I Have Landed (51 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Moreover, the assertion of this evolutionary linkage during the past twenty years does not mark a stunningly new and utterly surprising discovery, but rather reaffirms an old idea that seemed patently obvious to many paleontologists in Darwin's day (notably to T. H. Huxley, who defended the argument in several publications), but then fell from popularity for a good reason based on an honest error.

The detailed anatomical correspondence between

Archaeopteryx

, the earliest toothed bird of Late Jurassic times, and the small running dinosaurs now known as maniraptors (and including such popularized forms as

Deinonychus

and

Troodon)

can hardly fail to suggest a close genealogical relationship. But following Huxley's initial assertion of an evolutionary link, paleontologists reached the false conclusion that all dinosaurs had lost their clavicles, or collar-bonesâa prominent component of bird skeletons, where the clavicles enlarge and fuse to form the furcula, or wishbone. Since complex anatomical structures, coded by numerous genes working through intricate pathways of development, cannot reevolve after a complete loss, the apparent absence of clavicles in dinosaurs seemed to preclude a directly ancestral status to birds, though most paleontologists continued to assert a relationship of close cousinhood.

The recent discovery of clavicles in several dinosaursâincluding the forms closest to birdsâimmediately reinstated Huxley's old hypothesis of direct evolutionary descent. I don't mean to downplay the significance of a firm resolution for the evolutionary relationship between birds and dinosaurs, but for sheer psychological punch, the revivification of an old and eminently sensible idea cannot match the impact of discovering a truly pristine and almost shockingly unexpected item in nature's factual arsenal.

But I throw my iciest pitcher of water (a device to open eyes wide shut, not an intended punishment) into the face of a foolish claim almost invariably featuredâusually as a headlineâin any popular article on the origin of birds: “Dinosaurs didn't die out after all; they remain among us still, more numerous than ever, but now twittering in trees rather than eating lawyers off John seats.”

This knee-jerk formulation sounds right in the superficial sense that buttresses most misunderstandings in science, for the majority of our errors reflect false conventionalities of hidebound thinking (conceptual locks) rather than failures to find the information (factual lacks) that could resolve an issue in purely observational terms. After all, if birds evolved from dinosaurs (as they

did) and if all remaining dinosaurs perished in a mass extinction triggered by an impacting comet or asteroid 65 million years agoâwell, then, we must have been wrong about dinosaurian death and incompetence, for our latter-day tyrannosaurs in the trees continually chirp the New Age message

of Jurassic Partk

, life finds a way. (In fact, as I write this paragraph, a mourning dove mocks my mammalian pretensions in a minor key, from a nest beneath my air conditioner.

Sic non transit gloria mundi!)

Only our largely unconscious bias for conceiving evolution as a total transformation of one entity into a new and improved model could buttress the common belief that canonical dinosaursâthe really big guys, in all their brontosaurian bulk or tyrannosaurian terrorâlive on as hawks and hummingbirds. For we do understand that most species of dinosaurs just died, plain and simple, without leaving any direct descendants. Under a transformational model, however, any ancestral bird carries the legacy of all dinosaurs at the heart of its courageous persistence, just as the baton in a relay race embodies all the efforts of those who ran before.

However, under a corrected branching model of evolution, birds didn't descend from a mystical totality but only from the particular little bough that generated an actual avian branch. The dinosaurian ancestors of birds lie among the smallest bipedal carnivores (think of little

Compsognathus

, tragically mistaken for a cute pet in the sequel

to Jurassic Party

âcreatures that may be “all dinosaur” by genealogy but that do not seem so functionally incongruous as progenitors of birds. Ducks as direct descendants of

Diplodocus

(a sauropod dinosaur of maximal length) would strain my credulity, but ostriches as later offshoots from a dinosaurian line that began with little

Oviraptor

(a small, lithe carnivore of less than human, and much less than ostrich, height) hardly strains my limited imagination.

As a second clarification offered by the branching model of evolution, we must distinguish similarity of form from continuity in descent: two important concepts of very different meaning and far too frequent confusion. The fact of avian descent from dinosaurs (continuity) does not imply the persistence of the functional and anatomical lifestyle of our culture's canonical dinosaurs. Evolution does mean change, after all, and our linguistic conventions honor the results of sufficiently extensive changes with new names. I don't call my dainty poodle a wolf or my car a horse-drawn carriage, despite the undoubted ties of genealogical continuity.

To draw a more complex but precise analogy in evolutionary terms: Mammals evolved from pelycosaurs, the “popular” group of sail-backed reptiles often mistaken for dinosaurs in series of stamps or sets of plastic monsters

from the past. But I would never make the mistake of claiming that

Dimetrodon

(the most familiar and carnivorous of pelycosaurian reptiles) still exists because I am now typing its name, while whales swim in the sea and mice munch in my kitchen. In their descent from pelycosaurs, mammals evolved into such different creatures that the ancestral name, defined for a particular set of anatomical forms and functions, no longer describes the altered descendants. Moreover, and to reemphasize the theme of branching, pelycosaurs included three major subgroups, only two bearing sails on their backs. Mammals probably evolved as a branch of the third, sailless group. So even if we erroneously stated that pelycosaurs still lived because mammals now exist, we could not grant this status to a canonical sail-backed form, any more than we could argue for brontosaurian persistence because birds descended from a very different lineage of dinosaurs.

2.

A tidbit with feathers

. If birds evolved from small running dinosaurs, and if feathers could provide no aerodynamic benefit in an initial state of rudimentary size and limited distribution over the body, then feathers (which, by longstanding professional consensus and clear factual documentation, evolved from reptilian scales) must have performed some other function at their first appearance. A thermodynamic role has long been favored for the first feathers on the small-bodied and highly active ancestors of birds. Therefore, despite some initial skepticism, abetted by a few outlandish and speculative reconstructions in popular films and fiction, the hypothesis of feathered dinosaurs as avian ancestors gained considerable favor. Then, in June 1998, Ji Qiang and three North American and Chinese colleagues reported the discovery of two feathered dinosaurs from Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous rocks in China (“Two Feathered Dinosaurs from Northeastern China,”

Nature

393, 25 June 1998).

The subject has since exploded in both discovery and controversy, unfortunately intensified by the reality of potential profits previously beyond the contemplation of impoverished Chinese farmersâa touchy situation compounded by the lethal combination of artfully confected hoaxes and enthusiastically wealthy, but scientifically naïve, collectors. At least one fake (the so-called

Archaeoraptor)

has been exposed, to the embarrassment of

National Geographic

, while many wonderful and genuine specimens languish in the vaults of profiteers.

But standards have begun to coagulate, and at least one genusâ

Caudipteryx

(“feather-tailed,” by etymology and actuality)âholds undoubted status as a feathered runner that could not fly. And so at least until the initiating tidbit for this essay appeared in the August 17,2000, issue

of Nature

, one running dinosaur with utterly unambiguous feathers on its tail and forearms seemed to stand forth

as an ensign of Huxley's intellectual triumph and the branching of birds within the evolutionary tree of ground-dwelling dinosaurs. But the new article makes a strong, if unproven, case for an inverted evolutionary sequence, with

Caudipteryx

interpreted as a descendant of flying birds, secondarily readapted to a running lifestyle on terra firma, and not as a dinosaur in a lineage of exclusively ground-dwelling forms (T. D. Jones, J. O. Farlow, J. A. Ruben, D. M. Henderson, and W. J. Hillenius, “Cursoriality in Bipedal Archosaurs,”

Nature

406 [17 August 2000J).

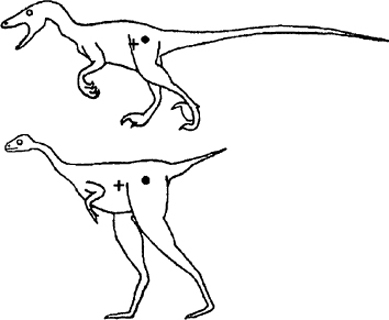

The case for secondary loss of flight rests upon a set of anatomical features that

Caudipteryx

shares with modern ground birds that evolved from flying ancestorsâa common trend in several independent lineages, including ostriches, rheas, cassowaries, kiwis, moas, and others. By contrast, lineages of exclusively ground-dwelling forms, including all groups of dinosaurs suggested as potential ancestors of birds, evolved different shapes and proportions for the same features. In particular, as the accompanying illustration shows, ground-running and secondarily flightless birdsâin comparison with small dinosaurs of fully terrestrial lineagesâtend to have relatively shorter tails, relatively longer legs, and a center of gravity located in a more forward (headward) position. By all three criteria, the skeleton

of Caudipteryx

falls into the domain of flightless birds rather than the space of cursorial (running) dinosaurs.

Jones and colleagues have presented an interesting hypothesis demanding further testing and consideration, but scarcely (by their own acknowledgment) a firm proof or even a compelling probability. Paleontologists have unearthed only a few specimens

of Caudipteryx

, none complete. Moreover, we do not know the full potential for ranges of anatomical variation in the two relevant lifestyles.

Perhaps

Caudipteryx

belonged to a fully terrestrial lineage of dinosaurs that developed birdlike proportions for reasons unrelated to any needs or actualities of flight.

The flightless Cretaceous bird

Caudipteryx

(bottom) was closer in proportions to a modern emu or ostrich than to a bipedal dinosaur (top). The plus signs mark the torsos' centers of gravity, and hip joints are indicated by dots

.

I do not raise this issue here to vent any preference (for I remain neutral in a debate well beyond my own expertise, and I do regard the existence of other genera of truly feathered dinosaurs as highly probable, if not effectively proved).

15

Nor do I regard the status of

Caudipteryx

as crucial to the largely settled question about the dinosaurian ancestry of birds. If

Caudipteryx

belongs to a fully terrestrial lineage of dinosaurs, then its feathers provide striking confirmation for the hypothesis, well supported by several other arguments, that this defining feature of birds originated in a running ancestor for reasons unrelated to flight. But if

Caudipteryx

is a secondarily flightless bird, the general hypothesis of dinosaurian ancestry suffers no blow, though

Caudipteryx

itself loses its potential role as an avian ancestor (while gaining an equally interesting status as the first known bird to renounce flight).

Rather, I mention this tidbit to close my essay because the large volume of press commentary unleashed by the hypothesis of Jones and his colleagues showed me yet againâthis time for the microcosm of

Caudipteryx

rather than for the macrocosm of avian origins in generalâjust how strongly our trans-formational biases and our failure to grasp the reality of evolution as a branching bush distort our interpretations of factual claims easily understood by all. In short, I was astonished to note that virtually all these press commentaries reported the claim for secondary loss of flight in

Caudipteryx

as deeply paradoxical and stunningly surprising (even while noting the factual arguments supporting the assertion with accuracy and understanding).

In utter contrast, the hypothesis of secondary loss of flight in

Caudipteryx

struck me as interesting and eminently worthy of further consideration but also as entirely plausible. After all, numerous lineages of modern birds have lost their ability to fly and have evolved excellent adaptations for running in a rapid and sustained manner on the ground. If flightlessness has evolved in so many independent lineages of modern birds, why should a similar event surprise us merely by occurring so soon after the origin of birds? (I might even speculate that Cretaceous birds exceeded modern birds in potential for evolutionary loss of flight, for birds in the time of

Caudipteryx

had only recently evolved as flying forms from running ancestors. Perhaps these early birds still retained

enough features of their terrestrial ancestry to facilitate a readaptation to ground life in appropriate ecological circumstances.) Moreover, on the question of timing in our admittedly spotty fossil record,

Archaeopteryx

(the first known bird) lived in Late Jurassic times, while

Caudipteryx

probably arose at the beginning of the subsequent Cretaceous periodâplenty of time for a flying lineage to redeploy one of its species as a ground-dwelling branch.