in his book Verral is at some pains to vindicate French cooking in general and his former master, Clouet, in particular from charges of wastefulness. The gossips of the period were fond of spreading tales about the arrogance and extravagance of the French cooks employed by English noblemen. The reduction of a whole ham into one small phial of essence or of twenty-two partridges into a sauce for a brace was, according to tattle, common practice; cooks would think nothing of demanding that dining-room doors be widened and ceilings heightened to allow for the passage of

pièces montées

; such stories, Verral says firmly, ‘were always beyond the belief of any sensible person. Much has been said of his [M. Clouet’s] extravagance… but I beg pardon for saying it, he was not that at all… that he was an honest man I verily believe… he was of a temper so affable and agreeable, as to make everybody happy about him.’

Now this charmer had already, when Verral wrote his book, left the service of Newcastle and, returning to France, entered that of the Marshal Duke de Richelieu, he who in 1756 commanded the French forces besieging the British at Port Mahon in Minorca, and whose cook, it is said, brought back to Paris the secret of mayonnaise sauce. Was Clouet that cook? And was Newcastle, a man in a constant fret over trivialities, exasperated that his famous cook should have defaulted to his victorious enemy?

That Clouet was at any rate an intelligent, enlightened and most meticulous cook one can see from the notes and recipes which Verral records as being those of his teacher. From him Verral learned to cook vegetables such as asparagus and French beans only to ‘a crispness and yellow’ and to serve them ‘as [the French] do many other vegetables, for a hot sallet’. He learned to make ‘a better soup with two pounds of meat, and such garden

things as I liked, than is made of eight pound for the tables of most of our gentry and all for want of better knowing the uses of roots and other vegetables’; he learned not to boil the meat to rags as was the common practice and ‘makes the broth both thick and grouty – and hurts the meat that thousands of families would leap mast-high at’; he noted that M. Clouet never made use of powerful herbs such as ‘thyme, marjoram or savory in any of his soups or sauces, except in some few made dishes’ and that in roasting a loin of veal which had been marinated overnight in milk flavoured with onion, bay leaves, shallots, salt, pepper and coriander seeds Clouet would cover the meat with buttered paper but would not have it basted with the marinade, ‘never, nor with anything else’.

At a time when a tremendous quantity of materials was wasted on decoration and garnish, Verral obviously had a great feeling for the proper appearance of his dishes; of that chicken fricassee of which he was so proud he says that anyone can make a fricassee which tastes well, but it must be a good cook to make it look well; ‘and for the goodness of this dish half depends upon its decent appearance’. Of a Julienne soup, ‘you may fling in a handful or two of green pease, but very young, for old ones will thicken your soup, and make it have a bad look’, and of a hare cake you are not ‘so to smother it with garnish but every one at table may see what it is’.

The spirit of Verral was certainly not presiding over the dressing of the smoked trout I ate last time I lunched at the White Hart. Fairly festooned with sallet stuff it was, watercress and lettuce, tomatoes and cucumber, and the fish itself diminished nearly to vanishing point. But then at the White Hart today nobody has so much as heard of Clouet or of Verral; if they had they might (since the inn is French-owned) make a bit of capital out of its past associations (

‘le White Hart, son ambiance historique, ses salles fleuries, son rôti de veau à la broche à la façon du bon maître Clouet, ses primeurs du Sussex, son parking’

), hang pictures of the Pelham family and their cooks in the bar, revive the Shoreham scallop industry, keep crayfish in the nearest dewpond on the Downs and cook their sheep

aux aromates du pays

and their hams in the local cider (Merrydown, what else?). I’d be all for it myself, so long as the goings-on didn’t upset the waitresses; for what is an ancient English country-town coaching inn without a waitress to look you straight in the eye and tell you that ‘you’ll

take your coffee in the lounge, now, won’t you, that’s right, make yourselves comfortable’?

Spectator’s Choice

, 1967

Edible Maccheroni

During the 1914 war Norman Douglas was staying in Rome and recounts (in

Alone

) how he goes in search of ‘edible maccheroni – those that were made in the Golden Age out of pre-wartime flour’. Eventually, acting upon a hint from a friend, he finds them at Soriano, a village lying on the slope of an immense old volcano. The surroundings were sombre, the weather stifling, but ‘those macaroni – they atoned for everything… the right kind at last, of lily-like candour and unmistakably authentic…’

To those who have not experienced pasta at its best, or who have never acquired a taste for it, Norman Douglas’s hankering after the right kind might seem somewhat perverse. But that description – ‘lily-like candour’ explains a good deal. It would be hard to find better chosen words in which to convey the extraordinary charm of those pale, creamy, shining coils of pasta filling a big deep soup plate, in the centre a little oasis of dark aromatic meat sauce, crowned with a lump of butter almost whiter than the macaroni and just beginning to melt.

Whether or not your macaroni, spaghetti, noodles or any other variety of commercially produced pasta has the right attributes depends, as Norman Douglas was naturally aware, even more upon the flour used in its manufacture than upon careful cooking. The most satisfactory flour is that milled from a variety of wheat called Durum. As its name implies this is a hard wheat yielding a flour which, while unsatisfactory for bread-making, imparts those qualities to pasta products which enable them to retain their firmness when subjected to the drying process and their shape when they are cooked. Softer flours, while adequate for the kind of pasta freshly made at home and cooked the same day, are inferior for the manufactured variety because they will not dry evenly, the pasta made from them will splinter, and when cooked will disintegrate and turn to a mush. So, far from presenting that lively and lily-like candour of appearance they will be grey, sticky, and dead looking.

The water used in the manufacture of pasta dough is also said to play an important part in the quality of the finished product, and that made in the Naples district is claimed to owe its superiority to some constituent of the water in the neighbourhood. However, there are flourishing pasta industries in other parts of Italy, notably in Parma and Bologna, and it is doubtful if any but a most expert connoisseur would be able to detect the difference between, say, the spaghetti made by the Neapolitan firm of Buitoni and that of Barilla or Braibanti of Parma.

First-class imported Italian pasta products sold in packets bear the information that they are made from

‘Pura semola di grano duro’

which means that the flour used, like that of the English products, is milled from the cleaned endosperm or heart of the

Durum wheat grain, of which a certain quantity is grown in southern Italy, although it is not always the amber variety. The words

semola

and

semolina

used in connection with spaghetti and macaroni imply that the grain is treated in a particular way so that only the finest and most nutritious part, the cream, in fact, of the wheat, very finely sieved, is used.

The best of those kinds of pasta in which eggs are an ingredient are made from the same flour; in Italian egg noodles, tagliatelle and similar products, five eggs to the 1 kg (2 lb) dough are the standard proportions.

Few English shops would find it worthwhile to stock all the varieties such as bows and butterflies, shells, knots and wheels, melon seeds, stars, ox-eyes and wolf-eyes, rings, ribbed tubes and smooth tubes, cannelloni, little hats, marguerites, beads, miniature mushrooms, quills and horse’s teeth, green lasagne and tagliatelle, twists and twirls and whirls and all the other ingenious inventions which turn an Italian pasta shop into a place of such entrancing fantasy. And incidentally, where all these different shapes and sizes are concerned, it is difficult to give precise definitions, because the names vary both according to regional tradition and to the individual fancy of the producer, so that one particular type may have two, or three or more names. Equally two or three varieties may go by the same name in different districts.

SPAGHETTI ALLA BOLOGNESE

Possibly this is the best known of all Italian pasta dishes but recipes vary very much, and it would be a mistake to suppose that every dish bearing this name, even in reputable Italian restaurants, is cooked as it should be.

Allow 90–125 g (3–4 oz) of long spaghetti per person. For 250–280 g (8–9 oz) bring 4.5 litres (8 pints) of water, plus 2 tablespoons of salt, to a fast boil. Put in your spaghetti unbroken. Within a few seconds it will coil down into the pan. Bring the water back to the boil as fast as possible. Cook steadily for 10–12 minutes. During this time the spaghetti should grow, or swell, to twice or even three times its original volume. Stir once or twice with a wooden fork, just to make sure that no pieces are sticking to the pan. Take a little piece out and taste it. When it is tender, but still firm to the touch, with an almost imperceptible white

core in the centre, it is done. Drain it in a colander. Have ready a heated dish, in which you have warmed a little olive oil or butter. In this turn your spaghetti over and over for a few seconds, rather as if you were mixing a salad. If possible, keep the dish on a table heater while this is being done.

Pile your hot sauce (recipe below) in the centre. On top put a lump of butter. Have ready your hot plates, soup plates for preference, and keep your dish on the heater while the spaghetti is served.

The sauce is made as follows.

RAGU BOLOGNESE

This is the sauce for Spaghetti Bolognese as it is made in Bologna, at the restaurant of Zia Nerina, now in the Piazza Galileo. I have not visited this restaurant since Zia Nerina moved into her new premises, but I fancy it is unlikely that any amount of success could spoil her delicious cooking.

For 4 people the ingredients are 180 g (6 oz) of good quality lean minced raw beef, 90 g (3 oz) of chicken livers, 60 g (2 oz) of uncooked ham or gammon, a carrot, an onion, a little piece of celery, 2 teaspoons of concentrated tomato purée, 1 small glass of white wine and 2 of beef stock or water, seasonings of salt, pepper and nutmeg, about 15 g (½ oz) of butter.

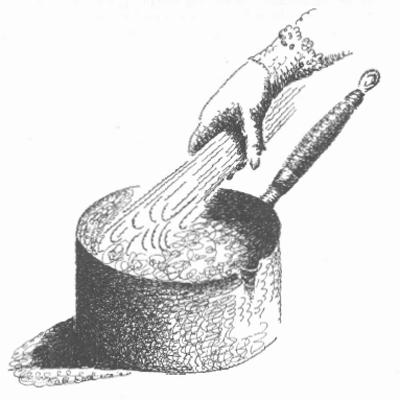

Heat the butter in a small saucepan, add the chopped ham or gammon and when the fat starts to run put in the finely chopped onion, carrot and celery. When they have browned a little add the minced beef, stirring it round so that it all browns evenly; next stir in the chopped chicken livers, then the tomato purée, then add the wine. Let this bubble a few seconds, add the seasonings and the stock or water. Cover the pan. Simmer very gently for 30–40 minutes. Sometimes Bolognese cooks add a cupful of cream before serving, which makes a thicker and richer sauce.

TAGLIATELLE AL MASCARPONE

Mascarpone is a pure, double cream cheese made in northern Italy and sometimes eaten with sugar and strawberries in the same way as the French Crémets and Coeur à la Crème. We have several varieties of double cream cheese here. It makes a most delicious sauce for pasta. The ordinary milk curd cheese now usually sold

as cottage cheese can also be used for a pasta sauce, but the double cream variety produces a dish altogether more subtle.

Tagliatelle are narrow ribbon noodles (the green ones are particularly attractive for this dish because of the contrast of the green pasta with the cream sauce), but one or other variety of small pasta such as little shells, pennine (small quills) and so on can equally be used.

The tagliatelle will take about the same time to cook as spaghetti, 10–12 minutes. Some of the other shapes are much harder, and may take as long as 20 minutes, and although they are small, need just as large a proportion of water for the cooking.

The sauce is prepared as follows: in your serving dish melt a lump of butter and, for three or four people 125–180 g (4–6 oz) of double cream cheese. It must just gently heat, not boil. Into this mixture put your cooked and drained pasta. Turn it round and round, adding two or three tablespoonfuls of grated Parmesan. Add a dozen or so shelled and roughly chopped walnuts. Serve more grated cheese separately.

This is an exquisite dish when well prepared, but it is filling and rich, so a little goes a long way.

SALSA ALLA MARINARA

When pasta is served with a sauce based on a certain quantity of olive oil it is not always considered necessary to serve cheese as well. Some Italians, indeed, consider it absurd to mix cheese and oil; either ingredient, they say, provides, with the pasta, sufficient nourishment to make a balanced dish.