If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (25 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

To break up the grind, Sam and I would routinely sneak away at lunch time to a video arcade called Fascination, and dull our senses even more by playing rounds of Asteroids and Berserk. Sam, with his innate ability to blow the living crap out of anything and anyone, excelled at both.

One day at the arcade, we were both surprised to see director Brian DePalma, doing the same thing. Apparently, he had been at the same sound facility, finishing up his film,

Blow Out,

with John Travolta.

Sam brazenly approached Mr. DePalma and half asked, half challenged him to a round of

Berserk.

DePalma, not exactly Mr. Amiable, agreed, and I'm pleased to say that Sam kicked h is A-picture butt from one end of Broadway to the other.

HOW LOW CAN YOU GO?

Pretty low.

With a finished 16mm film we could tour college campuses for years, we could screen our film on every aircraft carrier in the Pacific -- but could we get it into theaters? No. To do this, we had to get the film enlarged ("blown up") to the industry standard of 35mm.

Our investments were all sold off -- National Bank of Detroit turned its nose up at the prospects of any more business and every relative we knew had been tapped out. A phrase we began to hear a lot was, "Guys, no more means

no more."

Who could we swindle next? The answer was very close to home. I spotted my recently divorced Dad whispering to himself in a lawn chair behind our house one summer evening. Mentally, he was on another planet. Prodigal son that I was, I went for the jugular.

"Hey, Pop..."

"...Huh?"

"Uh, now that you and Mom are... well, you know... do you have any plans for that property up north?"

"Not really, why?"

"Well, I figured since you might not be going up there as much, me and the boys could get some use out of it."

"Go on up whenever you want," Charlie said.

"Oh, uh thanks, Dad, but what I meant was... (wince)... if you'd be willing to let me put the property up as collateral, we could get a loan to finish the flick..."

As the words came out, I astonished even myself. I was sure the answer would be returned to me in the form of loud invectives, but Charlie, God bless him, without so much as a glance, tossed a hand in the air.

"Whatever..."

Conning Dad was the easy part -- the real trick was getting the loan officer of the Mid-Michigan bank in Gladwin, Michigan, to understand the concept of a blowup.

The officer, tired of our confusing, technical explanation, finally stopped us with, "Look, fellas, I don't really give a rat's ass what a

blowup

is. It's pretty simple -- you return the money when the loan is due, or you risk losing the property. In the meantime, blow up whatever you'd like..."

21

THE FIRST PICTURE SHOW

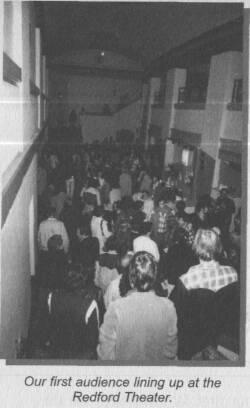

Because of the time and effort it took to get our first film finished, we decided to throw a big premiere and pull out all the stops -- this turned out to be a mini-production of its own.

Most importantly, we needed the proper venue. The Redford Theater, a grand old revival house, circa 1929, was ideal -- it could seat over 1,000 patrons easily, had a gigantic screen and boasted a fully restored pipe organ that rose from the orchestra pit. As the lights of the theater dimmed, "stars" twinkled subtly in the painted "sky."

Many of my Saturday evenings had been spent there watching newly minted prints of

Ben Hur, Sound of Music

and

Bridge on the River Kwai.

It was a splendid place to launch our film.

We began to put together a show within a show -- custom tickets, programs, and a creepy wind track to create the right tone in the auditorium. For giggles, we posted an ambulance and a security guard in front of the theater -- in case any patron found the film too horrific to handle. Many thanks to pioneer shclockmeister William Castle for that idea. On top of that, you couldn't have a premiere without spotlights, limousines and tuxedos.

Just two weeks before the premiere, we finally saw what was then still called

Book of the Dead

in a local theater, late at night, on the big screen. The blowup looked good -- really good.

As I watched the 35mm images flicker in front of me, the thought rolling around in my head was,

Crazy, man, crazy.

We had laughed in the face of disaster and pulled it off. It was one of the few times in this odyssey when we had a feeling of accomplishment. Sure, it wasn't sold yet, but at least the current crisis was over.

Turnout for the premiere exceeded our expectations. About a thousand curious relatives, investors and ex-high school pals seemed to enjoy themselves immensely and whooped it up in

almost

all of the right places. Essentially a melodrama,

Evil Dead

walked a very fine line -- combine inexperienced actors with a primitive script and you're bound to get some unexpected laughs. We were happy to have any reaction at all.

Shortly after the show, we were told that an elderly woman wanted to see the filmmakers in the lobby right away. The screening was open to the public, so we figured we were going to get an earful.

"Did you fellows make this picture?" the octogenarian asked, in a tone that was hard to read.

"Uh, yes, ma'am," Sam replied.

"I just want to tell you boys that I was having such a bad day today. I saw the ad for your film and I thought I should get out and see what it was. Well, I'm glad I did, because now I feel great and I just wanted to thank you for it!"

Thus began our own "test-screening" process. We knew that the audience at the premiere was a deck stacked in our favor. We had to try

Evil Dead

in front of a pure audience and see if it still played. The decision was an immediate one -- take it to Michigan State University.

Screenings at the State Theater at MSU proved that the film

did

play -- the rowdier the audience the better. The one thing

Evil Dead

did was dish out the gore -- by the shovelful.

22

BIRTH OF A SALESMAN

In a rudderless search for a distribution deal, we showed our film to any man, woman or child for advice. The first targets were filmmakers, just to get sage advice about the do's and don'ts of the big "D."

"Well, you didn't fuck up, but you didn't do great either," came the assessment of an exploitation filmmaker. "It's really crude."

From there, we progressed to booking agents, exhibitors, subdistributors, packaging agents and lawyers. As helpful as they were, we began to get the impression that we'd be lucky to get any deal at all and that we should take what we could get.

We dragged a print to larger distributors on both coasts and in Canada, but the reaction was the same: unanimous disinterest.

"Your picture is pretty bloody," said a distributor. "Have you submitted it for a rating?"

"Well, no... not exactly."

"Cause if it can't get rated, you're shit out of luck."

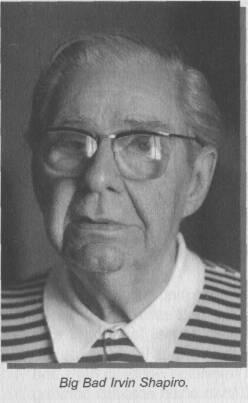

We needed help. Eventually, the name of a sales agent surfaced: Irvin Shapiro.

After doing some research, we saw that his company, Films Around the World, was connected to George Romero's early films. If this man was representing the filmmaker who brought the world

Night of the Living Dead,

he might just be the right guy for us.

Irvin Shapiro had lived a full life before we ever met him. As a young man in the 1920s, he handled the publicity for

Battleship Potemkin

by filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. Seeing an opportunity to sell foreign films to the U.S., Irvin became one of the founders of the Cannes Film Market. He was also one of the first entrepreneurs to buy television rights to films and was involved with the company Screen Gems. Irvin often enjoyed pointing out a painting by Picasso, hanging on his apartment wall, that he had traded the young painter for a bottle of wine.

Irvin had been around.

On December 10, 1981, we screened our film for this living legend. As the lights came up in the screening room, Irvin cracked a smile.

"It ain't

Gone with the Wind,

but I think we can make some money with it. Of course, we're gonna have to change the title. If you call it

Book of the Dead,

people are gonna think they have to read for ninety minutes. I think we can do better."

Revelation #28c:

Making a film and selling it are completely different birds.

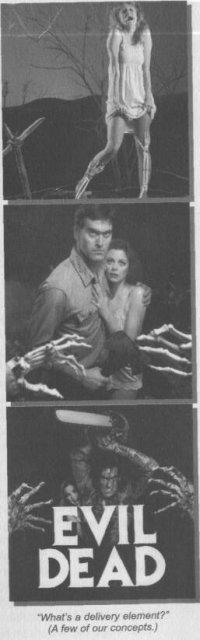

Back in Ferndale, we kicked some new names around. Irvin sent some ideas to us and we sent some back to him. Among the classics on the list were:

- Book of the Dead (the original)

- Blood Flood

- Fe-Monsters

- 101% Dead

- Death of the Dead

- The Evil Dead Men and the Evil Dead Women

- Evil Dead

Evil Dead

emerged as the

least worst

of the bunch. I recall thinking at the time that it was a piss-poor title, but changing it turned out to be the easy part.

"Where are your delivery elements?" Irvin asked.

Rob, Sam and I exchanged dumb looks.

"What's a delivery element?"

"The lab elements you need to sell your picture around the world."

"Like?"

"Like stills, a foreign textless, an M&E, a dialogue continuity, an inter-positive..."

This was a depressing prospect, because it led to the possibility that we'd have to scrape together even more money -- a feat I didn't think we could do.

Fortunately for us, Irvin Shapiro was one of the few honorable men in the film business -- his company fronted the necessary funds to create these delivery elements.

What followed was a lesson in sales from the Grand Master.

MADISON AVENUE IN DETROIT

In order to sell our film around the world, we had to provide not only the film but the technical tools necessary for foreign distributors to rerecord dialogue in a different language, change the title on the print and make a new poster. Even if your film was marketable, you couldn't close a deal without these items -- and if you couldn't close, you couldn't collect money to pay back the investors.