How to Live (31 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Writers like Diderot and Rousseau were drawn not only to the “cannibal” Montaigne, but to all the passages in which he wrote of simple and natural ways of life. The book in which Rousseau seems to have borrowed most from the

Essays

is

Émile

, a hugely successful pedagogical novel which changed the lives of a whole generation of fashionably educated children by promoting a “natural” upbringing. Parents and tutors should bring up children gently, he suggested, letting them learn about the world by following their own curiosity while surrounding them with opportunities for travel, conversation, and experience. At the same time, like little Stoics, they should also be inured to tough physical conditions. This is clearly traceable to Montaigne’s essay on education, although Rousseau mentions Montaigne only occasionally in the book, usually to attack him.

He insults Montaigne again at the outset of his autobiography, the

Confessions

—a work which might be thought to owe something to Montaigne’s project of self-portraiture. In his original preface (often omitted in later editions), Rousseau wards off such accusations by writing, “I place Montaigne foremost among those dissemblers who mean to

deceive by telling the truth. He portrays himself with defects, but he gives himself only lovable ones.” If Montaigne, misleads the reader, then it is not he but Rousseau who is the first person in history to write an honest and full account of himself.

This frees Rousseau to say, of his own book, “This is the only portrait of a man, painted exactly according to nature and in all its truth, that exists and will probably ever exist.”

The works do differ, and not just because the

Confessions

is a narrative, tracing a life from childhood on rather than capturing everything at once as the

Essays

does. There is also a difference of purpose. Rousseau wrote the book because he considered himself so exceptional, both in brilliance and sometimes in wickedness, that he wanted to capture himself before this unique combination of features was lost to the world.

I know men.

I am not made like any that I have seen; I venture to believe that I was not made like any that exist … As to whether Nature did well or ill to break the mold in which I was cast, that is something no one can judge until after they have read me.

Montaigne, by contrast, saw himself as a thoroughly ordinary man in every respect, except for his unusual habit of writing things down. He “bears the entire form of the human condition,” as everyone does, and is therefore happy to cast himself as a mirror for others—the same role he bestows on the Tupinambá. That is the whole point of the

Essays

. If no one could recognize themselves in him, why would anyone read him?

Some contemporaries noticed suspicious similarities between Rousseau and Montaigne. Rousseau was overtly accused of theft: a tract by Dom Joseph Cajot, bluntly called

Rousseau’s Plagiarisms on Education

, opined that the only difference was that Montaigne gushed less than Rousseau and was more concise—surely the only time the latter quality has ever been attributed to Montaigne. Another critic, Nicolas Bricaire de la Dixmerie, invented a dialogue in which Rousseau admits to having copied ideas from Montaigne, but argues that they have nothing in common because he writes “in inspiration” while Montaigne writes “coldly.”

Rousseau lived in an era when gushing, inspiration, and heat were admired. They meant, precisely, that you were in touch with “Nature,”

rather than being a slave to the frigid requirements of civilization. You were savage and sincere; you had cannibal chic.

Eighteenth-century readers who embraced Montaigne for his praise of the Tupinambá, and for all his writings on nature, were gradually blossoming into full Romantics—a breed who would dominate the late years of that century and the early years of the following one. And Montaigne would never be quite the same again once the Romantics had finished with him.

From its beginning in the form of a mildly rebellious, open-minded answer to the question of living well, “Wake from the sleep of habit” gradually metamorphosed into something much more rabble-rousing and even revolutionary. After Romanticism, it would no longer be easy to see Montaigne as a cool, gracious source of Hellenistic wisdom. From now on, readers would persist in trying to warm him up. He would, for evermore, have a wild side.

RAISING AND LOWERING THE TEMPERATURE

I

N MANY WAYS

, readers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries found it easy to like the Montaigne they constructed for themselves.

As well as appreciating his praise for the Americans, they responded to his openness about himself, his willingness to explore the contradictions of his character, his disregard for convention, and his desire to break out of fossilized habits. They liked his interest in psychology, especially his sense of the way different impulses could coexist in a single mind. Also—and they were the first generation of readers to feel this way in great numbers—they enjoyed his writing style, with all its exuberant disorder. They liked the way he seemed to blurt out whatever was on his mind at any moment, without pausing to set it into neat array.

Romantic readers were particularly taken by Montaigne’s intense feeling

for La Boétie, because it was the only place where he showed strong emotion. The tragic ending of the love story, with La Boétie’s death, made it more beautiful. Montaigne’s simple answer to the question of why they loved each other—“Because it was he, because it was I”—became a catchphrase, denoting the transcendent mystery in all human attraction.

In her autobiography, the Romantic writer George Sand related how she became obsessed with Montaigne and La Boétie in her youth, as the prototype of spiritual friendship she herself longed to find—and did, in later life, with writer friends such as Flaubert and Balzac. The poet Alphonse de Lamartine felt similarly. In a letter, he wrote of Montaigne: “All that I admire in him is his friendship for La Boétie.” He had already borrowed Montaigne’s formula to describe his own feelings in an earlier letter to the same friend: “Because it is you, because it is I.” He embraced Montaigne himself as such a companion, writing of “friend Montaigne, yes: friend.”

The new highly charged or heated quality of such responses to Montaigne can be measured in the increase, during this era, in pilgrimages to his tower.

Visitors called on the Montaigne estate, drawn by curiosity, but once there they lost their heads; they stood rapt in meditation, feeling Montaigne’s spirit all around them like a living presence. Often, they felt almost as though they had

become

him, for a few moments.

There had been little of this in previous centuries. Montaigne’s descendants lived at the estate until 1811, and for most of this time no one interfered with them while they converted the ground floor of the tower into a potato store and the first-floor bedroom sometimes to a dog kennel, sometimes to a chicken coop. This changed only after a trickle of early Romantic visitors turned into a regular flow, until eventually the potatoes and chickens gave way to an organized re-creation of his working environment.

This all seemed self-explanatory to the Romantics. Naturally, if you responded to Montaigne’s writing, you must want to be there in person: to gaze out of his window at the view he would have seen every day, or to hover behind the place where he might have sat to write, so you could look down and almost see his ghostly words appear before your eyes. Taking no account of the hubbub that would really have been going on in the courtyard below, and probably in his room too, you were free to imagine

the tower as a monastic cell, which Montaigne inhabited like a hermit. “Let us hasten to cross the threshold,” wrote one early visitor, Charles Compan

, of the tower library:

If your heart beats like mine with an indescribable emotion; if the memory of a great man inspires in you this deep veneration which one cannot refuse to the benefactors of humanity—enter.

The pilgrimage tradition outlived the Romantic era proper. When the marquis de Gaillon wrote of his visit to the tower in 1862, he summoned up the pain of departure in lover’s language:

But at last one must leave this library, this room, this dear tower. Farewell, Montaigne! for to leave this place is to be separated from you.

The problem with all such passionate swooning into Montaigne’s arms has always been Montaigne himself. To fantasize about him in this way is to set oneself at odds with his own way of doing things. Blocking out parts of the

Essays

that interfere with one’s chosen interpretation is a timeless activity, but the hot-blooded Romantics had a harder task than most. They were constantly brought up against things like this:

I have no great experience of these vehement agitations, being of an indolent and sluggish disposition.

I like temperate and moderate natures.

My excesses do not carry me very far away. There is nothing extreme or strange about them.

The most beautiful lives, to my mind, are those that conform to the common human pattern, with order, but without miracle and without eccentricity.

The poet Alphonse de Lamartine was one such frustrated reader. When he first came across Montaigne he hero-worshiped him, and kept a volume of the

Essays

always in his pocket or on his table so he could seize it whenever he had the urge.

But later he turned against his idol with equal vehemence: Montaigne, he now decided, knew nothing of the real miseries of life. He explained to a correspondent that he had only been able to love the

Essays

when he was young—that is, about nine months earlier, when he first began to enthuse about the book in his letters. Now, at twenty-one, he had been weathered by pain, and found Montaigne too cool and measured. Perhaps, he wondered, he might return to Montaigne many years later, in old age, when even more suffering had dried his heart. For now, the essayist’s sense of moderation made him feel positively ill.

George Sand also wrote that she was “not Montaigne’s disciple” when it came to his Stoical or Skeptical “indifference”—his equilibrium or

ataraxia

, a goal that had now gone out of fashion. She had loved his friendship with La Boétie, as the one sign of warmth, but it was not enough and she tired of him.

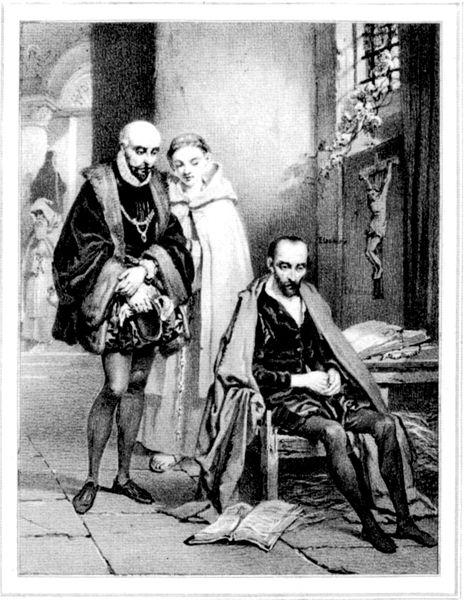

The worst sticking-point for Romantic readers was a passage in which Montaigne described visiting the famous poet Torquato Tasso in Ferrara, on his Italian travels in 1580.

Tasso’s most celebrated work, the epic

Gerusalemme liberata

, enjoyed immense success on its publication that same year, but the poet himself had lost his mind and was confined to a madhouse, where he lived in atrocious conditions surrounded by distressed lunatics. Passing through Ferrara, Montaigne called on him, and was horrified by the encounter. He felt sympathy, but suspected that Tasso had driven himself into this condition by spending too long in states of poetic ecstasy. The radiance of his inspiration had brought him to unreason: he had let himself be “blinded by the light.” Seeing genius reduced to idiocy saddened Montaigne. Worse, it irritated him. What a waste, to destroy oneself in this way! He was aware that writing poetry required a certain “frenzy,” but what was the point of becoming so frenzied that one could never write again? “The archer who overshoots the target misses as much as the one who does not reach it.”

Looking back at two such different writers as Montaigne and Tasso, and admiring both, Romantics were prepared to go along with Montaigne’s

belief that Tasso had blown his own mind with poetry. They could understand Montaigne’s sadness about it. What they could neither understand nor forgive was his irritation. Romantics did blinding brilliance; they did melancholy; they did intense imaginative identification. They did not do irritation.