Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (13 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

It is important here to clarify exactly what Arkadiev meant by a ‘zonal game’. What he did not mean was the integrated system of ‘zonal marking’ that Zezé Moreira introduced in Brazil in the early fifties and that Viktor Maslov would later apply with such success at Dynamo Kyiv. He was speaking rather of the transition from the simple zonal game of the 2-3-5, in which one full-back would take the left-side and one the right, to the strict system of the W-M, in which each player knew clearly which player he was supposed to be marking (the right-back on the left-wing, the left-half on the inside-right, centre-back on centre-forward etc). In England this had happened almost organically as the W-M developed; with the W-M arriving fully formed in the USSR, there was, inevitably, a period of confusion as the defensive ramifications were taken on board.

Very gradually, one of the halves took on a more defensive role, providing extra cover in front of the back three, which in turn meant an inside-forward dropping to cover him. It was a slow process, and it would be taken further more quickly on the other side of the globe, but 3-2-2-3 was on the way to becoming 4-2-4. Axel Vartanyan, the esteemed historian of Soviet football, even believes it probable that Arkadiev was the first man to deploy a flat back four.

As war caused the dissolution of the league, Arkadiev left Dinamo for CDKA (the forerunner of CSKA) in 1943, and went on to win the championship five times before the club was disbanded as Stalin held them responsible for the USSR’s defeat to Yugoslavia at the 1952 Olympics. Dinamo, meanwhile, continuing to apply Arkadiev’s principles, beguiled Britain with their short-passing style -

passovotchka

, as it became known - as they came on a goodwill tour following the end of hostilities in 1945.

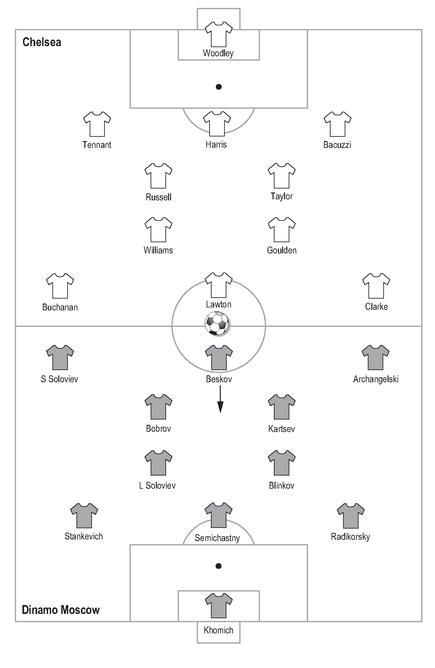

The build-up to their first game, against Chelsea at Stamford Bridge, was marked by political concerns and, more practically, fears that ‘charging’ might become as great a source of dispute as it had been for British sides on those early tours of South America. Chelsea were only eleventh in the Southern Division - a full resumption of the league programme still being several months away - and struggled to a fortuitous 3-3 draw, but their comparative lack of sophistication was clear. Just as Sindelar had tormented England by dropping deep, just as Nándor Hidegkuti would, so Konstantin Beskov bewildered Chelsea by refusing to operate in the area usually occupied by a forward.

The most striking aspect of Dinamo’s play, though, was their energy, and the intelligence with which they used it. ‘The Russians were on the move all the time,’ the Chelsea left-back Albert Tennant complained. ‘We could hardly keep up with them.’ Davie Meiklejohn, the former Rangers captain, wrote in the

Daily Record

: ‘They interchanged positions to the extent of the outside-left running over to the right-wing and vice versa. I have never seen football played like it. It was a Chinese puzzle to try to follow the players in their positions as it was given [

sic

] in the programme. They simply wandered here and there at will, but the most remarkable feature of it all, they never got in each other’s way.’

As Dinamo went on to thrash Cardiff 10-1, beat Arsenal 4-3 and draw 2-2 at Rangers, appreciation of their methods became ever more effusive. In the

Daily Mail

, Geoffrey Simpson spoke of them playing ‘a brand of football which, in class, style and effectiveness is way ahead of our own. As for its entertainment value - well, some of those who have been cheering their heads off at our league matches must wonder what they are shouting about.’ The question then was, was their style related to ideology?

There was talk - again - of their football being like chess, and suggestions that much of Dinamo’s football was based around

Chelsea 4 Dinamo Moscow 4, friendly, Stamford Bridge, London, 13 November 1945

pre-planned moves. It may be an easy metaphor to speak of Communist football being built around the team as a unit with the players mere cogs within it, as opposed to the British game that allowed for greater self-expression, but that does not mean there is no truth to it. Alex James, the former Arsenal inside-forward, wrote in the

News of the World

that Dinamo’s success ‘lies in teamwork to which there is a pattern. There is no individualist in their side such as a [Stanley] Matthews or a [Raich] Carter. They play to a plan, repeating it over and over again, and they show little variation. It would be quite easy to find a counter-method to beat them. This lack of an individualist is a great weakness.’ Or maybe their great individuals - and nobody would have denied that the likes of Beskov, Vsevolod Bobrov and Vasili Kartsev were fine, technically gifted players - simply utilised their gifts in a different way.

Mikhail Yakushin, who had replaced Arkadiev as coach of Dinamo, seemed just as keen to peddle the ideological line as the British press. ‘The principle of collective play is the guiding one in Soviet football,’ he said. ‘A player must not only be good in general; he must be good for the particular team.’ What about Matthews? ‘His individual qualities are high, but we put collective football first and individual football second, so we do not favour his style as we think teamwork would suffer,’ Yakushin replied.

In Britain, this was a revolutionary thought, and it raises an intriguing theory. Broadly speaking, although Bob McGory attempted to replicate the

passovotchka

style at Stoke City to little success - perhaps not surprisingly, given the presence of Matthews in his side - the lessons of the Dinamo tour were ignored. Now, given British football had ignored or patronised developments in South America and central Europe, it is unlikely - even in the revolutionary years immediately following the war - it would ever have cast off its conservatism entirely, but it may have been more open to innovation if it hadn’t been blessed at the time with a glut of great wingers. Why change a formation that allowed the likes of Matthews, Tom Finney and Len Shackleton in England, or Willie Waddell, Jimmy Delaney and Gordon Smith in Scotland, to give full rein to their talents?

Matthews’ finest hour, perhaps the high point of English wing-play, came in the 1953 FA Cup final, when his jinks and feints inspired Blackpool to come from 3-1 down to beat Bolton 4-3. Six months later, on the same pitch, Hungary destroyed England 6-3, and the

Daily Mirror

’s headline proclaimed the ‘Twilight of the (Soccer) Gods’. In terms of the reliance on wingers to provide the artistry, it was right.

The irony, of course, is that Herbert Chapman, the progenitor of the W-M, had been deeply suspicious of wing-play. His system, the first significant tactical development in the English game in almost half a century, had initially circumvented wingers, and yet it ended up being set in stone by them: the very aspect with which his innovation had done away returned to preclude further innovation. For managers with such players, sticking with the tried and tested was the logical thing to do. England’s record in the years immediately following the war was good; they went almost two years without defeat from May 1947, a run that included a 10-0 demolition of Portugal in Estoril and a 4-0 victory over Italy, still the world champions, in Turin. Scotland’s form was patchier, but even they could take comfort from six straight victories from October 1948. The problem was that the glister of those wingers ended up blinding Britain to the tactical advances being made elsewhere, and it would be eight years after the Dinamo tour before England’s eyes were - abruptly - opened.

Chapter Six

The Hungarian Connection

∆∇ The experience of the

Wunderteam

and Dinamo Moscow’s

passovotchka

tour had intimated at the future, but it was only in 1953 that England finally accepted the reality that the continental game had reached a level of excellence for which no amount of sweat and graft could compensate.

The visit of the

Aranycsapat

, Hungary’s ‘Golden Squad’, to Wembley on 25 November that year - the Olympic champions, unbeaten in three years, against the mother of football, who still considered herself supreme - was billed as ‘the Match of the Century’. That might have been marketing hyperbole, but no other game has so resonated through the history of English football. England had lost to foreign opposition before - most humiliatingly to the USA in the World Cup three years earlier - but, other than a defeat to the Republic of Ireland at Goodison Park in 1949, never at home, where climate, conditions and refereeing offered no excuse. They had certainly never been so outclassed. Hungary’s 6-3 victory was not the moment at which English decline began, but it was the moment at which it was recognised. Tom Finney, injured and watching from the press-box, was left reaching for the equine metaphor Gabriel Hanot had used thirty years earlier. ‘It was,’ he said, ‘like cart-horses playing race-horses.’

For the first half of the twentieth century, both from a footballing and a political point of view, Hungary had existed in the shadow of Austria. Their thinking had, inevitably, been influenced by Hugo Meisl and the Danubian Whirl, but the crucial point was that it was

thinking

. In Budapest, as in Vienna, football was a matter for intellectual debate. Arthur Rowe, a former Tottenham player who took up a coaching position in Hungary before being forced home by the war, had lectured there on the W-M in 1940, but, given his later commitment to ‘push-and-run’, it is safe to imagine he focused on rather more subtle aspects of the system than simply the stopper centre-half that so dominated the thoughts of English coaches of the time.

Aside from the negativity to which it leant itself, the major effect of the prevailing conception of the W-M was to shape the preferred mode of centre-forward. Managers quickly tired of seeing dribblers and darters physically dominated by the close attentions of stopper centre-halves, and so turned instead to big battering-ram-style centre-forwards of the kind still referred to today in Britain as ‘the classic No. 9’; ‘the brainless bull at the gate’ as Glanville characterised them. If Matthias Sindelar represented the cerebral central European ideal; it was Arsenal’s Ted Drake - strong, powerful, brave and almost entirely unthinking - who typified the English view.

But just as there would have been no place for

Der Papierene

in England in the thirties, so beefy target-men were thin on the ground in 1940s Hungary. That was troublesome, for 2-3-5 had yielded to W-M in the minds of all but a few idealists: there was a need either for Hungary to start developing an English style of centre-forward, or to create a new system that retained the defensive solidity of the W-M without demanding a brawny focal point to the attack.

It was Márton Bukovi, the coach of MTK (or Vörös Lobogó as they became after nationalisation in 1949), who hit upon the solution after his ‘tank’, the Romania-born Norbert Höfling, was sold to Lazio in 1948. If you didn’t have the right style of centre-forward, rather than trying to force unsuitable players into the position, he decided, it was better simply to do away with him altogether. He inverted the W of the W-M, creating what was effectively an M-M. Gradually, as the centre-forward dropped deeper and deeper to become an auxiliary midfielder, the two wingers pushed on, to create a fluid front four. ‘The centre-forward was having increasing difficulties with a marker around his neck,’ explained Nándor Hidegkuti, the man who tormented England from his deep-lying role at Wembley. ‘So the idea emerged to play the No. 9 deeper where there was some space.

‘At wing-half in the MTK side was a fine attacking player with very accurate distribution: Péter Palotás. Péter had never had a hard shot, but he was never expected to score goals, and though he wore the No. 9 shirt, he continued to play his natural game. Positioning himself in midfield, Péter collected passes from his defence, and simply kept his wingers and inside-forwards well supplied with passes… With Palotás withdrawing from centre-forward his play clashed with that of the wing-halves, so inevitably one was withdrawn to play a tight defensive game, while the other linked with Palotás as midfield foragers.’

Hidegkuti played as a winger for MTK so, logically enough, when Gusztáv Sebes decided to employ the system at national level, it was Palotás he picked as his withdrawn striker. He retained him through Hungary’s Olympic triumph of 1952, when Hidegkuti played largely on the right, but that September, Palotás was substituted for Hidegkuti with Hungary 2-0 down in a friendly against Switzerland. Sebes had made the switch before, in friendlies against Italy and Poland, leading the radio commentator György Szepesi to conclude that he was experimenting to see whether Hidegkuti, by then thirty, was fit enough to fulfil the withdrawn role. Hungary came back to win 4-2, and so influential was Hidegkuti that his position became unassailable. ‘He was a great player and a wonderful reader of the game,’ said Ferenc Puskás. ‘He was perfect for the role, sitting at the front of midfield, making telling passes, dragging the opposition defence out of shape and making fantastic runs to score himself.’

Hidegkuti was almost universally referred to as a withdrawn centre-forward, but the term is misleading, derived largely from his shirt number. He was, in modern terminology, simply an attacking midfielder. ‘I usually took up my position around the middle of the field on [József] Zakariás’ side,’ he explained, ‘while [József] Bozsik on the other flank often moved up as far as the opposition’s penalty area, and scored quite a number of goals, too. In the front line the most frequent goalscorers were Puskás and [Sándor] Kocsis, the two inside-forwards, and they positioned themselves closer to the enemy goal than was usual with … the W-M system… After a brief experience with this new framework Gusztav Sebes decided to ask the two wingers to drop back a little towards midfield, to pick up the passes to be had from Bozsik and myself, and this added the final touch to the tactical development.’

It was Hidegkuti, though, who destroyed England. Their players had, after all, grown up in a culture where the number denoted the position. The right-winger, the No. 7, lined up against the left-back, the No. 3; the centre-half, the No. 5, took care of the centre-forward, the No. 9. So fundamental was this that the television commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme felt compelled in the opening minutes of the game to explain the foreign custom to his viewers. ‘You might be mystified by some of the Hungarian numbers,’ he said in a tone of indulgent exasperation. ‘The reason is they number the players rather logically, with the centre-half as 3 and the backs as 2 and 4.’ They numbered them, in other words, as you would read them across the pitch, rather than by archaic custom: how was an Englishman to cope? And, more pertinently, what was a centre-half to do if the centre-forward kept disappearing off towards the halfway line? ‘To me,’ Harry Johnston, England’s centre-half that day, wrote in his autobiography, ‘the tragedy was the utter helplessness … being unable to do anything to alter the grim outlook.’ If he followed him, it left a hole between the two full-backs; if he sat off him, Hidegkuti was able to drift around unchallenged, dictating the play. In the end Johnston was caught between the two stools, and Hidegkuti scored a hat-trick. Syd Owen, Johnston’s replacement for the rematch in Budapest six months later, fared no better, and England were beaten 7-1.

It wasn’t just Hidegkuti who flummoxed England, though. Their whole system and style of play was alien. It was, Owen said, ‘like playing people from outer space’. Billy Wright, England’s captain, admitted, ‘We completely underestimated the advances that the Hungarians had made.’ It says much about the general technical standard of English football at the time that Wolstenholme was enraptured by Puskás nonchalantly performing half-a-dozen keepie-ups while he waited to kick off. If that sends a shudder of embarrassment down the modern English spine, it is nothing to what Frank Coles wrote in the

Daily Telegraph

on the morning of the game. ‘Hungary’s superb ball-jugglers,’ he asserted with a touching faith in the enduring powers of English pluck, ‘can be checked by firm tackling.’ Little wonder Glanville spoke of it as a defeat that ‘gave eyes to the blind’.

And yet it wasn’t just about technique, perhaps it wasn’t even primarily about technique. Yes, Hungary had, in Puskás, Hidegkuti, Kocsis, Bozsik and Zoltán Czibor, five of the greatest players of the age and, in Sebes, an inspirational and meticulous coach but, as Hungary’s right-back Jenő Buzánszky acknowledged, ‘It was because of tactics that Hungary won. The match showed the clash of two formations and, as often happens, the newer, more developed formation prevailed.’ Perhaps it is wrong to divide the two, for while the tactics permitted the technique to flourish, without the technique the tactics would have been redundant. England were slow to react to the problems (and certainly negligent in failing to address them ahead of the rematch in Budapest six months later), but it is hard to ar˝e that their manager Walter Winterbottom picked the wrong tactics on the day. The problem, rather, was endemic.

England, Geoffrey Green wrote in

The Times

the following morning, ‘found themselves strangers in a strange world, a world of flitting red spirits, for such did the Hungarians seem as they moved at devastating pace with superb skill and powerful finish in their cherry bright shirts. One has talked about the new conception of football as developed by the continentals and South Americans. Always the main criticism against the style has been its lack of a final punch near goal. One has thought at times, too, that perhaps the perfection of football was to be found somewhere between the hard-hitting, open British method and this other more probing infiltration. Yesterday, the Hungarians, with perfect teamwork, demonstrated this mid-point to perfection.’

Not that Sebes saw his Hungary as the mid-point of anything. Having organised a labour dispute at the Renault factory in Paris before the war, his Communist credentials were impeccable and, while he was assuredly saying what his government wanted to hear, there is no reason to believe he was not also voicing his own opinion as he insisted Hungary’s success, so obviously rooted in the interplay of the team as opposed to the dissociated individuality of England, was a victory for socialism. Certainly that November evening, as the flags hung limp in the fog above the Twin Towers, themselves designed to reflect the work of Lutyens in New Delhi, it didn’t take a huge leap of the imagination to recognise Empire’s symbolic defeat.

Football, of course, is not played on the blackboard. However sound the system, success on the pitch requires compromise between - in the best case, stems from a symbiosis of - the theory and the players available. Bukovi’s idea was perfect for Hungary, because four front men and a withdrawn centre-forward permitted a fluidity of attack that suited the mindset of their forwards. It is revealing watching a video of the game today that, midway through the first half, Wolstenholme observes, in a tone midway between amusement and amazement, that ‘the outside-

left

Czibor came across to pick up the ball in the outside-right position’.

Fluidity is all very well, but, of course, the more fluid a team is, the harder it is to retain the structures necessary to defend. That is where Sebes excelled. He was so concerned with detail that he had his side practise with the heavier English balls and on a training pitch with the same dimensions as Wembley, and his notebook shows a similar care for the tactical side of the game. He encouraged the two full-backs, Buzánszky and Mihály Lantos, to advance, but that meant the centre-half, Gyula Lóránt, dropping even deeper, into a position not dissimilar to the sweeper in Karl Rappan’s

verrou

system. Puskás had licence to roam, while Bozsik, notionally the right-half, was encouraged to push forwards to support Hidegkuti. That required a corresponding defensive presence, which was provided by the left-half, Zakariás, who, in the tactical plan for the game Sebes sketched in his notebook, appears so deep he is almost playing between the two full-backs. Two full-backs, two central defensive presences, two players running the middle and four up front: the Hungarian system was a hair’s-breadth from 4-2-4.