If These Walls Had Ears (5 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

Another big attraction to the Armours was an amusement park that some old-timers still called Forest Park but that had recently

been refurbished and renamed White City. The ostensible reason for the name change was that all the structures had been painted

a sparkling white, but the not-so-subtle message to Little Rock Negroes was no doubt considered a happy by-product. The park—which,

the Armours learned, had originally been built to attract a streetcar line to the Heights—now featured an outdoor swimming

pool that was a whole city block long and half a block wide. Parkgoers could even enjoy the recent invention called the “dodgem”—four

padded cars with erratic steering and guaranteed collisions. The automobile culture had changed the park in other ways, too—White

City now included a campground for tourists traveling by car.

Charlie and Jessie liked what they saw. When they drove along Woodlawn Street, they found it a kind of church row. There were

a Methodist, an Episcopal, and a Presbyterian church all within three blocks of one another. On down Woodlawn, there was even

a Baptist church just where Woodlawn ran into Prospect. In Hillcrest, no matter what denomination you were, you could get

up on a Sunday morning and

walk

to church if you wanted.

It was time. Jessie knew it, and Charlie knew she knew it. It was time to dig in and make a stand, if ever they were going

to do it. The stars hadn’t been so auspiciously aligned at any time during their eleven years of marriage. Building a house,

which they would have to do, was a major commitment—especially for Charlie. It’s a frightening thing, especially for a man,

to say, This is it. This is where I live and where I’m going to live—no matter what. You cross off all your options. You have

to make it work

here.

At least Charlie could be comforted by the fact that nice houses in Hillcrest didn’t sit empty—if, God forbid, something

happened and they were forced to move again.

They began searching for exactly the right lot—one close to schools, churches, and the shopping district. Finally, they found

a large parcel of land on the corner of Lee and Holly. It was on a hill, which was nice—the better to catch the breezes. The

property was owned by a Melissa Retan, who, the Armours were told, had once owned the big Queen Anne house right behind this

lot—so close, in fact, that shade from the imposing Retan carriage house fell on this property in the mornings. Melissa and

her late husband, Albert, had been part of the original group who had developed the Heights. The house next to the Retan house

was the Auten place, home of another Heights founder, who had died only recently, in 1918. Albert Retan had died way back

in 1909, and Melissa had decided the big house was too much for her and her remaining single daughter, Zillah. So she had

sold the property and moved to a smaller place.

Charlie and Jessie were impressed with the neighborhood. Holly Street was only one block long, and it was a very nice block.

Across the street from the lot they were considering was a smallish but very neat bungalow with an interesting Oriental trellis

on the gable. A substantial house stood next door to the north—a wooden two-story with a porch and decorative woodwork on

the windows. Catty-cornered across the street was a big, comfortable-looking house with a porch and columns out in front.

And next door to that, on the corner of Woodlawn and Holly, there was a

fabulous

house—huge, with upper and lower wraparound verandas and exotic mimosa trees in the yard. Combine that with the Retan and

Auten houses just to the rear—you could even say the Retan house was

next door—

and

,

yes, this was a neighborhood anyone would be proud to drive home to every day.

On July 18, 1923, Charlie and Jessie paid Melissa Retan two thousand dollars for the land, which was officially known as “Pulaski

Heights block 004, lot 007, the west one hundred feet of 007, and the south 40 feet of the west 100 feet of 008.” A month

later, they took out a loan of $5,800 to build the house. In the 1920s, the average annual income in the United States was

one thousand dollars. What Charlie was to be making at Arkola, I have no idea. But while there were certainly many houses

more expensive in Hillcrest, this was nevertheless a major expense.

They also had the added fee of their architect, a man named H. Ray Burks. The generally acknowledged “best” architect working

in Hillcrest in 1923 was Charles Thompson, who designed very large and very showy homes. He had been working in Little Rock

for many years, and in fact was said to have designed the Queen Anne house for the Retans in 1893. Another well-known Heights

architect was K. E. N. Cole, who specialized in bungalows. Ray Burks would go on to create numerous houses and buildings in

Hillcrest, but in 1923, at age thirty-three, he still had his best work ahead of him. He was a member of Kiwanis, as was Charlie

Armour. I like to think of their meeting over rubber chicken and too-green English peas, two loyal clubmen happy to do business

within the fold.

But what

kind

of business? In 1923, the trends in house design included a fair amount of harkening back to the romantic styles of the past,

architecture that whispered—or sometimes shouted—its alignment with English, Spanish, or French designs. When Charlie and

Jessie drove through the Heights, they saw quite a few houses that were English Revival, Colonial Revival, or American Foursquare.

The style they saw the most, however, was the Craftsman bungalow, or some variation on it. During the period of Hillcrest’s

first major development—between 1910 and 1920—the Craftsman influence, an architectural offshoot of the English Arts and Crafts

movement of the late 1800s, was at its peak in the United States. Arts and Crafts celebrated individual craftsmanship as opposed

to tasteless overmechanization.

I think I can understand why Charlie and Jessie were the Craftsman type. Jessie liked her nice clothes and her clubs, but

essentially she was a practical woman. She was a Minnesotan, and I’ve lived in Minnesota. Minnesotans are unemotional, at

least compared with the Southern women Jessie now lived her life around. She was sure of herself and her abilities. In a sense,

she applied the Arts and Crafts ideals to the running of her home: She took joy in cooking, in making the children’s clothes,

in being a hands-on mother and wife. Charlie may’ve been less practical than his wife, but he wasn’t a pretentious man. Besides,

the Craftsman bungalow was the most house you could build for the money, and it was infinitely adaptable.

He and Jessie opted for a house larger than the smallest bungalow, but smaller than a high-style Craftsman. It wouldn’t be

as big as most of the other houses in the neighborhood, but it wouldn’t be the smallest, either. Also, the extra property

would carry some weight. When you approached from the west on Lee Street, you would see the house there on the high ground.

The overall effect would be impressive. And the house would be very nice—one story with a big porch, plus a garage and servant’s

quarters. A good, sturdy middle-class house.

Charlie spent much time with Ray Burks trying to figure out the most advantageous layout for breezes and air flow. He wanted

a house that

breathed.

The house would face west, and the porch would stretch two-thirds of the way across the front and wrap slightly on the south

side—that way, it could catch the wind from all four directions. Wide eaves would keep out the rain and the hot southern and

western sun. Casement windows, a traditional Craftsman touch, would allow the Armours to open the house, and interior French

doors throughout much of the downstairs would let the air circulate from one side to the other. Those French doors also had

another purpose. As Charlie and the architect were planning, Jessie said to her husband, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could

dance

here!” It would indeed, “ Charlie said. The French doors, which opened the house to a world of such possibilities, were immediately

sketched in.

While their house was being built, the family rented a place nine blocks east, on a street called Midland. Every day before

school started that fall, young Charles and Jane would trudge up Lee Street—Charles half a block ahead so as not to be seen

walking with his seven-year-old sister—past the Pulaski Heights Elementary they would attend, toward the construction site.

Charles monitored everything that happened. For a while, he even got himself hired on as a kind of water boy and nail fetcher,

necessary credentials for mingling in that world of men. As for Jane, she stood by on the Holly Street side and watched the

workers framing in the room that she had already moved into in her mind.

For the Armours, who had wandered so long, this house must’ve felt like a new beginning—the first step toward finally making

a

home.

Jessie was beside herself. That Christmas, when they were finally in, she sent photographs of the house to friends and relatives.”

The new house on Holly, “ she wrote on the back,”—complete at last!”

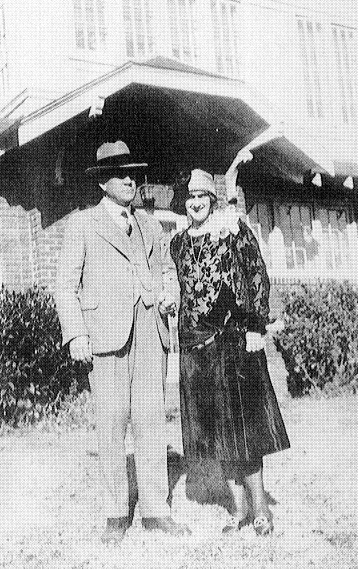

Charlie and Jessie Armour in the side yard. This was in the late twenties, when all things still seemed possible.

Armour

1923

1926

1926A

ll houses are fantasy, constructed as much of desires and dreams as wood and brick. They’re receptacles to hold not just us

but also everything we want to be. Sometimes we don’t even know what that is. Sometimes we move into houses empty and expect

them to fill

us

up.

Houses have such power because they live in us as much as we live in them. I know a woman, a psychologist, who tells me that

Carl Jung’s theory of a collective unconscious came to him after he had dreamed about a house. He described the dream this

way:

I was in a house I didn’t know. It was my house. In the upper house there was a kind of salon furnished in Rococo style. I

did not know what the lower floor looked like. There everything was much older. This part of the house must date from the

fifteenth or sixteenth century. The floors are of a red brick, the furnishings are medieval. I went from one room to another

thinking, “Now 1 really must explore the whole house.” I came upon a heavy door and opened it. A stone stairway led me to

a cellar. Descending again, I found myself in a beautiful vaulted room which looked exceedingly ancient. The walls datedfrom

Roman times. The floor was of stone slabs, and in one of these I discovered a ring. The slab lifted. I saw a staircase of

narrow stone steps leading down. I descended and entered a low cave. In dust were scattered bones and broken pottery, like

remains of a primitive culture. I discovered two human skulls, obviously very old and half disintegrated.

Then I awoke. It was plain to me that the house represented an image of the psyche.

No

wonder

we have such strong feelings toward our houses: They are us; we are them. Dream analysts will tell you that when you dream

about a house, many times you’re actually dreaming about yourself. Jung used his house dream to develop a theory about certain

universal symbols—the house among them—and the reason people all over the world respond so emotionally to them. He believed

that dreams are the way our unconscious self communicates with our conscious self. What excited him about the house dream

was that he had spoken to himself from a deeper level, and with a structure that illustrated what was happening. To Jung,

the salon represented consciousness, and the ground floor stood for the first, or personal, level of the unconscious. Many

dreams come from there. As he went deeper, though, the scene became darker and more alien. He interpreted the Roman cellar

and the prehistoric cave as signifying past times and past stages of consciousness—times and consciousness beyond the personal

self. From this dream, he began research that resulted in his notion of

archetypes,

primordial images shaped by the repeated experience of our ancestors and expressed in myths, dreams, religion, literature.

These images are prelogical. They’re imprinted on the deepest levels of our being. So when you see a house with a cozy front

porch, all sorts of feelings and urges many of them entirely irrational—may wash over you. It’s happened to many people right

here at 501 Holly.