Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes (5 page)

Read Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes Online

Authors: Kamal Al-Solaylee

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Middle East, #General

The home was easier. After all, a real-estate developer who also happened to know Beirut reasonably well could make his way through the available inventory fast. At the recommendation of a friend, Mohamed and Safia left my sisters Faiza and Farida to look after the children and went to check two interconnected apartments in the then-upscale apartment complex known as the Yacoubian Building. He may have been down and out, but Mohamed would not live below his normal standards. “Too big and expensive,” my mother warned him. “I have money,” he told her, resenting the suggestion that he could no longer afford the finer things in life, which had become second nature to him over the previous twenty-two years. I don’t think he was all that concerned about the cost. To him, this would be a short-term option—the people of Aden wouldn’t tolerate the injustice some idealist socialists had inflicted on him, one of society’s pillars. In a year or so—”I give it to next June,” he wagered optimistically—we’d all be back in Aden. Life would return to normal.

“Sign here,” urged the property manager of the Yacoubian Building as my mother tried in vain to dissuade Mohamed from making such a big financial commitment. Sensing that the deal might fall through, the crafty realtor appealed to my father’s sense of vanity, which he spotted immediately. He mentioned in a tone half-casual, half-deliberate that the famous Lebanese singer Fahd Ballan and his wife, Egyptian screen goddess Mariam Fakhr Al-Din, called this their home. I don’t know if there’s a record for how fast a man has signed a lease, but I’m sure Mohamed holds it. A great building with celebrity residents meant that his place in the world remained unchallenged. Revolutionaries and socialists be damned.

One thing he got right. It was a solid building, the kind he would have introduced to Aden had the socialists not taken it over. Revisiting the complex in 2010, almost forty-three years after we had moved in, I was relieved to see it was still standing. It had survived a fifteen-year civil war that destroyed or badly damaged many of the neighbouring properties. Of course, it was rundown and there was less greenery, as more buildings had sprung up around it in the still-beautiful residential area of Caracas. If any artists lived there, they’d be of the struggling and not the glamorous kind. Surprisingly, the elevator with the blue door that we took up and down to the sixth floor still functioned.

On the balcony of our apartment in the Yacoubian Building in Beirut in 1968, the youngest four children pose for a casual photo. (Left to right: Wahbi, Raja’a, me and Khairy.)

But if finding a home was just a matter of aiming and paying high, choosing schools would be more difficult—even if Mohamed offered to pay full tuition or donate to the school. Knowing how strict school boards tended to be in the central areas of Beirut (imagine a parent calling up Admissions in November to see if they had room for nine children in a day or two), he targeted the suburbs and mountain areas, where the population was less dense and administrators more likely to be charmed by his worldly ways and understanding of local culture. Mohamed loved Lebanese Arabic, which he thought was the classiest version of the language, and loved practising it at home. One school that took students from kindergarten to high school stood out. Literally, as it sat atop the mountainous hamlet of Kafr Shima, about a forty-five-minute drive outside Beirut. Saint Paul’s, a Catholic school, admitted all religious faiths and denominations. Mohamed knew that he had to get his children into this school. Having all of them in one place would make the commute easier and the older siblings could look after the younger ones, eliminating the need for him or my mother to go to school whenever a child got sick or into trouble.

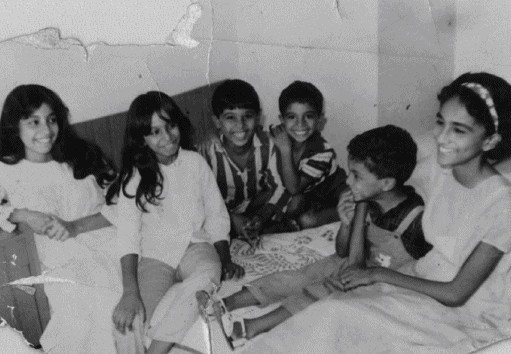

We rarely played with other kids in Beirut. In this photo from 1968, my sister Hoda holds me while Hanna and Raja’a smile affectionately at something I said. Wahbi and Khairy look at the camera with their best and goofiest smiles.

I’m not sure what he did or said, but within a week of arriving with nothing but our luggage, we had a home, a school and a new life in Beirut. I’m too young to remember the early days, but as they did about our time in Aden, my family often reminisced about Beirut. It seemed to have everything for a large family of teens and young children to prosper: great beaches, beautiful neighbourhoods, a lively literary, film and theatre culture, excellent shopping. Back then (and it’s still the case today), Beirut and Cairo were the two cultural centres of the Arab world. Each boasted a prestigious American university and competed for dominance in music and film. Lebanon’s two big divas, Fairouz and Sabah, occupied a special place in the Arab world—the first the height of romanticism and the second of glamour. It was a good time to be a family in Beirut.

My mother didn’t see it that way. The Lebanese loved sprinkling their Arabic with either English or French. Her uncultured Yemeni Arabic made her sound like a hick—even in the company of her own husband, who was comfortable with English and passed for a Lebanese when he wanted to. Safia insisted on taking one of her older daughters with her to the market to do the grocery shopping for the first few months until she felt more comfortable in her new world and had memorized the French or English names that locals used for fruits and vegetables.

Mohamed, on the other hand, had to face the possibility that what might have started as a temporary relocation could turn into a long-term situation. His assets in Aden’s banks were frozen, so for now his only source of income would have to be the funds he’d stashed away in Britain over the years. One thing about these old colonial types: their faith in England may be annoying and retrograde, but it pays off in some ways. The money in Britain was what he called his last safety net, and even in running his worst-case scenario by Safia in Aden, he never thought he’d have to dip into it.

IF MOHAMED FACED

financial ruin, he certainly didn’t let his children know or feel its effects. While the days of extravagance in Aden were behind us, we enjoyed a privileged life compared to that of many Arab families—and even other expatriate Yemeni families. The only sign of retrenching that I can recall was a huge household ledger where my sister Farida was asked to enter every expense that she or my mother incurred. But Mohamed compensated for that with a generous helping of art and entertainment. Lebanese popular culture, like much of the country itself, combined both Western and Arabic influences. As young men and women, my siblings could play a record by Fairouz, to be followed by the latest Beatles single, imported from England. I believe that my family’s cultural awareness was formed in Beirut. It was also a scenic place to live—the sea, the mountains, the Roman and Greek ruins. Mohamed took the youngest six children for weekly outings that consisted of either a movie and dinner or just dinner at one of the outdoor restaurants in the more touristy parts of the Raouché neighbourhood. We’d often pose for a photograph or two. We looked like a typical happy family: mother, father and six children, three boys and three girls. But as I look at these same photographs, I wonder now what Mohamed was thinking and how he planned to raise a family as large as his without any real prospect of work or return of income from his property.

The first few months of idyllic living—for the children at least—might have been a fool’s paradise anyway. Nearly two decades after the establishment of Israel and the displacement of Palestinians, who became the new underclass in Lebanon and Jordan, the sectarian grudges and skirmishes that divided Lebanon along Druze, Shiite and Christian lines were escalating. “

Ya

Allah, ya Allah

,” Mohamed would murmur whenever he saw a news report of an act of violence—a Christian church desecrated or a Muslim business attacked. Our parents advised us children to keep away from Palestinians as troublemakers, to put it mildly. Like many Arabs, they thought nothing of rejecting the Palestinians on a personal basis while recognizing the injustice done to them as a pan-Arab political issue.

Even for a walk downtown and a Sunday matinee, my father dressed in a suit and tie and insisted on a family portrait with his wife and youngest six children.

Still, nothing might come out of the sectarian violence, Mohamed thought, and he continued to insist that our sojourn in Beirut would end soon enough and we’d return to Aden. His favourite phrase when referring to acts of violence in Beirut was the Arabic for “isolated incidents,” an idea he must have been clinging to because to believe otherwise was to accept that he had moved his family to the wrong country. The first anniversary of our expulsion came and went and there was still no sign of a change of heart in Aden. If anything, the socialist regime adopted a harder line, aligning itself closer with the Soviet Union and China and pushing Mohamed’s dreams of reclaiming his property further from reality.

No one in the family knew for sure what he was up to all day. He had rented a little office in downtown Beirut that he dutifully visited on weekdays. With another expatriate dreamer from Aden, he opened up what was euphemistically known as an export/import business. Translation: anything that came their way. I don’t think they made a penny in their first year in business and in all probability lost much of their capital in office rental and, in my father’s case, a taxi to and from work every day. (He never took public transport in the Middle East.) Many of the business suits that he’d wear for almost twenty years in Cairo were bought in Beirut at that time. Suits, ties and cufflinks. He wore them even when he took us to a beach. As he didn’t have the capital to start a real-estate business and was probably too smart to invest in such an illiquid asset ever again, Mohamed knew he’d always be a small fish from here on.

AS I WAS JUST

over three years old when we moved to Beirut, I couldn’t join my siblings at Saint Paul’s School in Kafr Shima. Instead I stayed home, and Faiza, who had already gone to high school in Aden but didn’t wish to go to university, looked after me. My earliest memories of Beirut are of two things that influenced the person I became: music and men. Faiza loved collecting records and would spend all her spare money on Arabic LPs by the likes of Oum Kalthoum, Farid Al-Attrach and Shadia. By the time I was four, I could tell different singers by voice, or at least by the label on the vinyl record. Our daily morning game went something like this: Faiza would play a few seconds from a record and ask me who was singing. When she wanted time for herself, she’d send me back to my mother in the kitchen. “It’s your turn,” she’d say, and I’d sit in my three-wheel bike watching Safia cook lunch for twelve people.

When both were busy, they’d just park me in front of the TV or give me Arabic celebrity magazines and tell me to look at the pictures. I wasn’t five yet when I noticed that I loved looking at a Palmolive ad on TV (and in print) that featured a hairy man, all lathered and grinning because he’d just showered with that brand of soap. Of course I didn’t know what that sensation was, but in retrospect it was my earliest homoerotic experience. I was also strangely drawn to the husband, Darrin, on

Bewitched

, which was shown on primetime Lebanese TV. (I didn’t realize that two actors played the same part until I saw the show on reruns in Canada decades later.) To me, TV was a gateway into a world of pleasures I couldn’t even understand. Whenever I saw Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez on TV, I’d get a strange feeling. He stood out as handsome, romantic and not quite as macho as other actors of his generation.