Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (8 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

And that, in a sense, was the problem: it was simply easier to be a good defensive centre-half than a good attacking one. The creative part of Chapman’s equation was even harder to fulfil. Inside-forwards of the ability of Alex James were rare, but phlegmatic Herbie Roberts-style stoppers abounded. ‘Other clubs tried to copy Chapman,’ Jimmy Hogan said, ‘but they had not the men, and the result was, in my opinion, the ruination of British football, with the accent on defence and bringing about the big kicking game which put to an end the playing of constructive football. Through this type of game our players lost the touch and feeling for the ball.’

The seeds of that decline may have pre-dated the change in the offside law, but they were nurtured by Chapman’s response to it. The effect of the third-back game, as Glanville said, was ‘to reinforce and aggravate weakness which already existed’ because it encouraged a mental laziness on the part of coaches and players. It is far less arduous, after all, to lump long balls in the general direction of a forward than to endure the agonies of creation. Chapman, though, remained unapologetic. ‘Our system, which is so often imitated by other clubs, has lately become the object of criticism and discussion…,’ he told Hugo Meisl. ‘There is only one ball in play and only one man at a time can play it, while the other twenty-one become spectators. One is therefore dealing only with the speed, the intuition, the ability and the approach of the player in possession of the ball. For the rest, let people think what they like about our system. It has certainly showed itself to be the one best adapted to our players’ individual qualities, has carried us from one victory to another… Why change a winning system?’

Chapman himself never had to, nor did he have to deal with the transition from one generation of players to the next. On 1 January 1934, he caught a chill during a game at Bury, but decided to go anyway the next day to see Arsenal’s next opponents, Sheffield Wednesday. He went back to London with a high temperature, but ignored the advice of club doctors and went to watch the reserves play at Guildford. He retired to bed on his return, but by then pneumonia had set in, and he died early on 6 January, a fortnight short of his fifty-sixth birthday.

Arsenal went on to win the title, and made it three in a row the following year. A few months after his death, a collection of Chapman’s writings was published. In it, intriguingly, he too seemed to express regret for the passing of a less-competitive age. ‘It is no longer necessary for a team to play well,’ he said. ‘They must get goals, no matter how, and the points. The measure of their skill is, in fact, judged by their position in the league table.’

This, now, seems all but axiomatic; it is a measure of how pervasive the amateur inclinations of the game remained that even Chapman seems to have felt it necessary to apologise for winning. ‘Thirty years ago,’ he went on, ‘men went out with the fullest licence to display their arts and crafts. Today they have to make their contribution to a system.’ And so, finally, resolved to winning, football recognised the value of tactics, the need for individuality to be harnessed within the framework of a team.

Chapter Four

How Fascism Destroyed the Coffee House

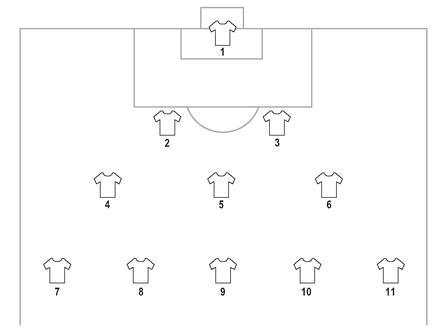

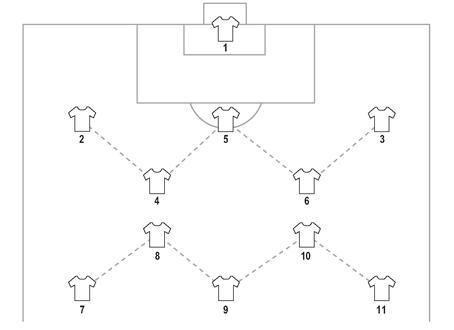

∆∇ Herbert Chapman was one man, making one change to answer a specific problem. English football followed him because it saw his method worked, but the coming of the third-back game did not herald the coming of a generation of English tacticians. ‘Unfortunately,’ as Willy Meisl wrote, ‘the plaster cast remained, no soccer sorcerer or professor was here to smash it to pieces and cast it in another mould.’ If anything, the preference was to try to pretend the tactical change had not happened, that the sacred pyramid remained intact. When the FA made shirt numbering compulsory in 1939, they ignored later developments and stipulated that the right-back must wear 2, the left-back 3, right-half 4, the centre-half 5, the left-half 6, the right-winger 7, the inside-right 8, the centre-forward 9, the inside-left 10 and the left-winger 11, as though the 2-3-5 were still universal, or at least the basis from which all other formations were mere tinkerings. That meant that teams using the W-M lined up, in modern notation, 2, 5, 3; 4, 6; 8, 10; 7, 9, 11, which is why ‘centre-half’ is - confusingly - used as a synonym for ‘centre-back’ in Britain.

Newspapers, similarly, ignored the reality, continuing to print team line-ups as though everybody played a 2-3-5 until the 1960s. Even when Chelsea played the Budapest side Vörös Lobogó in 1954, and - alerted to tactical nuances by the fall-out from England’s 6-3 defeat to Hungary at Wembley a year earlier - made the effort to print the Hungarian formation correctly in the match programme, they persisted with the delusion that their own W-M was actually a 2-3-5. So overwhelmingly conservative was the English outlook that the manager of Doncaster Rovers, Peter Doherty, enjoyed success in the fifties with his ploy of occasionally having his players switch shirts, bewildering opponents who were used to recognising their direct adversary by the number on their back.

Numbering in a 2-3-5

Numbering in a W-M (England)

For the importance of tactics fully to be realised, the game had to be taken up by a social class that instinctively theorised and deconstructed, that was as comfortable with planning in the abstract as it was with reacting on the field and, crucially, that suffered none of the distrust of intellectualism that was to be found in Britain. That happened in central Europe between the wars. What was demonstrated by the Uruguayans and Argentinians was explained by a - largely Jewish - section of the Austrian and Hungarian bourgeoisie. The modern way of understanding and discussing the game was invented in the coffee houses of Vienna.

Football boomed in Austria in the twenties, with the establishment of a two-tier professional league in 1924. That November the

Neues Wiener Journal

asked, ‘Where else can you see at least 40-50,000 spectators gathering Sunday after Sunday at all the sports stadiums, rain or shine? Where else is a majority of the population so interested in the results of games that in the evening you can hear almost every other person talking about the results of the league matches and the club’s prospects for the coming games?’ The answer was easy: Britain aside, nowhere else in Europe.

But where in Britain the discussion of games took place in the pub, in Austria it took place in the coffee house. In Britain football had begun as a pastime of the public schools, but by the 1930s it had become a resolutely working-class sport; in central Europe, it had followed a more complex arc, introduced by the Anglophile upper middle classes, rapidly adopted by the working classes, and then, although the majority of the players remained working class, seized upon by intellectuals.

Football in central Europe was an almost entirely urban phenomenon, centred around Vienna, Budapest and Prague, and it was in those cities that coffee-house culture was at its strongest. The coffee house flourished towards the end of the Habsburg Empire, becoming a public salon, a place where men and women of all classes mingled, but which became particularly noted for its artistic, bohemian aspect. People would read the newspapers there; pick up mail and laundry; play cards and chess. Political candidates used them as venues for meetings and debates, while intellectuals and their acolytes would discuss the great affairs of the day: art, literature, drama and, increasingly in the twenties, football.

Each club had its own café, where players, supporters, directors and writers would mix. Fans of Austria Vienna, for instance, met in the Café Parsifal; Rapid fans in the Café Holub. The hub of the football scene in the inter-war years, though, was the Ring Café. It had been the hang-out of the anglophile cricket community, but by 1930 it was the centre of the broader football community. It was, according to a piece written in

Welt am Montag

after the war, ‘a kind of revolutionary parliament of the friends and fanatics of football; one-sided club interest could not prevail because just about every Viennese club was present.’

The impact of football on the wider culture is made clear by the career of the Rapid centre-forward Josef Uridil. He came from the suburbs - in the Vienna of the time edgy, working-class districts - and his robust style of play was celebrated as exemplifying the proletarian roots of the club. He was the first football hero of the coffee house, and, in 1922, became the subject of a song by the noted cabaret artist Hermann Leopoldi, ‘

Heute spielt der Uridil

’, which was so successful that it spread his fame even to those with no interest in football. He began advertising a range of products from soap to fruit juice and, by February 1924, he was appearing as a compère at a music hall while at the same time

Pflicht und Ehre

, a film in which he appeared as himself, was showing in cinemas.

It was into that environment that Hugo Meisl’s

Wunderteam

exploded. The trend through the late twenties was upward and, despite a poor start, Austria narrowly missed out on the inaugural Dr Gerö Cup, a thirty-month league tournament also featuring Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Italy and Switzerland. After losing three of their opening four games, they hammered Hungary 5-1 and the eventual winners Italy 3-0, finishing runners-up by a point. In the Ring, they weren’t satisfied, and agitated for the selection of Matthias Sindelar, a gifted, almost cerebral, forward from Austria Vienna, a club strongly associated with the Jewish bourgeoisie.

He was a new style of centre-forward, a player of such slight stature that he was nicknamed ‘

Der Papierene

’ - ‘the Paper-man’. There was an air of flimsy genius about him that led writers to compare his creativity to theirs: a fine sense of timing and of drama, a flair for both the spontaneous and the well-crafted. In his 1978 collection

Die Erben der Tante Jolesch

, Friedrich Torberg, one of the foremost of the coffee-house writers, wrote that: ‘He was endowed with such an unbelievable wealth of variations and ideas that one could never really be sure which manner of play was to be expected. He had no system, to say nothing of a set pattern. He just had … genius.’

Hugo Meisl, though, was doubtful. He had given Sindelar his international debut as a twenty-three year old in 1926 but, for all that he stood in the vanguard of the new conception of football, Meisl was, at heart, a conservative. Everything he did tactically could be traced back to a nostalgic attempt to recreate the style of the Rangers tourists of 1905: he insisted on the pattern-weaving mode of passing, ignored the coming of the third back, and retained a sense that a centre-forward should be a physical totem, somebody, in fact, like Uridil.

Uridil and Sindelar were both from Moravian immigrant families, both grew up in the suburbs and both became celebrities (Sindelar too played himself in a film and supplemented his footballer’s income by advertising wrist-watches and dairy products), but they had little else in common. As Torberg put it, ‘They can only be compared as regards popularity; in terms of technique, invention, skill, in short, in terms of culture, they were as different from each other as a tank from a wafer.’

Finally, in 1931, Meisl succumbed to the pressure and turned to Sindelar, installing him as a fixture in the team. The effects were extraordinary, and on 16 May 1931, Austria thrashed Scotland 5-0. Two-and-a-half years on from the Wembley Wizards’ 5-1 demolition of England, Scotland found themselves just as outmanoeuvred by the same game, taken to yet greater heights. They were, admittedly, without any Rangers or Celtic players, fielded seven debutants and lost Daniel Liddle to an early injury, while Colin McNab played on as a virtual passenger after suffering a blow to the head towards the end of the first half, but the

Daily Record

was in no doubt what it had witnessed: ‘Outclassed!’ it roared. ‘There can be no excuses’. Only the heroics of John Jackson, the goalkeeper, prevented an even greater humiliation.

Given England had been beaten 5-2 by France in Paris two days earlier, that week now seems to stand as a threshold, as the moment at which it became impossible to deny the rest of the world had caught up with Britain (not that that stopped the British newspapers and football authorities trying). The

Arbeiter-Zeitung

caught the mood perfectly. ‘If there was an elegiac note in watching the decline of the ideal the Scots represented for us, even yesterday, it was all the more refreshing to witness a triumph that sprang from true artistry,’ it wrote. ‘Eleven footballers, eleven professionals - certainly, there are more important sides to life, yet this was ultimately a tribute to Viennese aesthetic sense, imagination and passion.’

For the

Wunderteam

, that was just the beginning. Playing a traditional 2-3-5 with an elegant attacking centre-half in Josef Smistik - but with an unorthodox centre-forward who encouraged such fluidity that their system became known as ‘the Danubian Whirl’ - Austria won nine and drew two of their next eleven games, scoring forty-four goals and winning the second edition of the Dr Gerö Cup in the process. The coffee houses were jubilant: their way of doing things had prevailed, largely because of Sindelar, a player who was, to their self-romanticising eye, the coffee house made flesh. ‘He would play football as a grandmaster plays chess: with a broad mental conception, calculating moves and countermoves in advance, always choosing the most promising of all possibilities,’ the theatre critic Alfred Polgar wrote in his obituary in the

Pariser Tageszeitung

, an article remarkable for how many fundamental themes it drew together.