Insomnia and Anxiety (Series in Anxiety and Related Disorders) (19 page)

Read Insomnia and Anxiety (Series in Anxiety and Related Disorders) Online

Authors: Jack D. Edinger Colleen E. Carney

most of the herbal compounds and supplements mentioned here so their use as

sleep aids cannot be recommended.

Melatonin

Unlike the other compounds mentioned, melatonin is a hormone that is produced

by the pineal gland and, thus, occurs naturally in the human body. Melatonin is

synthesized from serotonin and mostly is secreted at night. Typically, melatonin

concentration levels in the blood begin to rise around dusk, reach a peak during the

middle of the night, and then decrease around dawn. Melatonin seems to have influ-

ences on the endogenous circadian system that regulates the timing of sleep in the

24-h day. For this reason, melatonin has been used to alter the timing of the sleep–

wake schedule under such conditions as jet lag, or to reset the biological clock in

those who have marked endogenous delay in the timing of their sleep onset each

night. In applications to insomnia, some studies have shown that melatonin results in

self-reported improvements in sleep onset latency and general sleep quality, but its

effects on other self-reported sleep measures is more equivocal (Buysse et al., 2005).

In addition, some studies suggest that melatonin administration leads to objective

Over-the-Counter Medications, Herbal Remedies, and Alternative Treatments

69

improvements in sleep latency (Hughes, Sack, & Lewy, 1998; Zhdanova et al.,

2001). However, a recent comprehensive review of the melatonin literature suggested

that the research supporting the use of this agent as an insomnia remedy is of

questionable quality (Buscemi et al., 2004).

Currently, melatonin sold over-the-counter does not have an FDA-approved

indication for insomnia and, therefore, it is not regulated by the FDA. As such,

formulations sold to the general public are not standardized in their compositions.

However, the side effects associated with melatonin use appear to be minimal.

The most common side effect is headache. In rare cases, other side effects includ-

ing disorientation, nausea, seizures, and shortness of breath have been reported

(Buysse et al., 2005). Nonetheless, for most individuals, short-term use to address

insomnia is safe, but little data currently exist concerning its long-term effects.

Alcohol

Alcoholic beverages are widely used as a common home remedy for sleep difficul-

ties. In fact, it is estimated that as many as 30% of all chronic insomnia sufferers

use alcohol as a routine sleep aid (Ancoli-Israel & Roth, 1999). Alcohol is a CNS

depressant and, as such, has a relaxing and sleep-inducing effect, particularly on

anxious individuals. It tends to reduce sleep onset time and increase the amount of

nonrapid eye movement sleep (NREM) while reducing rapid eye movement sleep

(REM) during the initial half of the night (Gillin, Drummond, Clark, & Moore, 2005).

However, alcohol is metabolized very rapidly, typically at the rate of one glass of wine

or about 8 oz of beer for 1 h. After several drinks, alcohol is fully metabolized

by the body about halfway through the night resulting in shallow, broken sleep with

increased REM (dreaming) sleep in the latter portion of the night (Gillin et al., 2005).

In some individuals, sleep may be disrupted by stomach irritation, a full bladder,

rebound wakefulness, sweating, or nightmares. Thus, whereas alcohol often makes

it easier for the insomnia sufferer to fall asleep, sleep maintenance and overall sleep

quality are usually disrupted resulting in an overall compromise of the total

sleep period.

Alcohol has a number of side effects and risks associated with both its short- and

longer-term use. In the short run, alcohol tends to increase the likelihood of snoring

and apneic (i.e., breathing pauses) episodes even in those without any history of

sleep apnea (Dawson, Lehr, Bigby, & Mitler, 1993). If alcohol is used routinely,

tolerance usually develops resulting in the need for dose escalation to obtain con-

stant subjective effects. In addition, alcohol is associated with considerable risk for

dependence. If dependence does develop, the alcohol user typically reports diffi-

culty sleeping without a drink. With prolonged use of alcohol, daytime hypersom-

nolence and cognitive dysfunction may be observed. Individuals who develop

alcohol dependence often show marked sleep disruption upon becoming abstinent.

Moreover, heavy and long-term users often show continued disruption of sleep even

1–2 years after becoming abstinent (Brower, Aldrich, Robinson, Zucker, & Greden,

70

5 Medication Considerations

2001; Gillin et al., 2005). Thus, despite its popularity as a sleep aid, alcohol cannot

be recommended to address insomnia.

Can Common Anxiety Medications Cause Insomnia Symptoms?

Many individuals with anxiety disorders receive some form of pharmacotherapy as

treatment for their anxiety symptoms. Currently, the two classes of prescription

medications that are commonly used to treat anxiety disorders are the serotonin

reuptake inhibitors and the benzodiazepines. Included in the former group of com-

pounds are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine,

paroxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, citalopram, and escitalopram. Also included in

this broad class of medications are the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake

inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine. Included in the latter class of medications

are such substances as diazepam, lorazepam, and clonazepam. As both of these

types of compounds can have effects on sleep or wakefulness, it is useful to con-

sider those effects here.

Whereas SSRIs and SNRIs are often considered the first line pharmacologic

agents prescribed for managing anxiety symptoms, these medications can have

negative effects on sleep and wakefulness. All of these medications may induce

insomnia. In fact, the rate of treatment-induced insomnia ranges from a low of

about 5% with escitalopram to as high as 22% with fluoxetine (Schweitzer, 2005).

Likewise, these medications may result in daytime sedation with such symptoms

occurring in 0–5% of all patients treated with escitalopram and slightly over 20%

of those treated with fluoxetine or paroxetine (Schweitzer, 2005). Thus, with

patients receiving an SSRI or SNRI report insomnia and/or over sedation in the

daytime, the possibility that such symptoms relate to their antianxiety agents should

be considered, particularly when such symptoms emerge after treatment initiation.

Benzodiazepines such as diazepam, lorazepam, and clonazepam are commonly

prescribed for the management of anxiety disorders. These medications may be

administered to manage daytime anxiety symptoms and/or at bedtime if insomnia

accompanies the anxiety symptoms. The benzodiazepines mentioned all have such

properties as tolerance and dependence with continued use (Greenblatt, 1992).

Generally, insomnia does not develop during periods of active use but may develop

upon abrupt withdrawal, particularly if such medications are typically taken at

bedtime to manage insomnia symptoms. This withdrawal effect is likely to be

most pronounced with lorazepam, given its short half-life, but insomnia may

develop upon withdrawal of the other medications mentioned as well (Greenblatt,

1991; Sironi, Miserocchi, & De Rui, 1984). Daytime sedation/drowsiness may

result from these medications with such effects being more likely and pronounced

with the longer acting agents (e.g., clonazepam) as opposed to the shorter acting

ones (e.g., lorazepam). Other side effects common to these agents include impaired

motor coordination, dizziness, impaired learning, anterograde amnesia, agitation,

and depression.

Combining Sleep Medications with CBT for Insomnia

71

Combining Sleep Medications with CBT for Insomnia

Sleep medications are so widely available and well publicized that many who seek

out cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy have either used such medications or at

least considered their use. As noted previously, many who begin CBT for their

insomnia present on one or a combination of sleep medications, both prescription

and over-the-counter preparations. These patients may ultimately want to discon-

tinue their sleep medications entirely but are not ready to do so at the time they

enter treatment. Others may not wish to stop using their medications at all but

desire additional nonmedicinal intervention for sleep. Usually, a strong psychologi-

cal dependence on sleep medications has developed and such individuals feel

unable to sleep without them (Belleville, Guay, Guay, & Morin, 2007; Lichstein

et al., 1999). Such individuals may overvalue the effectiveness of their sleep medi-

cations and lack confidence in their ability to sleep without them (Belleville et al.,

2007). Moreover, compared to insomnia sufferers without medication dependence,

there may be a greater degree of unhelpful beliefs about their insomnia and notable

pessimism about their ability to gain control over their sleep (Carney, Edinger,

Manber, Garson, & Segal, 2007). Given these observations, it seems reasonable to

assume that they could be relatively difficult to treat with strategies such as CBT.

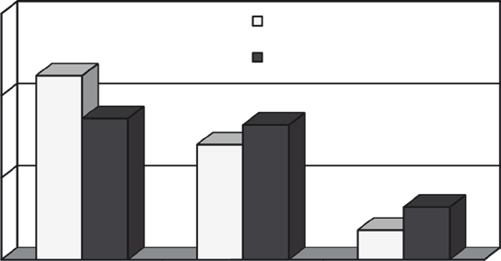

Despite this concern, the data available tend to suggest that such people can and

do benefit from CBT for their insomnia problems. In fact, most studies that have

examined the relative responses of those who enter treatment on and off hypnotic

medications tend to show that hypnotic use does not necessarily dampen CBT treat-

ment response (see Morin et al. 2006 for recent review). Typical of such findings

are the data shown in Fig. 5.1. These data derived from a large (

n

= 127) case repli-

cation series study (Verbeek, Schreuder, & Declerck, 1999) of those treated with

CBT showed no difference in the global treatment responses of hypnotic users and

nonusers. Similarly, in two large effectiveness studies, Espie (Espie, Inglis, Tessier,

& Harvey, 2001; Espie et al., 2007) found that patients who used hypnotics on a

chronic basis were no less likely to respond to a nurse-administered CBT insomnia

intervention delivered in primary care settings than were those patients who were

medication free. Although at least one small (

n

= 21) uncontrolled trial (Backhaus,

Hohagen, Voderholzer, & Riemann, 2001) suggested that medication-free patients

respond better to CBT than do those who are hypnotic dependent, this finding

appears contrary to most CBT studies that have conducted post-hoc comparisons of

such groups. Thus, given most current evidence, it seems that a history of hypnotic

medication use should not be considered as a contraindication or limiting factor

when considering people for insomnia treatment with CBT.

A slightly different set of considerations arises when determining whether hyp-

notic medications should be used in combination with CBT to enhance insomnia

treatment outcomes. Rationale for such a treatment combination derives from con-

sideration of the relative advantages and disadvantages of each of these two treat-

ment modalities. Hypnotic medication has the advantage of producing immediate

sleep improvements usually on the first night of administration. However, all hypnotic

72

5 Medication Considerations

Subjective Improvement Ratings

75

Medication Free n = 34

56

Hypnotic Users n = 49

50

ple

43

41

35

of sam% 25

16

9

0

Good Outcome

Reasonable

No Change

Outcome

Good Outcome

= improved sleep + improved daytime function +

able to cope with sleep problem

Reasonable

= Improvement in at least 1 of these 3 areas

No Change

= no perceived improvement

Fig. 5.1

Response of hypnotic users & nonusers to CBT (Verbeek et al., 1999)

agents carry some risk for at least psychological dependence with their long-term