I'm Just Here for the Food (14 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

Heat the broiler and position the rack to about 5 inches below the heat source. Arrange the shrimp in the broiler pan so there is no overlapping. Drizzle the oil and scatter the garlic over the shrimp and season with salt, pepper, and Old Bay. Put the pan under the broiler for 2 minutes, until the shrimp begin to turn pink. Sir in the lemon juice, add the panko and parsley, and toss to coat the shrimp evenly. Return to the broiler and cook until the bread crumbs are evenly brown. Serve immediately.

(Alternatively, sauté the shrimp in the oil and garlic and, when they are almost finished, season with salt, pepper, and Old Bay and deglaze the pan with the lemon juice and toss in the panko and parsley. Cook just until the shrimp are done. In my experience, this is the way you’ll find the dish prepared in most restaurants, but broiling is the classic method and gives a much better flavor and texture.)

Yield: 2 entrée servings or 4 appetizer servings

Software:

1 pound peeled and deveined large

shrimp

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 tablespoon minced garlic

Kosher salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Old Bay seasoning

4 tablespoons freshly squeezed

lemon juice

¼ cup panko (Japanese bread

crumbs)

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

Hardware:

Broiler pan

Shallow glass baking dish or an

ovenproof sauté pan

SHRIMP SMARTS

When shopping for shrimp, focus on numbers, not labels. Shrimp are sized and sorted into count weights. The higher the number, the smaller the shrimp: 50/60 means 50 to 60 tails per pound. The largest shrimp have a “U” before the number, signifying that there are fewer than that number per pound: U/12 means that there are 12 or fewer shrimp per pound. Though they serve as rough guidelines, labels like “jumbo” or “medium” aren’t very telling, as they’re not standardized.

CHAPTER 3

Roasting

If dry cooking methods were the Beatles, roasting would be George Harrison. Quiet, but effective.

Roast Story

Had Pavlov gone to a few wedding receptions or hung out at a brunch buffet or two he might not have had to measure up spaniel spit. His theories regarding conditioning could easily have proven themselves at the carving station. I’ve worked the carving station and I don’t care if it’s a steamship round, a loin roast, a standing rib roast, or a charred buffalo head, flash some golden crust and a little rosy pink flesh and the culinary tractor beam engages. It’s like a bug zapper for humans. I believe this auto-response has as much to do with ancient associations as it does with flavor. Think about it: when do we roast turkeys? When do we roast standing ribs? What’s at the end of the line at the wedding reception? That’s right: roast beast. Where there is roast, there is a gathering. Done right, there is also a lot of satisfaction—not to mention enough leftovers for lots of lovely sandwiches.

ORIGIN OF THE SANDWICH

In 1762, an English noble named John Montagu, the fourth earl of Sandwich, was on a gambling spree when he got hungry. He didn’t want to fold his hand, so he instructed a servant to place a piece of roast beef between two slices of bread. He could eat with one hand and play with the other. Thus the birth of what today is the most popular meal in the Western world.

So why don’t we do the “Sunday” roasts anymore? Why are the grills of America stocked with burgers and chicken parts only? Why do our ovens echo with emptiness? Remember the previously quoted Brillat-Savarin remark, “We can learn to be cooks, but we must be born knowing how to roast.” When he wrote this in the early years of the nineteenth century, roasting was still a medieval procedure involving iron spits and fiery pits (see

Grilling

). And in those days a cook who overcooked a “joint” of meat might be beaten with the charred appendage. (I had one thrown at me once, but that’s a story for another time.)

Despite the advent of the modern oven, roasting remains a mystery to most. This may be due to the fact that modern cookery is about recipes, and you just can’t learn roasting from a recipe any more than you can learn the tango from those cutout footprints they stick on the floor down at the Fred and Ginger Dance Academy.

For instance, a recipe can tell you to heat your oven to 350° F, to slather ingredients

x

,

y

, and

z

on a 4-pound beef eye-round roast, and to cook it for 1½ hours. But what if your roast is a 5-pounder? What if the recipe was formulated in a Bob’s oven and you own a Joe’s oven? What if you don’t have 1½ hours? What if all you can find is a pork loin roast? Are you out of luck? No, because B-Savarin was wrong. You can and should teach yourself to roast. It may take some time and attention, and you might even overcook a roast or two, but in the end you will be one of the few, the proud—the roasters.

By the way, the terms “roasting” and “baking” refer to the same method. The difference is the target food. If said food is a batter, or dough, or pastry, you’re baking. If it’s anything else, you’re roasting. The only dish I know of that steps out of line is ham. You always hear about “baked” ham, never “roasted” ham. And yet you’d never say “baked” turkey any more than you’d say “roasted” brownies. Strange, isn’t it?

THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO ROAST

Before the days of inexpensive, accurate, digital thermometers, roasters relied on voodooesque charts that calculated cooking times based on the temperature of the vessel and the gross weight of the target food. This equation has stranded many a cook over the years because weight doesn’t matter nearly as much as shape.

Master Profile: Roasting

Heat type:

dry

Mode of transmission

: 50:45:5 percent ratio of radiation to convection to conduction

Rate of transmission:

very slow

Common transmitters:

Air (convection), oven or container walls (radiation), container (conduction)

Temperature range:

from your lowest oven setting to your highest oven setting

Target food characteristics:

• relatively tender cuts of meat, including those from the loin and sirloin

• all poultry

• root vegetables and starch vegetables (potatoes)

• eggs

• a wide range of fruits, including tomatoes and apples

Non-culinary application:

curing pottery

AN ACCURATE OVEN TEMPERATURE

To tell the temperature of your oven, a coil-style oven thermometer works best. The principle behind these bimetallic strip thermometers is based on the fact that different metals expand at different rates as they are heated. In this case, a coil sensor, made of two different types of metal bonded together, is connected to a pointer on a dial face. The two metals expand at different rates, but because they are bonded together, work in unison to dictate the coil’s change in length as the temperature changes. This in turn causes the pointer on the dial to rotate to indicate the temperature. I like this style for the oven because they’re fairly accurate at oven temperatures and are easy to read even through dingy door glass.

SANDWICH-MAKING TIPS

•

A

good way to make a sandwich sturdy, besides toasting the bread is to use a layer of spreadable fat like butter or mayo to provide moisture, flavor, and a waterproof shield that prevents the bread from getting soggy.

•

A good way to cut a sandwich made on a long baguette is to wrap the finished sandwich in parchment paper, place clean rubber bands every 5 inches, then cut.

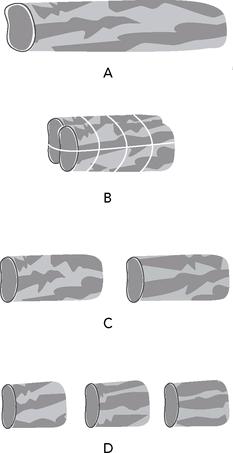

Case in point: pork tenderloin. If weight and oven temperature are the deciding factors, then

a

,

b

,

c,

and

d

should in fact be done at the same time, right?

Put these roasts in order from the first to be finished to the last.

The right answer is

c

-

a

-

b

, but what’s interesting is that

a

and

c

are very close to one another in total cooking time. What’s even more interesting is that even if you cooked only one piece of

c

,

a

still wouldn’t be far behind. That’s because the primary shape, not weight, is the deciding factor. Sure, one piece of

c

will cook quicker because its surface-to-mass ratio is a little higher than that of

a

, but the overall distance from the outside to the center is the same.

Despite an identical weight,

b

will take nearly twice as long to cook as

a

or

c

because its shape is different: its thickness has been doubled, so heat has to travel roughly twice as far into it.

Given that both pieces of

c

will cook a little faster than

a

, it stands to reason that cylindrical pieces of meat could be broken into several pieces to decrease cooking time. And since more surface area means more crust, you might consider breaking traditional roast shapes into single servings when appropriate (

d

). This might not work with a steamship round or even a prime rib, but various parts of the round, chuck, and loin do nicely (see

Beef Blueprint

).

The greater the surface-to-mass ratio, the quicker the cooking. In other words, something the shape of your arm is going to cook faster than something the shape of your head.

HOW MUCH HEAT?

Roasting is a bit like deep-frying in that it’s about even heating. The difference is that hot fat delivers heat via highly efficient conduction, while roasting depends on radiant heat and convection, both of which are relatively inefficient modes of heat transfer. This means that roasting is a relatively slow process, which is why it’s better suited to large, dense items that require longer to cook through than thinner cuts.

Tortoiselike though it may generally be, there’s still fast roasting and slow roasting. And which one you decide to use depends on the target food and your taste. Consider the cross section of your average hunk of beef—say, an eye of round roast—cooked in a 500° F oven (see

illustrations

). Like the growth rings of a tree, the roast shows us its thermal history. The outer crust, exposed for the longest time to the high heat has seared to a dark-brown and flavorful crust. As for the interior, we were hoping for medium-rare, and yet a great majority of the meat is well above that temperature; only the inner core is where we wanted it. We’re understandably disappointed. To heck with this roasting business, we say.

Roast Cutaways