If These Walls Had Ears (14 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

Not all was perfect, however. Ruth saw problems and felt an uneasiness that couldn’t be solved by the simple positioning of

cherished possessions. She had some painting done before they moved in, and she noticed that the downstairs bathroom tile

was loose. When the tile man began poking around, he found that all the joists beneath that floor had rotted. Water had been

seeping in from somewhere. Ruth and Billie had to put in a whole new subfloor, but that wasn’t the worst of it. From then

on, Billie would worry about water and whether more of it was coming in—and, if so, from where. A house is man’s attempt to

stave off the anarchy of nature. Ripping up that floor had allowed a disturbing glimpse into the house’s secret life. It’s

more comfortable not to know about such things.

Ruth remodeled the whole bathroom in pink-and-black tile, a color combination then still considered avant-garde but one that

all the trendy magazines would be touting before long. She also replaced the single pedestal sink with two chrome-legged lavatories.

As for the rest of the problems, they would have to wait. The kitchen still had one of those old four-legged ceramic sinks

with the built-in drain board; Ruth surely wanted to replace that. Also, the house was a freezer. There was no heating system,

just a few small stoves here and there. In the living room fireplace, a gas heater had been stuck into the space where the

logs used to go. At some point, Jessie Armour had plugged up the fireplace and inserted the heater to try to ward off the

cold. The Murphrees knew nothing of Jessie Armour’s life, of course. All they saw was an old heater that should’ve been vented

but wasn’t, and that didn’t put out much heat anyway. Fortunately, warmer weather was coming. Ruth made a note to have floor

furnaces installed as soon as possible.

Beyond that, Ruth had problems with Jessie’s French doors. All that glass between the dining room and the bedroom bothered

her, made the bedroom feel too public for Ruth’s taste. Besides, French doors were too formal for the postwar style. The modern

house was loose, open, more free-form. If you sat in the living room of this Craftsman bungalow, browsing through

The Saturday Evening Post

and

McCall’s,

when you looked up at your own surroundings, this house suddenly felt old and tight. The flow that Charlie Armour had worked

so hard to achieve with French doors seemed, to the Murphrees, to make the house feel “all chopped up.” That indictment extended

to the doors separating the living and dining rooms, and even to the narrow breakfast room with its clever built-in serving

counter that Jessie had loved.

New times require new thinking. So do new owners.

One year after they moved into this house, Ruth and Billie took part in a ritual that was symbolic of the new postwar optimism:

They conceived another child. The baby, their third daughter, was born three days after Christmas. They named her Joyce. She

was the very first child born to this house.

As if in celebration of the postwar ideal of family, Billie surprised his girls with a special gift that Christmas of 1948.

It was one of the new 16-mm Kodak movie cameras that were all the rage. Using it was quite a production, but Billie didn’t

care—not, at least, on birthdays and holidays, when the clan was over and the table was set and everyone was all smiles. And

on nights when he would show the home movies, they would gather in the living room, Martha and Pat fighting for the best spot

on the floor. As their grainy figures tottered across the screen, the Murphrees would laugh and clap, basking in the flickering

image of family that danced from the projector on a smoky beam of light.

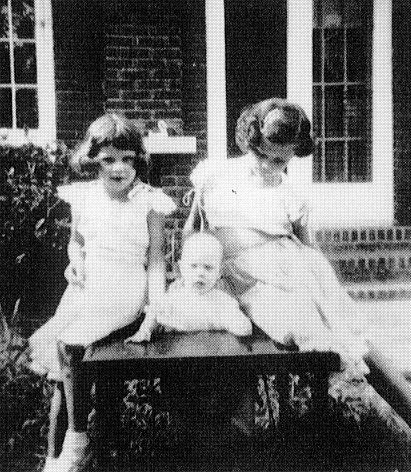

The Murphree girls—pat,Joyce,and Martha—in the side yard in 1949.

Murphree

1949

1956

I

’m riveted by a photograph of the three Murphree daughters taken in the early summer of 1949, posed in the side yard in approximately

the same spot where Jessie, Jane, and Charles Armour and Grandma Jackson were pictured with Uncle Ben on that long-ago Christmas

after Charlie’s mother had descended upon the house. The photo of the Murphree girls is every bit as revealing about its era

as that other frozen moment of time was about its own.

Pat, just-turned six, and Martha, almost nine, are sitting on opposite edges of the table surrounding Joyce’s built-in baby

seat. Pat, her hair in little-girl bangs, is wearing a lace-shouldered little-girl sundress and white socks and Mary Janes,

with a little-girl skinned shin and a little-girl absence of front teeth in her open mouth. She’s facing the camera straight

on, imploring it to—what?—not overlook her? Meanwhile, Martha all but languishes on the table, her eyes coyly downturned,

her hair pulled to the side. All that’s missing is a flower over her ear. She wears a ruffled bare-midriff top and skirt and

shows an astonishingly long, bare leg, tapering to a sockless foot in an open sandal. Wide-eyed, six-and-a-half-month-old

Joyce, oblivious to the drama going on around her, studies the camera notas something to be responded to emotionally—something

to be needed or seduced—but as merely a fascinating gadget with moving parts she’d like to get her hands on.

I find this photo compelling because the Murphree household was one dominated by females—much like the one I now live in—and

the rivalries are palpable. The great unseen presence, of course, is Ruth, with whom all of the girls in this picture—even

baby Joyce, later—were in some degree of competition. As was Billie, I guess, husbands and wives being the way they are.

Despite her precocious glamour in this snapshot, Martha was the tomboy, the adventurous one—the one Ruth found irrepressible.

She and two other girls in the neighborhood had a group they proudly called the Lee Street Terrors. When a new house was built

at Woodlawn and Holly, Martha and her friends were so incensed over the homeowner’s taking

their

vacant lot that they poured a concoction of black ink, Kool-Aid, and mud through the mail slot, and it landed on the people’s

new carpet. Another time, just after Ruth had bought some fashionable new pull-cord draperies, she came home and found that

Martha and her friend across Lee had rigged up a tin-can phone using the drapery cord.

Martha was almost six and Pat nearly four when they moved to Holly Street, and, even then, the two spent much of their time

at each other’s throats. Martha thought Pat was a crybaby. “She whined and complained about everything,” Martha says, “and

she was prissy. I just didn’t have much patience with that type of individual.” Martha loved dogs; Pat loved cats. Not only

that, but every year each daughter got to choose the meal that would be served on her birthday. Pat always asked for liver

and onions.

Their shared bedroom was a war zone. “We played the games all sisters play,” Pat remembers: “You’re on my side of the bed.

Here’s the line—don’t get your foot on my side!’” When Joyce came along, Ruth and Billie separated the older girls. Martha,

being the older andmore aggressive, claimed the big room with the cedar closet. Pat and her dolls shared the smaller bedroom

across the hall.

In the fall of 1992, Martha arid Joyce returned to 501 Holly Street. Joyce had been in the house once a few years before,

when it was for sale, but for Martha this was the first visit in twenty-six years. The sisters were now mothers and wives,

but as they walked through the rooms of their childhood home, I watched them become girls again.They reminded me of Jung’s

story of probing deeper into himself the further he ventured into the house of his dream. At first, they spoke of halcyon

days with no worries; then as they talked, their memories grew darker and more complex.

Martha remembered straddling the floor furnaces Billie and Ruth installed in the music room arid the hall. Joyce remembered

riding her tricycle down the stairs, knocking out her front teeth on the oak dining table. Martha remembered living in a secret

world in which her bedroom floor represented vague arid unnamed dangers, and the only way to avoid them was never to touch

the floor. She mastered the art of walking the entire circuniference of the room on doorknobs, swinging over to dressers,

and so on all the way around. Joyce remembered the day the hot-water tank caught fire and destroyed part of the kitchen (giving

Ruth an opportunity to redecorate). She recalled the neighborhood as a wonderful place to roam—with the exception of the creepy

old Retail house on the next corner, which she was scared to walk by because everybody said it was haunted.

Then Joyce asked, “Is my dog’s name still in the sidewalk by the house?” I told her I had never seen it. She took me outside.

In the spot where the fieldstone walk curves away from the house toward Lee, she pulled back the grass that had grown over

the edge of the walk. There it was—AUSTA, along with Joyce’s initials. How many other secrets, I wondered, have time and this

house tried to conceal?

* * *

For the Murphree girls, life at 501 Holly breaks into two parts—before the mid-1950s, and after. Before was magical; after

was torment.

I imagine the early Murphrees as very much like one of those sitcom families on TV. Billie was among the first in town to

buy his family a television set. It was a big dark mahogany console model, with an octagonal screen and rabbit ears on top.

They put it in the living room, but then Ruth decided the children would ruin the good furniture. That gave her a good excuse

to do something about those French doors to the bedroom: She had them ripped out and replaced by a solid wall, with a floor-to-ceiling

bookcase on the bedroom side.

Except that this was no longer the bedroom—it was now the den. It was a quiet and cozy spot for Ruth to thumb through her

Saturday Evening Post

and for Billie to concentrate on his Saturday-evening Bible study for Sunday morning’s lesson. Ruth had her bedroom furniture

moved to the back room, where Martha and Pat had slept before Ruth separated them. In the den, Ruth arranged a couple of easy

chairs and a long sofa. The TV set was also brought in, positioned near the door to the music room. Billie didn’t allow much

TV watching on school nights, but on Fridays the family gathered to watch

The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.

The nearest TV station being Memphis, Martha and Pat had to squint through clouds of snow to catch a glimpse of their heartthrob,

Ricky Nelson.

As long as she was adding the bedroom wall, Ruth went ahead and removed the one between the kitchen and the breakfast room.

That gave her live-in maid, Mattie (who resided in the garage’s “servant’s quarters,” one room with a chain-pull toilet tucked

into a tiny space beneath wooden outside steps), more space to prepare sumptuous desserts for Ruth’s afternoon bridge parties.

Those parties had become more frequent in 1950, when Ruth quit her job with Brooks Hays to become a full-time bridge-playing,house-remodeling

mother and housewife. She wore hats and went shopping downtown. She lunched. She sent her sheets out to be pressed. Life was

good. There was a picnic table in the side yard, and on those pre-air conditioning summer evenings, Ruth and Billie would

frequently invite their friends or family over for cookouts. Later, the webbed lawn chairs would be arranged in a circle in

the dark, and the talk would be as soft as the air itself, a comfortable murmur of prosperity punctuated occasionally by sparkling

laughter.

Ruth and Billie’s competition was relatively low-key in those days. The girls say Ruth resented Billie’s interminable hand

shaking and socializing after church, but, then, Billie was a deacon and superintendent of the Sunday school. Sometimes, especially

later, the girls saw Ruth try to pick fights with Billie, but he would never engage her. Ruth called Billie by his given name,

but he called her “Mama.” At times when he needed a little extra leverage—such as when he got Martha the goat—he would call

her “Mommy.” For all his Baptist piety, Billie Murphree was a bit of a flirt with women. “Now, Mommy,” he would say, “you’re

not going to be mad at your old daddy, are you?” Everybody said Billie had the patience of Job. He never got angry at Ruth—or,

if he did, he didn’t show it.