How the French Invented Love (42 page)

Read How the French Invented Love Online

Authors: Marilyn Yalom

Sauder places the text itself at the center of the film. The students read it aloud or recite it by heart. From time to time, they comment on the words they have pronounced. Sauder remarks: “I remember a conversation about love with one of the young girls, Aurore, when she said, in reference to the novel but also to her own life, ‘When one loves, there are no longer any limits.’ I had the impression that I was hearing her heart beat when she said that.”

The students understood

La Princesse de Clèves

as “a story of passionate love” that they could carry into their personal lives and discuss with their families and friends. As they acted in the film, they sensed how much they were emotionally and intellectually transformed by it. A seventeen-year-old named Abou recognized himself in the code of honor that reigned in the French court centuries before he was born, despite the glaring difference in social milieu.

Surprisingly, all the young people appreciated the advice of the princess’s mother, Mme de Chartres, who would prefer death rather than see her daughter embark on an adulterous affair. They understood how important it was for the mother to inculcate a sense of family honor in her female progeny. The novel allowed them to talk to their own mothers about love, under the cover of

La Princesse de Clèves

.

Little by little, as a spectator, I became totally immersed in the lives of these young people with café-au-lait skins and features different from the conventional white faces one thinks of as French. I saw how they became one with a story about love born in a time and place so unlike their own. It was further proof to me, if ever I needed it, that words can continue to live long after they are written, and that love is recognizable from one generation to the next, however unfamiliar its wrappings. I would give this film four stars.

On the plane home from France, I saw two films by Claude Lelouch,

Roman de gare

(2007) and

Ces amours-là

(2011). I have been a Lelouch fan ever since I saw his breakthrough film

Un homme et une femme

(

A Man and a Woman

), which won the Palme d’Or at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival, as well as the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. At that time, as the mother of three small children with a fourth yet to come, I especially appreciated the familiarity that develops between the future lovers, both widowed, around their children attending the same boarding school. It was one of the first films I had ever seen that brought the lovers’ children into the picture. I liked the slow disclosing of their past marital histories. I was particularly struck by the sensitive bedroom scene that shows the woman (played by Anouk Aimée) unable to continue with their lovemaking because she is still holding on to the memory of her dead husband. Usually cinematic lovemaking is presented as something that happens easily, leading to enormous female orgasms, without any suggestion that it can be problematic. The film was a winner then and still is.

Over forty years later, Claude Lelouch is still making films centered on love.

Roman de gare

(

Crossed Tracks

) is a quirky mystery story about a woman novelist (played by the inimitable Fanny Ardant), her ghostwriter (the smash-nosed Dominique Pinon), and an airhead hairdresser and sometime prostitute who drags the ghostwriter haplessly into her family drama. The plot is clever, the acting superb, the novelist gets her just deserts, and the ghostwriter ends up with the wayward woman. As in so many films, a tender kiss provides satisfying closure to the spectacle, even if one has few illusions about the future of the couple. Let’s say, two and a half stars.

Lelouch’s 2011

Ces amours-là

(

What War May Bring

) rejoices in love on an epic scale. Focusing on the successive loves of just one woman named Ilva, it begins with her passionate affair with a German officer during the Occupation. On the one hand, the officer saves Ilva’s father from execution as a hostage; on the other, Ilva’s association with the German ultimately brings about her father’s death at the hands of French partisans. When the Germans are finally forced out of Paris, she risks the fate of many publicly humiliated Frenchwomen, shorn of their hair as penance for their German lovers. Ilva is saved by two American soldiers—one white, one black. Since she can’t choose between them, she goes to bed with both of them. Their spirited ménage à trois has a decidedly French amoralistic exuberance, until the plot turns tragic for one of the two men. Married to the other—I won’t tell you which one—Ilva is unable to find happiness as an American bride. She returns to France for a third love experience, this time with a Frenchman who also turns out to be her savior. The plot is complicated. Are we expected to pass judgment on Ilva, who falls in love too easily and never foresees the negative consequences of her acts? Perhaps. Yet the film ends on an upbeat note. Lelouch situates it within the entire history of cinema, and particularly within his own oeuvre, from which numerous scenes flash by in the last minutes of the film. He offers us a jubilant finale created from diverse images of love

à la française

, all underscored by the vibrant strains of American popular music. Lelouch seems to be saying that whatever gruesome political realities we live through, whatever moral issues we face, passionate love will always endure.

Ces amours-là

is a frank celebration of love in an age when love itself, treasured for centuries, is now under attack. I give it three stars.

As I unpacked from another memorable French trip, I had no way of anticipating how much the French discourse on love would change during the next few months.

P

LUS ÇA CHANGE, PLUS C’EST LA MÊME CHOSE.

T

HE MORE THINGS CHANGE, THE MORE THEY STAY THE SAME.

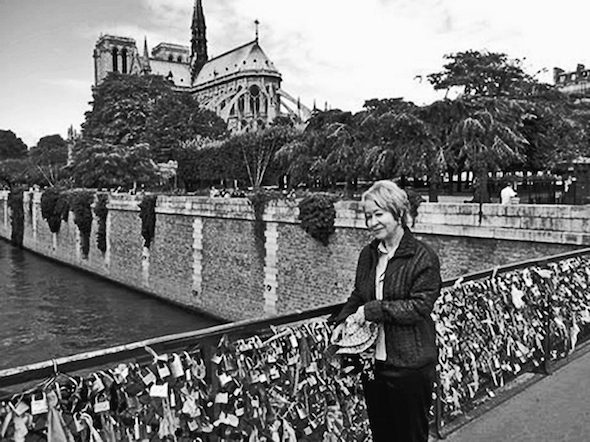

Padlocks attached by lovers to grille on the Pont de l’Archevêché over the Seine, 2011. Author’s photographs.

I

n May 2011, France was jolted out of its age-old indulgence toward all forms of erotic behavior by the arrest of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, charged with having sexually assaulted a New York hotel housekeeper. Since Strauss-Kahn was the front-runner Socialist Party candidate for the 2012 presidential elections and considered nearly a shoo-in against the incumbent Nicolas Sarkozy, the shock that ran through France was seismic. It was one thing to have been a known womanizer, like so many French presidents, and quite another to have been arrested under suspicion of rape.

As a prominent politician, Strauss-Kahn had already been accused once before, in 2003, of swerving from gallantry to coercion, according to a young journalist’s complaint that he had attacked her during an interview. At that time, she didn’t press charges because her mother, a Socialist Party official, persuaded her not to. Also, during his tenure as managing director of the International Monetary Fund, he had a brief affair with a subordinate employee in 2008 and was subsequently rebuked by the IMF, though not dismissed because the affair was judged to be consensual. Through all of this, Strauss-Kahn’s third wife, Anne Sinclair, stood loyally at his side.

In the wake of the 2011 New York scandal, the French began to question the conspiracy of silence surrounding the sexual indiscretions of their public figures. They had to consider the allegation that some men, especially powerful ones, not only expect erotic favors from their subordinates but sometimes use strong-arm methods to obtain their ends. Eventually the charges against Strauss-Kahn were dropped because it was discovered that his accuser had lied on several important issues, but French feminists were not about to forget this unsavory story: they seized the opportunity to make public pronouncements on the line between flirting and sexual aggression and hoped their clamor would cause men to think twice before forcing women into the bedroom.

This is obviously not the tawdry note I favor for the finale of a book on love. Coerced sex is not love. It is a form of violence against women, and sometimes against men. And yet, such is the complicated relationship between sex and love that the French have been known to conflate the two, and even to whitewash sexual acts committed through intimidation or brute force. The first reaction of a few French males to the Strauss-Kahn affair was to treat it as

une imprudence, comment dire: un troussage de domestique

—an imprudent act, like having sex with the maid.

1

Certainly there is a long history in France, as in other countries, of male employers taking advantage of female domestics. This can lead to pregnancies and bastard children, as in the case of Violette Leduc, but it rarely leads to love.

There has always been a cynical promotion of carnal pleasure in France, alongside the history of romantic love, ever since the latter was invented by twelfth-century troubadours. Consider

La clef d’amors

(

The Key to Love

), a medieval advice manual that even condones force. Here’s some of its graphic counsel to men: “Once you have pressed your lips to hers / (Despite her long and loud demurs), / You must not stop at mere embrace: / Push on, pursue the rest apace.” Like men in all centuries, the author condones the use of force by blithely assuming that the lady “really hopes you ignore / Her protests.”

2

This is the same mentality motivating Valmont in

Les liaisons dangereuses

. He will have his way with Madame de Tourvel regardless of the pain it will cause her. But in the end, his “victory” is also hers, for despite his denials, he falls in love with her. It is left to Madame de Merteuil to enlighten Valmont about the true nature of his feelings, and to unleash destructive justice.

For hundreds of years, sexual license in France was kept under loose control by the rules of courtly love, gallantry, and royal decree. As early as the fourteenth century, kings appointed their own official mistresses and looked the other way when members of their courts took lovers outside of marriage. Rarely did a king of France condemn the erotic adventures of his courtiers, unless that person tread upon territory the king himself coveted. Remember Henri IV, Bassompierre, and Mademoiselle de Montmorency in chapter 2. Even though the church took a different point of view and condemned any form of extramarital sex—sometimes even that of the royals—France has always been a country where sex has not only been tolerated but generally prized as part of the national character.

Love without sex is not a French invention. Leave it to the English, the Germans, and the Italians to project human love into the sphere of the angels. There is no French counterpart to Dante’s divine Beatrice, Goethe’s Eternal Feminine, or the British Angel in the House. Instead, sexually vibrant women in life and literature—such as Héloïse, Iseult, Guinevere, Diane de Poitiers, Julie de Lespinasse, Rousseau’s Julie, Madame de Staël, George Sand, Madame Bovary, Colette, Simone de Beauvoir, and Marguerite Duras—have provided models for women in love. For men, Lancelot, Tristan, certain kings (notably François I, Henri II, Henri IV, Louis XIV, and Louis XV), Saint-Preux, Valmont, Lamartine, Julien Sorel, Musset, French movie stars and presidents have offered a conjoint set of virile models.

Yet, despite their emphasis on physical pleasure, most French have always understood love as something more than mere sexual satisfaction. Love privileges tender feelings, inspires esteem and fidelity, has the potential for uniting lovers permanently in enduring liaisons or lifelong marriage. Two such eighteenth-century unions that I haven’t talked about (for lack of space) were that of Voltaire and Madame du Châtelet, an exceptionally distinguished pair who enjoyed a very long, multifaceted liaison, and that of the Comtesse de Sabran and the Chevalier de Boufflers, two lovers who surmounted huge obstacles for twenty years before they were able to marry.

3

Loving marriages and liaisons that endured over time were probably as difficult to maintain in the past as they are today. George Sand called love a “miracle” requiring the surrender of two wills, so as to mingle and become one. She went so far as to compare love to religious faith, in that both share the ideal of eternity. Well, eternity is a long time. Let us say that Sand held on to her idealistic vision of lasting love for the decade she spent with Chopin and then for the following fifteen years she shared with Manceau. To remain faithful to two men, successively, over a period of twenty-five years was not such a bad record for Sand.