Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes (9 page)

Read Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes Online

Authors: Kamal Al-Solaylee

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Middle East, #General

By 1976, my oldest brother, Helmi, was the first to bring some of these hardened attitudes inside the family home. A handsome, secular law student at Cairo University, Helmi fell under the spell of rebellious Egyptian middle-class men his age who discovered that neither socialism nor Sadat’s new free-trade philosophy and nascent pro-capitalism would improve lives. Islam, until then relegated to the sides of the political landscape, emerged as an alternative. For many years Sadat’s mantra went something like this: No politics in religion and no religion in politics. It outraged young Egyptians and the Muslim groups, which until then had been relatively quiet. I wish I could say the ideological shift in Helmi was gradual, or that our parents had time to wean him off it. The truth is that one summer day in 1976, he woke up to tear down the posters of movie stars in his room (including a gorgeous one of Clint Eastwood circa 1973 that I secretly adored), rearranged his bedroom to make space for a prayer mat that faced Mecca, and just like that found Islam.

Even though Helmi’s notion of a return to Islam would be called moderate by today’s standards of militarized hard-liners, my father—ever the secularist—became deeply concerned about this conversion. For one thing, it meant that Helmi was mixing with young men beneath his social status, and for another, it became a case of a son trying to control family destiny while the father was still alive and well. Islam undercut Mohamed’s authority as a patriarch. He did try to change Helmi’s new direction. He’d often challenge him on his notion of Allah as a furious, punitive force. To my father, Islam was more about ethics, compassion and charity. It had nothing to do with banning belly dancers or censorship of art and culture. And it certainly should not interfere with how money was made or interest rates were determined. “Why would God throw me in hell,” he argued with Helmi, who would reply, “Because you don’t pray five times a day or fast at Ramadan.” Mohamed would counter by saying that he went about his business and raised eleven children, and raised them well. That to him was more important than praying or fasting.

But if Helmi’s change of direction was fought on a symbolic and ideological level with his father, it was the beginning of an oppressive time for my sisters from which they have not yet recovered—and which long ago eroded their will to resist.

MY FIVE REMAINING SISTERS

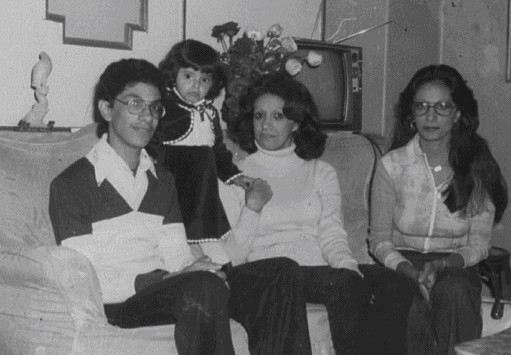

in Cairo—Farida, Ferial, Hoda, Hanna, Raja’a—were very much integrated into Egyptian society. That meant coming and going as they pleased, wearing whatever they thought was fashionable and appropriate, including miniskirts, and applying as much or as little makeup as the occasion demanded. I loved that about my sisters and my parents back then. The family pictures of the time stand as testaments to the last great wave of Arab social liberalism and secularism.

For young women like my sisters in the Cairo of the early 1970s, the idea of wearing a hijab was unthinkable. To young Egyptians, it symbolized poor and uncultured country folks—the kind who were to serve as maids and not as fashion models. (The hijab’s association with oppression of women is a newer, Western phenomenon.) Egypt’s large cities—Cairo and Alexandria—had gone through a great period of modernization starting in the 1920s, during which women adopted Western dress and abandoned traditional garb. That came to an end in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s.

Nothing symbolized the freedom we had as a family as much as our annual summer vacations in Alexandria and the bikini-shopping ritual beforehand in downtown Cairo, which brought out the fashionista in me, even at the tender age of ten or eleven. I looked forward to it every summer and spent the weeks before going through women’s magazines and cutting out my favourite designs. I have absolutely no recollection of the men in the family raising any objections, although I suspect that my parents were secretly concerned about indulging this feminine side. Egyptian cinema featured several distressing stereotypes of the effete (never explicitly described as gay) fashion designer, florist or dance instructor. By the end of the movie these figures often got humiliated by the macho leading man. I wonder if my mother thought I was headed in that direction—which I certainly was.

My father dressed in a suit even for a day at the beach with his children. This photo shows our last family trip to Alexandria, Egypt, in 1976. A mere year or two later, the thought of my sisters wearing bikinis was unacceptable.

“The colour of this brown two-piece makes you look darker,” I’d tell my sister Raja’a as she went through the swimwear selection in a crowded shop near Talat Harb Street in downtown Cairo. She picked a lime-green bikini instead. “I love this one so much I want to wear it myself,” I blurted out to Ferial, clinching her choice of a black-and-white striped swimsuit. When we eventually got to the beach, Mohamed—in his summer suit and tie—and Safia would listen to the radio or talk to other Egyptian families nearby while all the children got into the water. None of us were swimmers as such, but the point was to leave Cairo for two weeks at the hottest time of the year.

I believe that our last trip was in 1976. By the following year, Helmi’s embrace of Islam was getting stricter, and his constant berating of our sisters for their love of “risqué” clothes or excessive makeup was drowning out my father’s constant praise. His daughters were

helween

(beautiful), he’d tell them. When Mohamed was really feeling generous and Safia was within earshot, he’d add, “Just like your mother.” The old flirt may have lost his wealth but not his way with women. His women, at least. It must have been hard on him to realize that all the women he prided himself on catching back in Aden were probably into him for the money. In Cairo, while still comfortable, he was just a middle-aged man with eleven children.

EVEN AS A CHILD

I did not escape Helmi’s transformation. I looked up to him, but he’d ignore me until I joined him in prayer, which even at thirteen or so I didn’t feel like doing. I didn’t understand the point of being religious; I associated it with old people. During the holy month of Ramadan, I’d hear no end of it if I didn’t fast or if I spent the day playing instead of reading the Quran. “Leave him alone—he’s still a baby,” my mother told Helmi repeatedly. “He’s as big as a horse,” Helmi would answer back. I was already nostalgic for the days when we were an all-secular household. My immediately older brother, Khairy, was more amenable to this new form of religious observance, and soon enough he was telling me and my other brother, Wahbi, off for not praying or going to the mosque on Fridays with him and Helmi. Wahbi and I cared more about music and film and were in the habit of sneaking out to movie theatres on Fridays (our day off from school) to watch the latest Arabic or foreign releases. Going to a mosque seemed like a waste of a weekend. Who needed to spend his free day listening to an angry imam and watching scores of men nodding in agreement?

My sisters Raja’a (right) and Ferial and I pose with our first-born niece, Rasha, in 1978. Note my afro—I was also wearing bell-bottomed jeans and high heels. I’d started listening to American disco music by then and liked the fashion that accompanied it.

Similarly, my sisters did their best to ignore Helmi’s criticism (and later Khairy’s) and continue with their regular beauty and fashion routine. But there was only so much you could do before you started self-censoring—self doubting is more like it—and taking safer options. The skirts got longer, the makeup lighter. Dyeing their hair was for special occasions. A new reality set in.

My sister Farida, Child Number Three in the family and the next in line to get married, had a glamorous career and looks to match. Statuesque, even-tempered, with a good secretarial training from the American University in Cairo’s School of Continuing Education, Farida found a job in 1974 as a secretary at the Liberian embassy in Cairo. Her salary of three hundred US dollars a month would have been considered very high in Cairo back in the 1970s, and probably by many Egyptians today. More importantly, the job opened up the world of the international diplomatic community to her, which came with parties, receptions and a string of gentlemen admirers. I’d sit up in the early evenings during the school year and watch her apply her makeup or get dressed in the room she shared with two of my other sisters. It didn’t take me long to insist that she come to school on parent-teacher nights. My mother must have known I was afraid it would be discovered that she was illiterate, and she often came up with an excuse not to go and asked Farida to fill in for her.

There were months when Farida’s take-home pay exceeded what my dad earned from his savings. She was expected to cover household expenses, which made my mother angry. Safia wanted her husband to stop messing about and get some work—not live off his own daughter. My parents started to argue more frequently and passionately about money. We lived in fear of yet another fight. My mother may have been uneducated, but she never backed down from arguing with Mohamed when it came to providing for her children. When my grandparents would visit—especially my father’s parents—they repeatedly asked her not to butt heads with their son, as he was the man of the house. “You should know better,” they told her. When my grandmother was feeling particularly vindictive, she’d remind Safia that Mohamed could have married a more beautiful and lighter-skinned girl. She’d add that it was not too late for him to seek a less nagging wife. My father would have been fifty-two or fifty-three, which I guess was not too old for a second marriage, but the idea of leaving the mother of his children only came up during fights. All this took place in front of us children. It was a lesson not in family relations but in money management. Even before I fully apprehended the meaning of my sexuality, I made up my mind not to have more than one or two children so I could afford to raise them. When I told my brother Wahbi this before we went to the movies, he laughed and told me not to be so melodramatic.

ONCE MOHAMED REALIZED

that our survival depended on the income of one of his daughters, he finally abandoned his pride and in 1978 sought employment in Saudi Arabia. The Gulf countries had a severe labour shortage and recruited heavily from countries with surplus populations like Egypt or Lebanon, where the civil war was into its third year by then. He found a job as an independent contract and business negotiator for a number of well-to-do Saudi families of Yemeni extraction, including the powerful dynasty of bin Laden—a name that was associated with obscene wealth long before it became a symbol of Islamic terrorism. Of course, our connection with the bin Ladens went back to the early decades of the twentieth century, as my mother was born and raised in their native Hadhramaut.

Because of visa regulations, only my father as a businessman could enter and work in Saudi Arabia in the 1970s. That meant leaving his family behind for the first time since the late 1940s, when he sailed from Aden to study in England. Mohamed talked often about the hardship of working in Saudi Arabia—living alone, the egotism and capriciousness of the local businessmen and, particularly for the secular philanderer from Aden, the kind of religious intolerance he observed in the country. He’d often tell us about the “barbaric” custom of the religious observance police, the

mutaween

, who rounded up people during prayer time and herded them into mosques. But a decade of no serious work or income meant having to put his personal beliefs aside and adopt, in appearance at least, a kind of religious piety that would keep his business associates happy.

Back in Cairo, Helmi’s grip on his sisters only strengthened with our father’s frequent absences. Ironically and appropriately enough, Helmi struggled to finish law school at Cairo University even when his supposed new religiosity freed up the time he had spent, say, watching TV or hanging out with his family at the Ahli Club, the sports and social club we were members of in the Gezira part of Cairo. The more courses he failed, the more observant he became. “Maybe he should pick up a textbook instead of the Quran,” my mother would tell her neighbour, the widowed wife an army captain, during one of their regular lunchtime chats.