I'm Just Here for the Food (4 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

When it comes to the actual act of seasoning there are a couple of things to keep in mind:

• Salt all dish components separately. Just because you salted the dressing doesn’t mean you shouldn’t salt the greens.

• Salt should be added when it can do the most good: during or even before cooking. Liberally salt the water the potatoes cook in and they will be properly seasoned. Wait to season them at the table and you’ll have flat-tasting potatoes covered in little rocks. In some cases salt can be added well before cooking, while in others it should be added just before.

FOR THE RECORD

•

Salt is mentioned more times in the Bible than any other food.

•

The word salary derives from the Latin word for salt and refers to the money Roman soldiers were paid specifically for the purchase of salt. Thus, to be worth your salt is to earn your pay.

•

The French Revolution began as a protest against the

grabelle,

a salt tax.

•

Salzburg means “salt castle.”

•

In Leonardo da Vinci’s

The Last Supper

, Judas is seen spilling salt, a symbol of betrayal.

•

In Arab lands, the sharing of salt implies an unbreakable bond.

•

In some European societies, salt is thrown over one’s shoulder to hinder the devil, who’s always sneaking up on you.

•

Before mechanical refrigeration was available, salting was the leading method of food preservation.

IODINE AND SALT

If the human machine doesn’t get enough iodine, the thyroid gland gets mad. Then it gets even by getting big and sprouting cysts, which give the unlucky victim the neck of a bullfrog in mid-croak. Although you’re not likely to spot a goiter while strolling through your local mall, there was a time when goiters were a common sight. In the early days of the twentieth century, goiter reached epidemic levels in the Midwest. The fix was to add iodine to something of universal use: salt. The problem deflated overnight. Actually, the best source of dietary iodine is seafood and since it’s a lot more available than it used to be it’s tough to find a good goiter . . . unless you travel to Africa, Asia, or parts of South America.

ME: I often season meats several minutes before cooking them.

YOU: Eeek. Don’t you know that pulls juices out of the meat?

ME: Yes.

YOU: (stunned silence)

ME: Coaxing fluids to the surface of meat is not always a bad thing, especially if those fluids contain water-soluble proteins and the meat is headed for the searing pan. When they come into contact with high heat, these proteins contribute to the browning process.

CHEMICALLY SPEAKING: SALT

Any time you find an acid bound to an alkaline, you’ve found yourself a salt. Of course, in the kitchen we’re really only concerned with NaCl, the molecular marriage of chlorine (an acidic gas) and sodium (a base metal). If you’re into curing meats you might also be into sodium nitrite or perhaps even sodium nitrate. The two elements are united by an ionic bond, which means they’ve got one of those license plates that reads “2gether 4ever”—this is one of the strongest bonds around.

Different types of salt taste different not because of differences in the salt per se but because of the other stuff they’re mixed up with.

Artisanal sea salt

, for instance, raked right off the beach, contains traces of salts other than NaCl, not to mention a host of other minerals.

Rock salt

, mined from the ground, can contain anything from iron to cobalt (a good reason to restrict its use to endothermic reactions). Most of the salt sold in the United States is very nearly pure, because it’s harvested as a brine. Water is pumped into solid underground salt reserves, which then dissolve and are pumped back to the surface. The brine is stripped of other components (usually by physical rather than chemical means) and then concentrated by boiling. The brine is then cooled until tiny, perfect cubes of salt are forced out of the solution. Before these are marketed as

table salt

, they have a couple of things added to them: anticlumping agents and iodine (see Iodine and Salt).

If the brine is boiled and cooled in open pans, conglomerates of crystals grow downward from the surface like upside-down pyramids. These are separated out via centrifuge, then dried and sorted by size. The larger pieces (which may be rolled into flakes) are sold as coarse or

kosher salt

.

Kosher salt tastes better on food. The fact that kosher salt doesn’t contain any additives may be a factor, but I suspect it has more to do with timing. Because kosher salt flakes are irregularly shaped and have a very low surface-to-mass ratio, they dissolve slowly, releasing their flavor like a time-release medicine. The tiny cubes of table salt attack the tongue all at once. I can always tell when food has been sprinkled with table salt because salt is the first thing I taste. Kosher salt works more behind the scenes and is therefore (to my tongue at least) a more effective seasoning.

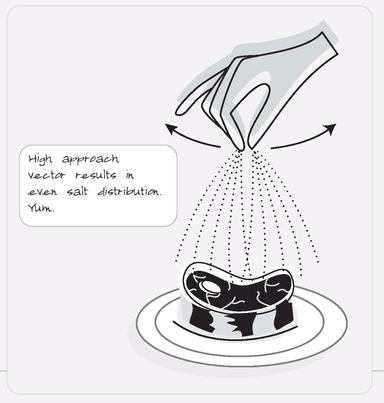

Even if flavor weren’t an issue, I’d still prefer kosher to table salt because it is controllable. Since it’s composed of irregularly shaped flakes, you can actually pinch kosher salt between your fingers and hold it there. Gently move your fingers back and forth and the flakes gently fall. Stop moving and the salt stops falling. Table-salt crystals are so small and so uniform they tend to act more like a fluid than a solid, so even if you manage to get hold of a few, you’re not going to get to decide where they go. Although kosher flakes are quite large, the crystals that make them up are actually very fine, so when a flake of kosher salt hits the moist surface of a food, it dissolves quickly and spreads out across a wider area.

The only other salt I keep around is Danish smoked salt, a finishing salt (as opposed to a cooking salt) that is made from sea water cooked down over alderwood fires. The crystals are as brown as Demerara sugar. Sprinkled on a steak . . .well, it’s good.

THE SPICE KING

Black pepper is the king of spices. Back in the Middle Ages, pepper was a currency: a family’s wealth was determined not by how much money they had in the bank but by how many peppercorns they had in their pantry. Black, white, and green peppercorns all come from a small berry that grows in clusters on a vine native to India. When these berries are picked young, dried, and fermented, they become black peppercorns, whose hot spice is tempered by a touch of sweetness. White peppercorns are mature berries that have been dried and rubbed from their skins. They are less pungent than darker pepper. Green peppercorns are brined or freeze-dried and have a slightly sour character, similar to capers. Whole peppercorns can be stored up to a year in a cool, dry place, but their essential oils disperse quickly when ground, so use a pepper mill rather than a pepper shaker. (For more on spices, see

Spice Rubs

.)

CHAPTER 1

Searing

The fastest way to get heat into food short of dipping it in hot lava...tastes better, too.

King Sear

This method creates a flavorful brown crust on the surface of many foods, the mere mention of which has been proven to activate saliva production in human test subjects (a fact not lost on the food service industry). What searing does not do is “seal in flavors” or “seal in juices.” If you feel it necessary to seal in juices you should buy a laminator.

HERE’S WHAT YOU NEED

A source of high heat. The average electric cook-top coil tops out at 2000° F. A gas flame—my personal favorite—can reach 3000° F. Searing can also be executed in a pan on the floor of a hot oven or on the exhaust manifold of a Formula One racing car (yes, it’s been done).

A perfect vessel

Not only does the ideal searing surface (pan, skillet, and so on) have to get very, very hot, it has to get evenly hot all over and it has to be able to maintain that heat even in the face of foods. Several materials are ruled out from the get-go. Wood and paper make lousy searware because they tend to become fuel before they get hot enough to actually sear anything. Glass and ceramics are such lousy conductors of heat that they’re called “insulators.” Come to think of it, all the really great heat conductors are also great electrical conductors and they’re all metal. What’s so special about metals? Besides the fact that they can be molded, cast, and forged, they have a unique, crystal-like molecular structure. The atoms are locked in a uniform geometrical pattern, which makes metals (except mercury) pretty darned tough to bend or break. But their outer electrons are so weakly bound that they just wander around throughout the surface like quantum Flying Dutchmen, which is exactly what makes metals such good conductors. So when the electrons meet the heat on the bottom of the pan, they vibrate through to the other side, thus conveying the hot stuff to the cool stuff. Of course, this leads to the question: Which metal sears the best?

Copper

is the hands-down winner when it comes to conductivity—that’s why we make wire out of it (that, and the fact that it’s easily extruded). Trouble is, purchasing copper cookware often requires taking out a small loan. And since copper is toxic in large amounts it has to be lined with either steel or tin, which tends to wear off. Save copper for where it’s really needed: a bowl (see

Reactivity

).

Aluminum

is also a righteous conductor. It’s economical and it’s light, but that’s a problem, because being light it lacks the density to hold a lot of thermal energy. That means it’s going to need some recovery time when something cold comes to call. Aluminum also reacts chemically with certain ingredients and eventually warps, so I’d skip it altogether.

Stainless steel

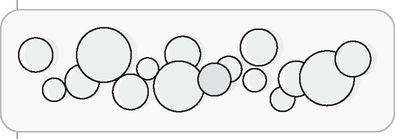

is bright and shiny, durable, relatively inexpensive, and relatively easy to clean. Did I mention that it’s bright and shiny? But it’s not a great conductor because it’s an alloy, a mixture of several metals. And that means that instead of a neat and tidy molecular structure it looks something like this:

This makes it tough for electrons to get around. I still think stainless steel makes a swell sauté pan, but for searing I’ll hold out for iron.