Imperial (97 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Sources:

California Board of Agriculture (1918) for 1910; Imperial County Agricultural Commissioner’s papers (1920); Imperial Valley Directory (1930); Otis B. Tout (1931); Imperial Valley Directory (1939); Imperial Valley Directory (1949); California Board of Equalization (1949); California Blue Book (1950).

At the beginning of this period, total acreage in the county approximately doubled. The number of farms stayed constant at less than forty-eight hundred, which I interpret as good news for local farmers: It would seem that they did not sell out and were able to increase their holdings. Of course their expansion would have increased their dependence on hired field labor; in other words, it would have facilitated

the divorce of ownership from management.

In 1934, the Dean of Agriculture at University of California, Berkeley, visits the Imperial Valley and writes in his personal notes:

Sharp Reduction in acreage 67% of valley absentee land owners.

In 1942, the first year of All-American Canal water, the Bureau of Agricultural Economics concludes:

About 40 percent of the total number of farm owners do not live in the valley but collectively control almost one-half (48 percent) of the total acreage in farms . . .

Here’s another statistic which bodes poorly for the family farm: By 1940, only forty-five percent of Imperial County’s workforce engages in agriculture.

The extreme fluctuations in the number of farms shown in the table disturb the imagination. The change between 1944 and 1945 is especially distressing, implying defaults, foreclosures and abandonments—unless, of course, one or both of the figures for those two years was bogus. In any case, most commentators draw sharp conclusions. An essay on the All-American Canal opines that the lure of Colorado River water brought speculators and agribusiness managers to the Imperial Valley, causing it to be

populated by a small handful of owners and operators at the top of the social pyramid and a great lower class of workers, mostly of Mexican origin . . .

In other words, there are many who do not know they are fascists but will find out when the time comes. Another historian writes:

It did not take long for the Imperial Valley, eventually subsidized by the reclamation-built All American Canal . . . to become dominated by the same landowner class already present in 1900 when Harrison Gray Otis and his partner Moses H. Sherman purchased a 700,000-acre ranch adjacent to the Imperial Valley, and extending into Mexico.

Here is one last opinion:

From the first years of settlement to the present,

runs a book called

Salt Dreams, the average size of Imperial Valley holdings steadily increased.

What its authors make of that statement we shall see when we look in on farm size once more, during the latter half of the twentieth century. For now, let us stay in the Depression years.

In those days,

172

I asked Edith Karpen, who owned the farms in the Imperial Valley?

Mostly, Americans owned the farms. At that time you could hardly make a living because they had field crops. Most of them had a section—six hundred and forty acres.

So a hundred and sixty acres wouldn’t have been enough? I’ve read about that hundred-and-sixty-acre limitation.

Oh, no. You couldn’t have made ends meet.

“THEY PUT UP THE RED FLAGS”

In Mexican Imperial, the case was rather different. Harry Chandler was about to lose his empire of acres!

We have seen that even the Zapatistas, who were among the most radical elements of the early Mexican Revolution, considered the

ejidos

less as utopian vehicles of redistribution than as the restoration of hoarded land titles dating from the Conquest. In Zapata’s zone, progressive young land surveyors consulted elders in order to mark the traditional borders of village holdings. Zapata did eventually seek to dispossess haciendas of certain lands to which no village had ever asserted a claim, but it was with the caution of a de Anza in hostile desert that he proceeded beyond his premise of restoring prior legal rights.

Much of the Mexicali Valley had not been irrigated or cultivated before the Colorado River Land Company got there. No matter; Mr. Chandler’s prior rights did not count. Nor should they have; his company disdainfully disregarded Mexican-ness. In 1927, for example, even as the Peasant Union of two Mexicali

colonias

ominously petitioned to expropriate thirty-five thousand of its acres the company had proposed

to bring hundreds of thrifty ranchers from Germany and Central Europe

into the place that it liked to call

Mexican Imperial Valley.

Two hundred thousand acres would be subdivided into parcels of thirty, forty and more acres for these Europeans. Thus, the Colorado River Land Company was ironically promoting small, relatively egalitarian landholdings, perhaps because it saw the revolutionary handwriting on the wall. Meanwhile, by an odd coincidence, the company’s manager, H. H. Clark,

has the distinction of being the world’s largest cotton rancher.

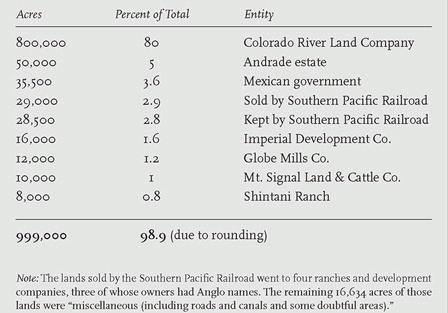

The table on page 576 gives some indication of Mr. Clark’s supremacy.

An additional cause of the hatred so many Mexicans felt toward the Colorado River Land Company had to do with the local grantees of its leases. In 1924, for example, its ninety-five

protocolized leases

consisted of the following: fifty-six to Chinese, twenty-two to Japanese, nine to Mexicans and eight to Americans. One report to stockholders opined that Chinese worked harder to improve their parcels than did any white man. Whether or not that was so, Mexicans felt not merely oppressed by the situation, but insulted.

Chandler repeatedly expressed his intention of subdividing Mexicali Valley lands and selling them to colonists. Why then did he continue to lease them out, thereby inflaming campesinos against him ever more year after year? In part, I am sure, his congenital opposition to organized labor would have left him cold to peasant demands. A second reason was that if he could ever finish his cotton railroad to the sea, and irrigate the valley more grandly, he could fetch a higher price for his properties—hurrah for the Ministry of Capital! Finally (and here I almost feel sympathy for him), since the Revolution prohibited most foreign ownership of Mexican land, particularly in those politically sensitive areas near the border, Chandler and his partners worried that if they did sell, only Mexicans would be legally allowed to buy, not those

thrifty ranchers from Germany and Central Europe;

and should the unthrifty Mexicans default on their mortgage payments, the company, whose title survived only through an increasingly precarious grandfather clause, might not be able to repossess the land.

LAND OWNERSHIP IN THE COLORADO RIVER DELTA,

ca.

1930

Source:

Otis P. Tout (1931), citing a Congressional report.

This was why Chandler fantasized about selling to Italian immigrants, or English, or even the hated Chinese and Japanese. The Pueblo Brant subdivision of 1926, which he magnanimously planned to offer to Mexicans who had gained their farming experience on the northern side of the ditch, was too little and definitely too late, because by then the land invasions of hungry campesinos had already begun.

In 1924, the Colorado River Land Company was pressured into developing infrastructure in the Mexicali Valley in exchange for retaining most of its land titles. The pressure continued. By 1930, although the company

remained the dominant economic force in Mexicali Valley,

it was four million dollars in debt and still had not yielded any dividends. In 1936, a convenient new American syndicate called the Chandler-Sherman Corporation sued that Mexican entity, the Colorado River Land Corporation, for recovery of moneys lost by such stockholders as Harry Chandler, winning a four-million-dollar judgment. I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life. That was just as well for Chandler, because expropriation was coming ever closer.

By 1937, the All-American Canal had nearly been completed. The Imperial Canal would soon go dry, and with it much of Harry Chandler’s utility to Mexico, for the rights to half the water in the old canal—which is to say almost all of the water in the Mexicali Valley—would now be the rights to nothing. For years, Chandler and his

Los Angeles Times

lobbied Northside not to set aside those rights. They had lost that battle. Now Mexico must soon find other water from other ditches. Hoping to establish a case for herself under the Northsider legalism of prior and beneficial water use,

173

Mexico now wished to finish settling and irrigating the valley immediately, before the All-American Canal was finished.

And where were her settlers? They kept coming. They could not afford to rent parcels from the Colorado River Land Company, let alone buy land. In 1930, some campesinos whose attempted legal expropriation of Chandler’s fields for

ejidos

had failed remained as squatters. They were jailed. Among them we find the charismatic devotee of agitprop Felipa Velázquez, then forty-eight years old. Her watch-word:

We are going to fight, no matter what happens.

When they arrested her and her children, the

agraristas

were performing an anti-capitalist play by Ricardo Flores Magón, who you may remember had been a leader in the movement that briefly seized Mexicali in 1911. The detentions caused such a stink that after five months the land-invaders were released. Meanwhile, Baja’s territorial representative in Mexico City demanded the revocation of the Colorado River Land Company’s legal title. A manifesto of the Bar and Restaurant Employees Union in Mexicali cried out

from our very soul that Mexico is for the Mexicans . . .

but

the heart of the city is owned especially by chines, japanese and jews

[

sic

]—in other words, Chandler’s preferred tenants. Seeing where the winds blew, Chandler tried to sell off his lands before they were simply seized. In 1936, he signed a colonization agreement with the Cárdenas government. The Colorado River Land Company promised to finish surveying its holdings and sell them off over twenty years.

Almost immediately afterward, Cárdenas intimated that these transfers ought to occur in five or six years, not twenty. Chandler must have been furious. As it turned out, Cárdenas was a moderate, for the field workers of the Mexicali Valley now took over. Among their leaders were many of the campesinos who had been arrested with Felipa Velázquez.

As 1937 began, a committee of campesinos petitioned once again to carve their own

ejidos

out of the company’s parcels. They demanded arms. While the authorities hesitated, four hundred of them occupied Chandler’s fields and expelled the paying tenants—most of whom were Chinese, of course, so to the

agraristas

they did not count.

One very hot afternoon, Yolanda Sánchez Ogás, to whom this book is so indebted in regard to Chinese tunnels and Cucapá Indians, was in a car with me, en route to a filthy barracks in Ejido Tabasco where some campesinos had recently been living, as she said, like slaves, and when I asked her to tell me the tale of the

ejidos,

she said:

We kicked out Díaz in 1910,

174

but there were still plantations until 1937. We tried many times to get rid of the Colorado River Land Company, but in ’36 here and in Nayarit, our agrarian groups finally got together. They made different ranches. There were five different agrarian committees that formed a federation. They took the land they worked. They didn’t use weapons, but they put red flags around ranches and said:

This land is ours,

because they knew that President Cárdenas would support them. On 27 January 1937 they put up the red flags in our valley. The Colorado River Company had White Guards;

175

their job was to prevent campesinos from organizing. The company had arrived in the valley in 1904. They preferred to rent land only to Chinese, Japanese and Americans, not to Mexicans, since Mexicans possessed real rights to the land.

So the White Guards and soldiers came, she continued. They put many campesinos in prison. The prisoners sent a telegram to Cárdenas. The Secretary of Agriculture came fifteen days later. And they formed the first

ejidos.

Were all the fields the same size?

Here in Baja California, on account of the desert climate, the

ejido

land parcels had to be twenty hectares. (At first, they were much smaller, some as little as four hectares.)

176

There might be forty people in one

ejido,

a hundred in another. But each had a parcel. The government did this to get settlers up here. Even Americans came, but—Yolanda smiled—they

left.