Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (2 page)

Read Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) Online

Authors: Michael Freeden

Michael Freeden

A Very Short Introduction

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford

OX

2 6

DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

© Michael Freeden 2003

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published as a Very Short Introduction 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 0-19-280281-X

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by RefineCatch Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

Printed in Great Britain by

TJ International Ltd., Padstow, Cornwall

1 Should ideologies be ill-reputed?

2 Overcoming illusions: how ideologies came to stay

3 Ideology at the crossroads of theory

4 The struggle over political language

5 Thinking about politics: the new boys on the block

6 The clash of the Titans: the macro-ideologies

7 Segments and modules: the micro-ideologies

8 Discursive realities and surrealities

9 Stimuli and responses: seeing and feeling ideology

10 Conclusion: why politics can’t do without ideology

References and further reading

1

“Congratulations! What got you here is your total lack of commitment to any ideology”

by Schwadron, April 1983

© Punch Ltd.

2

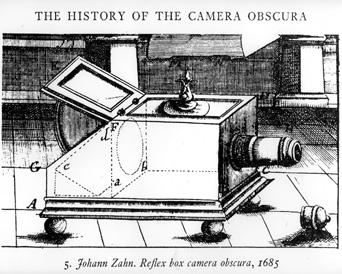

Camera obscura, 1685 Private collection/Bridgeman

Art Library

3

Karl Mannheim

© Luchterhand

4

Antonio Gramsci

© Farabolofoto, Milan

5

Louis Althusser

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

6

Man Controller of the Universe

, fresco, 1934 (detail), by Diego Rivera

© 2003 Bank of Mexico, Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Photo

© Museum of the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico/Corbis

7

This is the Road

, 1950, cartoon by David Low

© Evening Standard

8

Marx and Engels get hopelessly lost on a ramble, cartoon by Martin Rowson

© Martin Rowson. From M. Rowson and K. Killane,

Scenes from the Lives of the Great Socialists

, Grapheme Publications, London, 1983

9

Concentric Rinds

, 1953, by M. C. Escher

© 2003 Cordon Art B.V., Baarn, The Netherlands. All rights reserved.

10

Ideologies alter cases

, 1947, cartoon by David Low

© Evening Standard/Centre for the Study of Cartoons & Caricature, University of Kent, Canterbury

11

The Re-thinker

, 1953, cartoon by David Low

© The Guardian

12

The American Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1776

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

13

A Nazi Nuremberg rally, still from Leni Riefenstahl’s

Triumph of the Will

, 1934

The Kobal Collection

14

The First of May

, 1920, Bolshevik poster by N. M. Kochergin

The publisher and the author apologize for any errors or omissions in the above list. If contacted they will be pleased to rectify these at the earliest opportunity.

Should ideologies be ill-reputed?

Ideology is a word that evokes strong emotional responses. On one occasion, after I had finished a lecture that emphasized the ubiquity of political ideologies, a man at the back of the audience got up, raised himself to his full height and, in a mixture of affrontedness and disdain, said: ‘Are you suggesting, Sir, that I am an ideologist?’ When people hear the word ‘ideology’, they often associate it with ‘isms’ such as communism, fascism, or anarchism. All these words do denote ideologies, but a note of caution must be sounded. An ‘ism’ is a slightly familiar, faintly derogatory term – in the United States even ‘liberalism’ is tainted with that brush. It suggests that artificially constructed sets of ideas, somewhat removed from everyday life, are manipulated by the powers that be – and the powers that want to be. They attempt to control the world of politics and to force us into a rut of doctrinaire thinking and conduct. But not every ‘ism’ is an ideology (consider ‘optimism’ or ‘witticism’), and not every ideology is dropped from a great height on an unwilling society, crushing its actually held views and convictions and used as a weapon against non-believers. The response I shall give my perplexed man at the back in the course of this short book is the one put by Molière in the mouth of M. Jourdain, who discovered to his delight that he had been speaking prose all his life. We produce, disseminate, and consume ideologies all our lives, whether we are aware of it or not. So, yes, we are all ideologists in that we have understandings of the political environment of which we

are part, and have views about the merits and failings of that environment.

Imagine yourself walking in a city. Upon turning the corner you confront a large group of people acting excitedly, waving banners and shouting slogans, surrounded by uniformed men trying to contain the movement of the group. Someone talks through a microphone and the crowd cheers. Your immediate reaction is to decode that situation quickly. Should you flee or join, or should you perhaps ignore it? The problem lies in the decoding. Fortunately, most of us, consciously or not, possess a map that locates the event we are observing and interprets it for us. If you are an anarchist, the map might say: ‘Here is a spontaneous expression of popular will, an example of the direct action we need to take in order to wrest the control of the political away from elites that oppress and dictate. Power must be located in the people; governments act in their own interests that are contrary to the people’s will.’ If you are a conservative, the map may say: ‘Here is a potentially dangerous event. A collection of individuals are about to engage in violence in order to attain aims that they have failed, or would fail, to achieve through the political process. This illegitimate and illegal conduct must be contained by a strong police grip on the situation. They need to be dispersed and, if aggressive, arrested and brought to account.’ And if you are a liberal, it may say: ‘Well-done! We should be proud of ourselves. This is a perfect illustration of the pluralist and open nature of our society. We appreciate the importance of dissent; in fact, we encourage it through instances of free speech and free association such as the demonstration we are witnessing.’

Ideologies, as we shall see, map the political and social worlds for us. We simply cannot do without them because we cannot act without making sense of the worlds we inhabit. Making sense, let it be said, does not always mean making good or right sense. But ideologies will often contain a lot of common sense. At any rate, political facts never speak for themselves. Through our diverse ideologies, we provide competing interpretations of what the facts

might mean. Every interpretation, each ideology, is one such instance of imposing a pattern – some form of structure or organization – on how we read (and misread) political facts, events, occurrences, actions, on how we see images and hear voices. Ideological maps do not represent an objective, external reality. The patterns we impose, or adopt from others, do not have to be sophisticated, but without a pattern we remain clueless and uncomprehending, on the receiving end of ostensibly random bits of information without rhyme or reason.

1. A reward or an ironic comment?

Why, then, is there so much suspicion and distrust of ideologies? Why are they considered to be at the very least alien caricatures, if not oppressive ideational straitjackets, that need to be debunked and dismantled to protect a society against brainwashing and dreaming false dreams? There has rarely been a word in political language that has attracted such misunderstanding and opprobrium. We need to clear away some debris in order to appreciate that, to the contrary, there are very few words that refer to such an important and central feature of political life.

In discussing ideologies, this book will mainly refer to political ideologies and will argue that ideologies are political devices. When ideology is used in other senses – such as the ideology of the impressionists or of Jane Austen – the word is borrowed or generalized to indicate the much vaguer notion of the cultural ideas guiding the field or steering the practitioner in question. One problem with the term ‘ideology’ is that too many of its users have shied away from injecting it with a reasonably precise, useful, and illuminating meaning.