IGMS Issue 44 (9 page)

Authors: IGMS

Cai's voice filled with hard emotions. "Men like him are always following me. Asking to do tests, offering to take samples, checking that I'm alright. They should just let it be, accept it. But they won't. They ask me about every thought my children share with me. Sometimes they put machines on my head and watch what is triggering in my brain. They don't care if I don't want to tell them. They just keep asking. And I'm not going downside, ever."

A chill went through Jake. Dictatorships on Earth had a way of monitoring people, but this was worse, an intrusion that neatly fit the label "Thought Police." He'd be damned if he'd let Major Blutnikov turn Malia into an object of study.

Doctor Venus said, "If the Major finds out that Malia has these abilities he'll never let her go."

"Men like the Major live for this kind of thing," Cai said. "Don't give in to their fears. Just accept that the Bruma are with Malia. They're a gift, not an illness."

A gift? That was pushing the crap cart too far.

But Andrea took his hand, and while they looked at each other, his thoughts tumbled into place.

Malia would always have the scars across her stomach. But if Cai was right, she would have something else as well. A link to another species. A connection that could stretch across the galaxy. A whole new kind of motherhood. He didn't need to ask Andrea to know she was thinking along the same lines.

"Why are you helping us?" Jake asked the Doctor.

"People in power have used diagnoses to have their way throughout history," he replied. "Illnesses like leprosy, HIV, and schizophrenia have caused people to be mistreated and isolated. Transsexuals and people with Down's Syndrome have been branded as sick deviants. I don't intend to spread those misconceptions to Blue Two."

Jake turned to Malia. "Is the tickling in your head disturbing you? Is it giving you a headache?"

She shook her head and smiled.

"No brain scan," Andrea said, echoing Jake's thoughts.

"There are no guarantees in life," Doctor Venus said. "But I think getting out of here as quickly as possible would be a very wise decision."

Cai nodded emphatically, and they said their goodbyes.

While the Durows waited for departure, Jake stood gazing one last time out the port window screen at the deepness of space outside. Empty still. But for the first time in ages he found himself staring at the stars that shone in the darkness, millions of stars offering what light they could.

It felt good to notice the light.

He turned to Andrea and saw the stars reflected in her eyes. He read anxiety as well, but the courage in her eyes clearly won out and settled over him.

"Let's go," he said. "It's time we moved on."

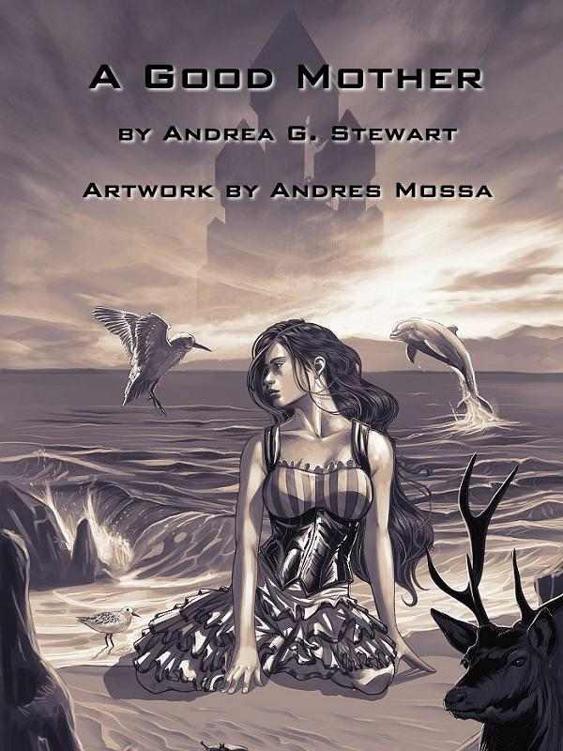

by Andrea G. Stewart

Artwork by Andres Mossa

Pehlu was a sandpiper the first time I met him.

In the pre-dawn hours, I escaped the confines of my fourth-level bed and crept to the shore. Even the sharp eyes and ears of third-grandmother didn't catch me. I went to the beach to be alone; only the fishermen were out on the pier, casting their lines into the sea.

I caught Pehlu the sandpiper with a laugh in the back of my throat, my outstretched fingers a net. The ocean's breeze ruffled the feathers over my knuckles and his round eyes stared at me, bright as polished stones. He fit neatly in my thirteen-year-old hands, and his heartbeat thrummed against my palms.

When I brought the bird level with my eyes, he spoke.

"Ulaa."

I nearly dropped him. "How do you know my name?"

"Each time you come to the shore, you chase the birds and cry out, 'Ulaa comes for you!'"

A flush crept up my neck. "I do not."

"You do. I've seen it."

"There are many girls my age living on the island. It could have been someone who only looked like me."

The bird did not reply. His legs kicked the empty air beneath my hands.

"Well," I said, finally, "what is

your

name?"

"Peluvisinaka."

"I like Pehlu better."

"Very well. Can you please put me down?"

I could not think of how to deny so polite a request, so I placed him back on the sand.

He shook himself and began to preen.

"You're not a real sandpiper," I said. I crouched, and the salt-seaweed smell of the ocean washed over me. A tiny crab, disturbed by my presence, scuttled back into its hole.

"I am, for now."

"You're a

kailun

-- a spirit."

He snatched up a beetle and swallowed it. "Whatever gave you that idea?"

"You talk. Sandpipers don't talk."

Pehlu looked up at me, his head tilted to the side. "Mother tells me I shouldn't."

A sudden rush of kinship filled my chest. "My mother tells me I shouldn't run off to the shore in the mornings. But my cousins above and below me snore, and it gets hot in the sleeper, and sometimes I feel that if I don't get away, my own skin will suffocate me."

The sandpiper nodded, wisely as any grandfather. "I feel that way too, before I grow."

I thought for a moment. "When you grow big enough, one of my people's grandparents will eat you. That's what happens to all the

kailun

."

"Maybe you can keep me safe."

I straightened, rocking my knees onto the cold sand. "We should be friends. I don't have any."

"Neither do I."

"Ulaa!" My mother's voice echoed down the beach. I glanced back and saw her striding toward me, her long brown hair whipping in the wind. The sun had crested the horizon, and others were making their way to the shore. By the time it was afternoon, a swell and press of bodies would move from the sleepers to the outdoors. The waves would be dotted with children, the sand covered with people plying their trades.

"I have to go," I whispered before rising to my feet and letting my mother overtake me.

I did not protest as she took my hand, as she scolded me, as she led me back through the city and into the hot, musty air of the sleeper. She told me to go back to bed, so I did -- climbing the ladder to my fourth-level cot. Around me, a hundred throats breathed in the darkness: mothers and fathers, children, third and fourth and tenth-grandparents. When the wind blew, the bamboo struts creaked and the lattice-walls swayed.

"Pehlu," I whispered as I lay there, listening. I hooked my thumbs around one another and fluttered my fingers like a bird.

Nineteenth-grandfather ate a

kailun

the very next day. All of his family gathered in the city square to watch the ritual. I couldn't count how many of us there were -- I stood near the front with my mother, aunts and uncles, and cousins. Around us, the buildings loomed like giant, crooked fingers. The mountains beyond the city were cut into farming terraces.

My mother leaned over to whisper in my ear. "Nineteenth-grandfather is my father's father," she said. "What will that make you, when your children have children?"

It took me a moment to puzzle out the words. "Twenty-second-grandmother."

She patted my shoulder in silent praise.

Beside me, my cousins poked and jostled one another. "Only a good mother gives her children a name," one boy said to the other. He squared his shoulders, imaginary bow held in his hands. I knew the words he spoke -- all children did. "What do I see before me but a herd of wild animals, all of them brought up by bad mothers?"

The other, younger boy pranced from side to side, imitating a

kailun

in the form of a deer. "Ooh, me, me! I have a name! I have a good mother!"

And the first boy nocked a pretend arrow before letting it fly.

The dramatic "death" of my youngest cousin was enough to throw off the balance of several people behind us. One of my uncles seized both boys by their ears. "That's enough. Quiet, both of you."

They settled down just as first-grandmother emerged from her house with a

kailun

flask. I only ever saw first-grandmother during the rituals. Though her hair was white, her face was unlined, her hands thin and smooth. She wore a long, blue robe that swept the ground behind her. No expression marred her face.

Through the gaps in her fingers, I could see the bright glow of the

kailun

. The light flickered as the spirit moved. She brought the flask to the chair where nineteenth-grandfather sat. He hunched in his seat, his gnarled fingers curling around the armrests like tree roots.

After she uncorked the flask and tipped it over his mouth, her hands came away. A tiny blue light, so bright it hurt to look at, pressed against the glass. Nineteenth-grandfather's chest expanded as he sucked at the air in the flask.

The

kailun

disappeared past his teeth.

As we watched, nineteenth-grandfather, whom I'd always known as an old man, became young again.

"Pehlu!" I called out. "Pehlu!" My feet sank into the sand as I ran toward the waves. I spun in a circle, searching. The sandpipers scattered at the sound of my voice; none responded. My breath formed a mist in the early morning air.

"Pehlu, Ulaa comes for you!"

A lone sandpiper emerged from the sea grass. "I'm here, Ulaa, no need to shout."

I dropped to the ground, heedless of the sand upon my nightgown. "I'm so glad you came."

"Me too. I mean, glad that

you

came. I didn't think you would. Your mother seemed very angry."

I shrugged, though my stomach flipped at the thought of her scolding. "I do what she says, except for this. What is it like, being a sandpiper?"

He folded his legs beneath him and told me. And told me more than that. Before he was a sandpiper, he was a sparrow. Before a sparrow, he was a clam. The first thing he remembered being was a spider.

I told him of my grandparents, of my cousins, of my aunts and uncles.

"There are so many people," he said.

"Yes, there are."

We lapsed into a comfortable silence, listening to the waves upon the shore and the wind through the rushes, until my mother came for me.