Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (38 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

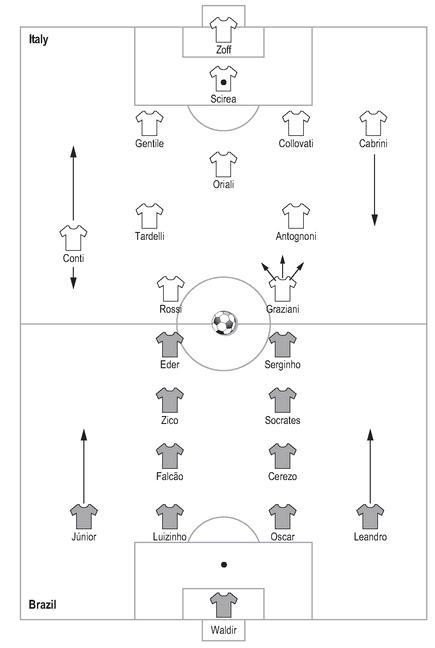

Italy 3 Brazil 2, World Cup second group phase, Sarrià, Barcelona, 5 July 1982

The irony is that ‘

il gioco all’ Italiana

’ was itself dying. ‘It was effective for a while,’ Ludovico Maradei explained, ‘and, by the late 1970s and early 1980s everybody in Italy was playing it. But that became its undoing. Everybody had the same system and it was rigidly reflected in the numbers players wore. The No. 9 was the centre-forward, 11 was the second striker who always attacked from the left, 7 the

tornante

on the right, 4 the deep-lying central midfielder, 10 the more attacking central midfielder and 8 the link-man, usually on the centre left, leaving space for 3, the left-back, to push on. Everyone marked man to man so it was all very predictable: 2 on 11, 3 on 7, 4 on 10, 5 on 9, 6 was the sweeper, 7 on 3, 8 on 8, 10 on 4, 9 on 5 and 11 on 2.’

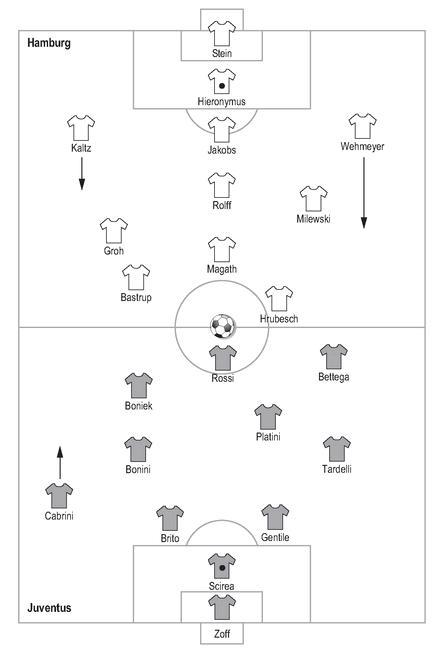

The match in which the shortcomings of

il gioco all’ Italiana

were exposed came less than a year after it had beaten the Brazilian game, as Juventus lost the 1983 European Cup final to SV Hamburg. Three of Juventus’s back-four had played for Italy in Barcelona, with Claudio Gentile and Cabrini as the full-backs and Scirea as the sweeper, the only difference being the presence of Sergio Brio as the stopper central defender. Hamburg played with two forwards: a figurehead in Horst Hrubesch, with the Dane Lars Bastrup usually playing off him to the left. That suited Juventus, because it meant he could be marked by Gentile, while Cabrini would be left free from defensive concerns to attack down the left.

Realising that, the Hamburg coach Ernst Happel switched Bastrup to the right, putting him up against Cabrini. That was something almost unheard of in Italian football. Their asymmetric system worked because everybody was equally asymmetric: the marking roles were just as specific as they had been in the W-M. Giovanni Trapattoni decided to stick with the man-to-man system, and moved Gentile across to the left to mark Bastrup. That, of course, left a hole on the right, which Marco Tardelli was supposed to drop back and fill. In practice, though, Tardelli was both neutered as an attacking force and failed adequately to cover the gap, through which Felix Magath ran to score the only goal of the game.

Hamburg 1 Juventus 0, European Cup final, Olympiako, Athens, 25 May, 1983

How then, were playmakers to be fitted into a system? France, under Michel Hidalgo, and blessed with a side almost as talented as Brazil’s, shifted shape according to the opposition, with Michel Platini playing sometimes as a centre-forward, sometimes in the hole and sometimes more as a

regista

. He was an exceptional player and Hidalgo’s use of him was probably unique, but what is significant is that he asked the playmaker to adjust to the demands of the system, rather than building the side around him. In that it should be said, he was helped by the quality of the players around him: Alain Giresse and Jean Tigana were world-class playmakers in their own right and Hidalgo’s task was simply to find the right balance between creativity and structure; he could reasonably expect chances to arrive.

With Argentina in 1986, Carlos Bilardo had no such luxuries and, hardly surprisingly given he had grown up under Osvaldo Zubeldía, he adopted a more pragmatic approach. In any team, he said, seven outfield players were needed to defend, three to attack. It helps, of course, when one of those three is Diego Maradona. Presenting one of the most system-driven managers of all time with arguably the greatest individual player of all time could have been one of football’s great jokes; as it turned out, it simply inspired Bilardo to the last great formational change, although he claims to have experimented with it for the first time at Estudiantes in 1982.

The trend through history had been to add defenders, from the two of the pyramid to the three of the W-M to the four of pretty much everything post-1958. Bilardo took one away. Or at least, he claims he did. If there were no wingers any more, he reasoned, why bother with full-backs? Since Nílton Santos, full-backs had been becoming more attacking, so why not re-designate them as midfielders and play them higher up the pitch? And so was born the 3-5-2. Played with midfielders in the wide positions, that was what it was; played with attacking full-backs - as for instance West Germany did in 1990 with Stefan Reuter and Andreas Brehme or Croatia in 1998 with Mario Stanić and Robert Jarni - it was a little more defensive; played with orthodox full-backs, it was, although managers habitually denied it, a 5-3-2. The pyramid had been inverted.

Bilardo retired from playing in 1970, and succeeded Zubeldía as manager of Estudiantes the following year. While coaching, he also helped run his father’s furniture business and practised as a gynaecologist, only retiring from medicine in 1976, when he moved to Deportivo Cali in Columbia. He then had spells with San Lorenzo, the Colombia national team and Estudiantes, before being appointed to replace César Luis Menotti after the 1982 World Cup. At that stage, although the two clearly represented fundamentally opposed philosophies of the game, their relationship was relatively cordial.

At least initially, Bilardo spoke glowingly of Argentina’s performance in winning the World Cup in 1978. After he had succeeded Menotti, they met in the Arena Hotel in Seville in March 1983. Menotti told him there that Estudiantes had set back the development of Argentinian football by ten years, but they parted on good terms. Bilardo, though, then ignored his predecessor’s advice and omitted Alberto Tarantini and Hugo Gatti from his squad for his first game, a friendly against Chile, to which Menotti reacted by writing a highly critical piece in

Clarín

. The détente over, they became implacable enemies.

While Menotti spun his visions of

la nuestra

revisited, Bilardo simply got on with the business of winning. ‘I like being first,’ he said. ‘You have to think about being first. Because second is no good, being second is a failure… For me it’s good that if you lose you should feel bad; if you want you can express it crying, shutting yourself away, feeling bad … because you can’t let people down, the fans, everyone, the person who signed you. I’d feel very bad if we lost a match and that night I’m seen out eating calmly in some place. I can’t allow it. Football is played to win… Shows are for the cinema, for the theatre… Football is something else. Some people are very confused.’

In the early part of his reign, Bilardo himself was widely perceived as being confused. His start was disastrous, as Argentina won just three of his first fifteen games, a run that included a humbling exit from the Copa América and a defeat to China in a mini-tournament in India. By the time Argentina embarked on a tour of Europe in September 1984, Bilardo’s position was under severe threat. ‘We were at the airport about to leave, when José María Muñoz, the commentator for Radio Rivadia, came up to me,’ Bilardo remembers. ‘“Don’t worry,” he said. “If we win these three games, everything will be calm again.”’

That, though, seemed far from likely, and when Bilardo read out his team to face Switzerland in the first game of the tour, his reputation had sunk so low that it was widely assumed he had made a mistake. ‘They told me I was wrong, that I’d named three central defenders,’ he said. ‘But I told them I was not confused, that they should not panic, that everything was well. We were going to use three defenders, five midfielders and two forwards. We had practised it for two years, and now I was going to put it into practice in tough games.’

Switzerland were beaten 2-0, as were Belgium, and then West Germany were beaten 3-1. ‘The system worked out, and afterwards we used it in the 1986 World Cup, where the entire world saw it,’ said Bilardo. ‘When we went out to play like that, it took the world by surprise because they didn’t know the details of the system.’

Perhaps, like Alf Ramsey in 1966, Bilardo deliberately decided to shield his new formation from spying eyes; perhaps the truth is that his achievement was rooted less in any grand plan than in strategic tinkering as and when necessary (as, to an extent, was Ramsey’s). Either way, Argentina did not go to Mexico on any great cloud of optimism. They won their last warm-up game 7-2 against Israel, but that was their first victory in seven games. As Maradona put it in his autobiography, fans watched their opening game against South Korea ‘with their eyes half-closed’, fearing the sort of humiliation that was eventually inflicted upon them by Cameroon four years later. ‘They didn’t even know who was playing,’ he went on. ‘[Daniel] Passarella had left; [Jorge Luis] Brown, [José Luis] Cuciuffo and [Héctor] Enrique had come into the squad. We trusted, we trusted, but we had not yet a single positive result to build on… All Bilardo’s meticulous plans, all his tactics, his obsession with positions, suddenly it all fell into place.’

Cuciuffo and Enrique, though, did not play in that opening game. Rather Argentina began with a 4-4-2, with Brown playing as a

libero

behind Néstor Clausen, Oscar Ruggeri and Oscar Garré, and Pedro Pasculli alongside Jorge Valdano up front. Argentina won that comfortably enough, but against Italy, Bilardo decided Cuciuffo would be better equipped to deal with the darting Italy forward Giuseppe Galderisi. Ruggeri took care of Alessandro Altobelli and so, as in

il gioco all’ Italiana

, the left-back, Garré, was left free to push on and join the midfield. The same system was retained for the third group game against Bulgaria and the second-round victory over Uruguay.

It was only against England in the quarter-final that Bilardo settled upon the eleven that would go on to beat Belgium in the semi-final and West Germany in the final (Ramsey, of course, had only settled on his final eleven in a quarter-final against Argentina). In Brown he had a

libero

who seemed a throwback to the days of uncomplicated sweepers like Picchi. In front of him were the two markers, Ruggeri and Cuciuffo, who picked up the opposing centre-forwards. Sergio Batista operated in front of them as a ball-playing ball-winner, with Julio Olarticoechea - preferred to the more defensively minded Garré - and Ricardo Giusti wide. Jorge Burrachaga, as a link between midfield and attack, was a certainty, as, obviously, were Valdano and Maradona, which left just one position left to fill. Pasculli had scored the winner against Uruguay in the previous round, but Bilardo decided to drop him, deciding instead to pick Enrique ‘You can’t play against the English with a pure centre-forward,’ he explained. ‘They’d devour him, and the extra man in midfield will give Maradona more room.’

So Maradona played as a nominal second striker, but given the freedom to roam wherever he saw fit by the defensive platform behind him. His first goal, after fifty-one minutes, was an example of

viveza

at its worst; his second, four minutes later, quite breath-taking. Called upon to attack by the two-goal deficit, the England manager Bobby Robson threw on two wingers in John Barnes and Chris Waddle, and the defensive weaknesses of Bilardo’s system were immediately exposed. Gary Lineker converted a Barnes cross to pull one back, and was a hair’s breadth away from a repeat in the final seconds.

Would a side with wingers have overrun Argentina? Possibly. It could be argued that their central midfield three of Batista, Enrique and Burruchaga would have dominated possession, but they failed to cut out the supply to Barnes and Waddle even against a central midfield duo as lacking in ferocity as Glenn Hoddle and Steve Hodge. Carlos Tápia replaced the more attacking Burruchaga with fifteen minutes to go, but Barnes still ran riot.

Still, it hardly mattered. Belgium had no wide players of any note - who is to say they would have had the courage to play them even if they had? - and restricted their semi-final to a midfield battle, only to be beaten by more Maradona brilliance. In the final, Argentina met a West Germany side going through their own uneasy transition to a wing-back system. The acknowledgement of the possibilities of 3-5-2 seems to have happened all but simultaneously in Europe and South America, and although the outcome was similar, as with the move to 4-2-4, the processes of evolution were different.

After defeat in the 1966 World Cup final West German football had moved slowly towards the

libero

as practised by the Dutch, with Franz Beckenbauer, by 1974, established as an attacking sweeper in a 1-3-3-3. He had played in the role for Bayern Munich from the late sixties, encouraged by Zlatko Cajkovski, their Yugoslav coach, who had grown up in an environment that saw the value in having ball-playing central defenders. It is no coincidence that the first great Ajax

libero

, Velibor Vasović was produced by the same culture. Beckenbauer himself always insisted his attacking style resulted from him playing in midfield for West Germany, where Willi Schulz remained the

libero

, which meant he was less prone to the discomfort defenders commonly felt when advancing with the ball.