If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (46 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

42

DOING THE TV SHUFFLE

When you've starred in a TV show, even one that's low rated, an odd chain of events are set in motion. After

Brisco

was canceled, I found myself able to travel freely within the realm of television because the credibility checks, once routine, became almost nonexistent. Suddenly, roles were simply "offered."

The first show to welcome me like this was

Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman.

A certain logic prevailed here -- this show was also produced by Warner Bros., and a writer/producer from

Brisco

had since defected to this camp. It was a good match of sensibilities, and I managed to slink in and out of three episodes as suave bad guy, Bill Church, Jr.

On the show, Peter Boyle played my evil father. As a character actor in a number of memorable films such as

Taxi Driver

and

Young Frankenstein,

he was no hack but, like so many other actors in his position, Peter was lured to television.

The medium can do odd things to actors -- like beat them into submission. Not every actor can spit out lines at the drop of a hat and nail it in one take. Film actors, in particular, don't always enjoy a smooth transition.

Peter did a take that would never have been printed on any film set, low budget or not -- he stumbled, fumbled, and groped his way through it. I was sure they would have another go at it, but the director glanced at his watch.

"Great, Peter," he announced. "Okay, moving on..."

Peter looked at me with an incredulous expression.

"It just doesn't matter, does it?"

Still, it was fun to work on the familiar Warner back lot, this time dressed in modern garb. As I stood behind the façade of a doorway, waiting for my cue, I glanced at the unpainted plywood. There, written in a black marker, was a note I had scribbled late one night while shooting

Brisco. Brisco was here -- 2/22/94,

it stated simply.

Sam Raimi got a decidedly twisted TV show of his own up and running called

American Gothic.

My agent spotted a good guest-starring role, but Sam was hesitant to cast me because the show was "serious." Eventually, it led to a very strange phone call with the Grand Poobah himself.

Sam: Listen, mister, if I give you this role, you have to be serious.

Bruce: What did you think I was going to do, wink at the camera the whole time?

Sam: Well, this isn't like

Brisco,

you know...

Bruce: Sam,

Brisco

was its own beast. For Christ's sake, I'm an

actor.

I think I can reach deep into the bowels of my soul and somehow manage to keep a straight face. Besides that, what other actor is gonna lie in a coffin and let you pour a box of live cockroaches on their face?

Sam: Hmmm, good point...

The "serious" vs. "funny" issue rattled me.

My God,

I reasoned with myself,

I'm not a buffoon. As an actor, I should be able to do anything they throw at me... right?

As a result, I vowed to jump at anything dramatic that came my way. One such project was

Homicide: Life on the Streets.

The first phone call with producer Tom Fontana came as a complete surprise.

"So, is there anything you'd like to do?" he asked, casually.

"What do you mean? Like, what role would I like to play?"

"Yeah."

"Uh, gee... can I think about that for a couple days and get back to you?"

"Sure, just give me a call."

I was really turned around by this -- actors are usually in the position of begging producers to let them play a certain role. Here was an offer I most certainly could not refuse. In fact, I did have a notion about loopholes in our justice system and pitched Tom a very loose idea several days later. His response further confounded me.

"Yeah, cool. We'll do a two-parter," he said as if it happened every day.

Within a month, I found myself in Baltimore shooting a strikingly similar story. The writers created a fine character -- a police officer faced with the moral dilemma of whether or not to take justice into his own hands. Creatively, the experience was as close to perfection as I could have hoped for.

Other TV gigs materialized out of thin air. I got a call one morning to see if I could drop by the Disney lot and meet with Ellen DeGeneres and her producers about a role during their lunch break.

The meeting was only a few minutes long, and after a quick, closed-door huddle, I was invited to read a few scenes with Ellen and the director, Gil. The thrust of this session was really to make sure I could handle the snappy pace of sitcoms, something I had not yet done.

I guess now it was an issue of whether I could be funny

enough.

After another closed-door meeting, the casting agent approached me with an almost apologetic look on her face.

"Bruce, um... what are you doing for the rest of the day?"

"Nothing in particular, why?"

"Well, we need you to go into rehearsals, right

now..."

I walked over to the stage, hastily introduced myself to the other cast members, and got to work. This was a Wednesday afternoon -- the show was taped two days later, and voila, I was a sitcom actor. The undefined commitment on

Ellen

eventually blossomed into eight episodes, and it was a pleasure to learn a new side to my craft.

Sitcoms are a freaky atmosphere -- the entire week of rehearsal is spent trying to maximize the humor in every scene. To do this, the writing staff engaged in the most extensive script changes I had ever witnessed. The script from Monday's read-through would almost invariably be completely rewritten overnight, and Tuesday's rewrite wound up on my doorstep Wednesday morning.

When do these poor bastards sleep?

I'd ask myself.

By Thursday, the script was usually beaten into shape and the technical stuff would take control. Friday night, a studio audience was recruited, as well as a comedian to keep them "up" during scene changes.

It was a lot of fun to watch Ellen, by this time an expert at the medium, work her way through a show. If the first take went well, she'd riff on the second take, tossing in a few curves, to the delight of both the cast and the viewing audience.

I was glad to be a part of the last "Out" episode. My character, Ed Billik, a right-wing kind of guy, was the dissenting voice in Ellen's journey to an openly gay network character. Much to her credit, this was Ellen's idea, and it made for some good drama in the middle of an otherwise funny show.

Another abstract notion sprang from my new TV status: the development deal. This is a relationship formed between an actor (or writer, etc.) and a production company and/or TV network whereby they pay you not to work for anyone else while a mutually agreeable concept for a new show is developed. Following

Brisco

, I engaged in several such deals.

Meetings were first on the agenda -- dozens of meetings. Notions were kicked around with executives to make sure we were all on the same page, and we'd try like hell to define the type of show, its format and a rough time slot. Once this was hashed out, I spent the next several months meeting with what seemed to be every TV writer in Southern California to hear their pitches:

Joe Writer: It's kind of like

The Rockford Files

meets

Land of the Giants...

Bruce: Gee, an incomprehensible blend of two shows from twenty years ago... that ought to knock 'em dead...

Jeff Writer: See, you're an ambulance-chasing lawyer, and it's all about your private life...

Bruce: Let me get this straight -- we're supposed to

like

this guy?

Jane Writer: Get this: You're a gym teacher by day and an international spy by night...

Bruce: Excuse me, I think I'm double parked...

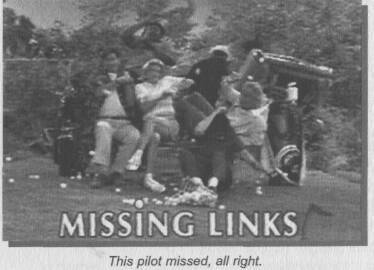

Eventually, the ideas all blended into a mishmash of baloney. More times than not, a show never gets on the air, but sometimes you get close. A development deal with ABC led to a sitcom pilot called

Missing Links.

The concept was based on a successful book and it operated in a milieu that I enjoyed. If I were pitching it to myself, I'd explain it as

Cheers

at a low-rent, public golf course.

The pilot went over well with our "live" audience and was one of the highest-rated sitcoms in their testing process that year, but ABC "didn't have a slot for it." This was a heartbreaker, and I'd be a liar if I said this experience didn't take a bit of the wind out of my sails.

Christ, am I just killing myself for no reason?

People often wonder why some actors fall off the face of the earth for no apparent reason. I've got news for you -- there is

always

a reason, and frustration with the business is a huge factor.

43

"X" MARKS THE SPOT:

THE GREAT WHEEL TURNS

When most people think of

The X-Files,

they think of paranoia, mystery, and science fiction. I think of farts.

David Duchovny, known for his sober performances on screen, was actually a funny guy. One night on set, he got his hands on a fart cup -- you know, those plastic cups, filled with a gooey substance, and he couldn't put it down. Eventually, we got into something of a farting contest, to see who could simulate the best potato chip fart (fast and dry), or the raunchiest Taco fart (slow and wet). We called it a draw when the crew couldn't handle it anymore.

Appearing on

The X-Files

was an interesting experience for several reasons -- it marked not only a return to the Fox network, but a chance to join up with the show that

Brisco

preceded, seemingly a hundred years ago.