Is Journalism Worth Dying For?: Final Dispatches (37 page)

Read Is Journalism Worth Dying For?: Final Dispatches Online

Authors: Anna Politkovskaya,Arch Tait

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union

On the flight to Tura, where a small delegation from

Novaya gazeta

unveiled a monument at the geographical centre of Russia, December 2000

Vnukovo Airport, Moscow, February 2001, returning after her detention by Russian troops

The

Nord-Ost

siege. Anna and others take water and juice to the hostages, Moscow, 25 October 2002

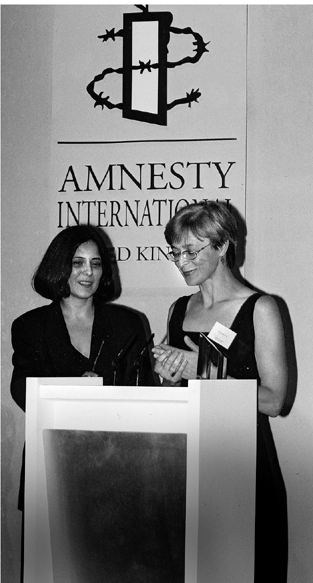

Presentation of the Global Award for Human Rights Journalism by Amnesty International, London, July 2001

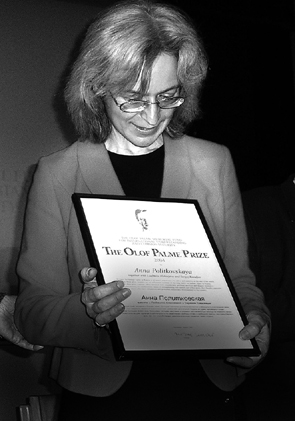

Olof Palme Prize ‘For Courage and Composure While Working in Difficult and Dangerous Conditions’, Stockholm, January 2005

The last image of Anna Politkovskaya, captured by a supermarket CCTV camera, 7 October 2006

March 2002

5. Beslan

One of the most appalling atrocities in the course of the Second Chechen War was the taking hostage in Beslan, North Ossetia, on September 1, 2004 of up to 1,200 people, including 770 children, on the first day of the school year. Russian government troops stormed the school on September 3: 331 hostages died, including 186 children. Here too it seemed that the regime’s primary concern was to manipulate the situation for its own political advantage

. A Russian Diary

contains more of Anna Politkovskaya’s writing on this tragedy

.

WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO POLITKOVSKAYA?

September 6, 2004

By Dmitriy Muratov and Sergey Sokolov (

Novaya gazeta

’s special correspondents in Rostov-on-Don and Moscow)

As the Beslan tragedy has unfolded, hundreds of our journalist colleagues, state officials and readers have been asking what has happened to

Novaya gazeta

’s columnist, Anna Politkovskaya. They believe that her presence in Beslan might have been of value, but Politkovskaya never reached Beslan.

On the evening of September 1, Politkovskaya was sent in

Novaya gazeta

’s car to Vnukovo Airport. Before that she had contacted a number of Russian politicians and Maskhadov’s representative in London, Akhmed Zakayev. The basis of her proposals was that everybody who could get in touch with the terrorists should do so promptly, without considering the consequences, in order to save the children. “Let Maskhadov go and reach agreement with them,” she urged. Zakayev reported that Maskhadov was prepared to do that without conditions or guarantees.

At Vnukovo, flights to Vladikavkaz had been cancelled. Those to nearby towns had also been cancelled. Three times Politkovskaya checked in and three times she was unable to fly. The newspaper ordered her to go to Rostov, and from there to travel onwards by car. The Karat airline allowed her to board.

Politkovskaya had had no time to eat all day. In the plane – and she is an experienced person – she refused food, having taken an oat biscuit with her. She felt fine and asked only for tea from the stewardess. Ten minutes after drinking it, she lost consciousness, having just had time to summon the stewardess back.

Thereafter she remembers only fragments. Valiant efforts were made by the doctors at the Rostov Airport Medical Center to get her out of a coma. They succeeded. The work of the doctors from the Fifth Infectious Diseases Department of Rostov City Hospital No. 1 was irreproachable. In underfunded conditions they revived her by all the means at their disposal, even surrounding her with plastic bottles full of hot water, administering a drip feed, giving injections. By morning she had recovered consciousness.

Grigoriy Yavlinsky, our colleagues from

Izvestiya

, and friends in the Army made every effort to help the medics in what, in the doctors’ opinion, was an almost hopeless task. Many thanks to them.

On the evening of September 3, with the assistance of other friends (thank you, bankers!), Anna was transferred by private plane to one of the Moscow clinics. The Rostov laboratory analysis has not yet been completed. For some incomprehensible reason the first analyses, taken at the airport, were destroyed. The Moscow doctors said openly that they could not yet identify the toxin, but that a poison had entered her body.

Until these circumstances have been clarified, we do not want to engage in conspiracy theories. However, both the situation with Andrey Babitsky, a journalist with Radio Liberty, removed from a flight to the North Caucasus at Vnukovo Airport on suspicion of having explosives in his baggage (!) – needless to say, they found nothing – and the incident with Politkovskaya oblige us to think that attempts were being made to keep a number of authoritative journalists respected in Chechnya from reporting on the tragedy in Beslan.

Politkovskaya is now at home under medical supervision. Her kidneys, liver and endocrinal system have been seriously affected by an unidentified toxin. It is not known how long she will need to convalesce.

Why on earth don’t those officials so exercised by Politkovskaya’s activity just get on with doing their jobs? Averting terrorist acts, for example.

THE HUTS NEED PEACE, THE PALACES NEED WAR

September 13, 2004

The first three days of September 2004 have demonstrated once again that the moral and intellectual level of the Kremlin’s current occupants gives no grounds to hope there will never be another Beslan. The days since the tragedy have demonstrated, moreover, that they have no intention of learning any lessons from the school massacre. They persist with their lies and evasions, and insist that black is white. This leaves our children and grandchildren in danger.

Our state authorities operate out of sight and, during times of national tragedy, they hide. We need people who at the very least will not hide themselves away. The crucial question in the light of recent events is, how have the state authorities responded to the Beslan tragedy? What have they done to improve their citizens’ security?

There has been only one visible response: an administrative “anti-terrorist” reorganization in the South of Russia. In each region a senior “anti-terrorist” officer has been appointed from the ranks of the Interior Ministry’s troops. They rank as second in command to those with overall responsibility for the region. In the current bureaucratic structure, which existed before Beslan, each region has an Anti-Terrorist Commission headed by Presidents Zyazikov, Alkhanov, Dzasokhov, Kokoyev, et al., and they bear full responsibility for terrorist acts on their territories. In addition, the new senior anti-terrorist officers will each command a further 70 special operations troops. The post-Beslan reinforcement of security in the South Russian regions,

accordingly, amounts to 71 extra anti-terrorist agents apiece. Is that it? Yes. It is a typical bureaucratic manoeuvre to avert bad publicity.

What do we actually know about the heads of the Anti-Terrorist Commissions in the South of Russia? Let us cast an eye over the files of some of these gentlemen whose duty was to prevent Beslan from happening and who, after it erupted, were personally responsible for conducting the operation to free the hostages.

Every age has its own characteristics. The Brezhnev era was typified by cynical dementia. Under Yeltsin it was think big, take big. Under Putin, we live in an era of cowardice. Take a look at those who surround him.