Imperial (96 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Chapter 97

FARM SIZE (1910-1944)

Our economy is based on the exchange of goods and services through the medium of money . . . Thus farming for the market gradually became the predominant pattern for successful agriculture.

—Frederick D. Mott, M.D., and Milton I. Roemer, M.D., M.P.H., 1948

O

f course everything was slow then; but everything was also enlarging. The property rectangles on the early Imperial County Assessor’s maps respect at least the spirit of the Reclamation Act: The large parcels outweigh the small to no obscene degree; and many farmsteads remain identical in size.

There is no escaping the stereotype of an ideal agrarian world.

But Emersonian dreams, no matter how passionately syndicates and realtors invoked them, rapidly grew more phantasmal in an America where between 1910 and 1940, the proportion of farms five hundred acres and larger rose from twenty-eight to forty-five percent! In 1939, a utilitarian calculated that the gross income which a farmer needed to survive was fifteen hundred dollars; only one farm in five achieved this minimum. Although poor crop yields, low prices, etcetera, might well impoverish large farms more than small, on balance the former had a better chance . . .

But never mind the rest of America.

My vision beholds the greater Imperial Valley of thirty years hence, then as now conceded the most productive agricultural area in the world.

Why shouldn’t the Wilfrieda Ranch prosper forever?

In 1940, Ernest Hemingway’s

For Whom the Bell Tolls

introduces us to the fascinatingly date-specific concatenation of a good American from Montana who has placed himself under Communist discipline in order to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The guerrillas ask him whether in his country land is owned by the peasants. He replies:

Most land is owned by those who farm it. Originally the land was owned by the state and by living on it and declaring the intention of improving it, a man could obtain title to a hundred and fifty hectares.

Tell me how this is done,

says one of his interlocutors.

This is an agrarian reform which means something.

Robert Jordan, bemused by the notion that this is an agrarian reform, explains that this is simply

done under the Republic.

In other words, it is American, plain and simple.

They ask him about large proprietors and he expresses the guarded hope that

taxes will break them up.

They inquire whether there are many Fascists in his country and he replies:

There are many who do not know they are fascists but will find out when the time comes.

Poor Robert Jordan! No wonder that his creator makes him die with noble uselessness for a doomed cause! Here in the agrarian paradise called Northside, farms keep right on getting larger and fewer.

MIDAS’S HELL

Wilber and Elizabeth Clark had been among the last generation of homesteaders in the continental United States. Between 1900 and 1918, California’s vacant public lands shrank from forty-two and a half million to twenty and a half million acres. In 1920, when Imperial still boomed north and south of the line, the United States Department of Agriculture Yearbook bravely confessed the inevitable:

We have always been able to look beyond the frontier of cultivation to new and untouched fields ready to supply the landless farmer with a homestead . . . That untouched reserve has about disappeared.

Never mind, my fellow optimists; we need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by; because we possess a new reserve: the potential yield of science and efficiency! In fact, we have just now achieved nearly the largest harvest in American history; our corn crop alone equals more than eighty percent of world production!

To a family farm ensnared in the money economy, this accomplishment is catastrophic. If we produced only for ourselves, doing our own work,

168

and could be satisfied with that, we might have been happy. Unfortunately, people have a way of wanting washing machines, movies and store-bought dresses. And even if everybody on the farm could somehow resist the lure of a commodity produced by someone else, by now we’ve found ourselves assessed for various social services unknown to Wilber Clark. One source from the mid-1940s lists road districts, reclamation districts, drainage districts, pest-control districts, all presenting their obligatory invoices on top of the irrigation district charges without which Imperial would return to salty silt. This financial burden on farmers is significant, increasing and non-negotiable.—Never mind; we live in the greatest democracy on earth; that means we pay those bills because we

want

to; roads and pest control benefit us, so how could we not love to do our part?—In any event, these “wants” invite us to produce as much as possible in order to maximize our power to fulfill them. Therefore we become vulnerable to the conditions of our time: shocking price jumps for the fertilizers and machines to which we’ve addicted ourselves, and shrinking reservoirs of willing farmhands. This latter scarcity not only (as Marx would say) commodifies labor but also makes it more expensive. (Thank God for Mexicans!)

Altogether, in the spring of 1920 the American farmers were confronted with the most difficult situation they had ever experienced.

Our only hope of paying these new costs is to produce even

more.

Since our neighbors follow the same logic, and supply lowers demand, we drown in our own golden harvest!

169

The crop of 1920 is accordingly

worth, at current prices,

three million dollars less than the previous year’s, even though the latter was smaller, and a million less than the year before’s, which was smaller still.

Call this foreseeable. Back around the time of the Mexican War, Thoreau had cast his Olympian pity upon any farmer who strove for more than subsistence.

To get his shoestrings he speculates in herds of cattle. With consummate skill he has set his trap with a hair spring to catch comfort and independence, and then, as he turned away, got his own leg into it.

And so Thoreau escaped poverty by doing without the supposed necessities of the poor—for instance, their coffee. His sojourn at Walden Pond is instructive—not least because he declined to remain there. And so, although the crisis of family farms was indeed foreseeable, it was also inevitable. Even one of Southside’s greatest (because stubbornest) agrarian revolutionaries, Emiliano Zapata, who rose up against the encroachments upon village land of the sugarcane haciendas, and fought year after year to safeguard the

ejidos

of Morelos, counseled his neighbors to exceed mere subsistence, because it sometimes wasn’t even that:

If you keep on growing chile peppers, onions, and tomatoes, you’ll never get out of the state of poverty you’ve always lived in. That’s why, as I advise you, you have to grow cane . . .

Rich or poor, we human beings continue most faithfully to set our traps to catch more comfort and independence. We’ll sell out at a fancy price.

All is relative, to be sure; the difficulties of American farmers in 1920 compare paradisiacally to those of their counterparts in the Revolution-razed Mexico of 1915, when Zapata uttered the words just quoted, but that gives us no right to trivialize Northside’s desperation. What should the farmers do? They can go to market in cooperatives and associations, as the citrus ranchers did.—In 1905, D. D. Gage,

a prominent citizen in Riverside,

came home from the East and advised his fellow orange growers that

the salvation of the industry lies with the big department stores of the great cities.

(The Safeway Farm Reporter knew all that.)—Unfortunately, the big department stores won’t stock Imperial’s alfalfa, but maybe some middleman could peddle it away. And wouldn’t it be fine if that middleman were somehow accountable or beholden to the growers? Perhaps, in other words, American farmers can survive being assimilated into an economic superorganism through the expedient of superorganizing themselves. Who knows? This is about all that the Department of Agriculture can advise.

In time, the farmers will accept this logic. That 1958 hearing on the proposed marketing order for winter lettuce is evidence of that. Rival entrepreneurs that they have become, they remain nonetheless united in their bafflement before the common problem. Norman Ward, sales manager for Farley Fruit in El Centro, remarks that both lettuce and cantaloupes remain in eternal oversupply. He refers to

a terrible glut from which we can never dig out.

“THE DIVORCE OF OWNERSHIP FROM MANAGEMENT”

California held a hundred and fifty thousand farms in 1940—only two point two percent of all farms in the United States, but thirty-six point seven percent of all large-scale farms.

170

The Department of Agriculture concluded:

The tendency toward larger farms is likely to throw an almost insurmountable barrier in the way of a man who wishes to progress up the so-called agricultural ladder . . . The divorce of ownership from management tends to eliminate the small-scale producer, and hastens the development of a group of rural people who have no property and must sell their labor in order to live.

In this respect, the California of 1940 was moving in the direction of the Mexico of 1540. Again, it goes without saying that even in the worst Depression years, California’s homesteaders never got dispossessed as indigenous Mexicans had been by the conquistadors (or indigenous and Mexican Californians by the Anglo-Americans); but the process, however attenuated in American California, and however different in its cause—capitalist concentration, not foreign expropriation—was similar. Cortés had made a habit of bestowing captured Aztec towns on his conquistadors; this scheme was called the

encomienda.

The town’s owner got Indian tribute and labor. We read of a colonist

of the northern frontier,

a zone approximating Imperial, who assembled a Chandleresque domain of 11,626,850 acres. Three and a half centuries later, while the haciendas enlarged themselves under the benign eye of President Díaz, the

encomienda

reinvented itself, complete with a company store. In twentieth-century American Imperial, the longterm trend toward average acreage increase, combined with population growth, logically reduced the ratio of owners to tenants. Is tenancy necessarily a state of exploitation? That is not for me to say. But it is evidently a less secure state than ownership.

Steinbeck’s

Grapes of Wrath

was about Okies. California had her own Okies. So did Arizona. In 1927, just a few miles east of the entity I call Imperial, in the neighborhood of Yuma, a child was born to a Mexican-American family who soon lost their statutory hundred and sixty acres. That child was the future farmworker organizer César Chávez. Meanwhile, in Imperial County itself, by 1930 almost three thousand of the forty-seven hundred farms in existence were operated by their tenants, not their owners. In other words, a shocking three-fifths of the county’s farms were no longer, if they ever had been, self-sufficient family homesteads.

(In a Dorothea Lange photograph from the Imperial Valley, a former tenant farmer now on relief leans slightly toward us, his eyes narrowed in what is probably a habitual squint although the shiny pupils and the clenched grimace bestow on him the distinction of anguish. The year is 1936.)

In 1910 there had been only thirteen hundred and twenty-two farms in Imperial County. Fifty-one of them comprised less than three acres, ten were owned by petty Harry Chandler types, being a thousand acres and over;

171

four hundred were in the bailiwick of the old limitation law: a hundred to a hundred and seventy-five acres. By 1913, certain large-scale Imperial Valley cotton growers had already leased cotton hectares from the Colorado River Land Company. A year later, the Chandler Syndicate, in cahoots with

a number of Los Angeles business and professional men,

was preparing to grow citrus on Imperial Valley parcels of forty to six hundred and forty acres apiece.

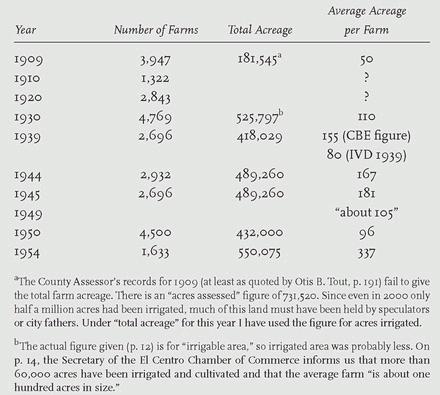

The numbers I possess simplify this complex situation. They seem to show that between 1928 and 1950, average acreage increased from a hundred and ten to a hundred and eighty-five acres per farm—no more than average California acreage, and probably less. But the unreliability of the data must be emphasized; for example, note that the 1950 entry in the following table is not exactly a hundred and eighty-five acres. All we can say for certain is that the general tendency of average acreage is

increase.

AVERAGE ACREAGES OF FARMS IN IMPERIAL COUNTY

The Reclamation Act of 1902 fixed a 160-acre homestead limit, 320 acres for a married couple. By 1918 the homestead limitation had been adjusted to 320 acres for an arid homestead and 640 acres for cattle lands without a watering hole.