How (37 page)

Authors: Dov Seidman

Informed acquiescence culture, with its hierarchical separation of functions, actually reinforces this gap. One department—say, compliance—might issue proscriptive regulations controlling what you can and can’t say to the marketplace about your products and competition, and another—say, the sales department—might give guidance about what moves the product. In the middle, a salesperson is left to bridge the gap on her own. “I can’t

say

that,” she might think, “but the notion moves product. Perhaps I can

intimate

it instead.” When something is expressed as a self-governing value, by contrast, no one tries to split the middle, because there is no middle. The value—in the salesperson’s case, truthfulness—provides a clear

should

that is unambiguous. And she doesn’t have to say, “I’ll go check with my boss to see what I can say or do.” She can act on her belief, immediately, efficiently, and rapidly. There is no gap, either personally or institution-ally, between the individual and the best behavior (see

Figure 10.1

).

Values speak to the higher self. They have the power to inspire and not just motivate. They breed belief. Values-based self-governance, in turn, performs a remarkable double duty: It controls unwanted behavior while simultaneously inspiring higher conduct. In this way, values are actually a more efficient determiner of HOW we do what we do than are rules. When we embrace a value and weld it to our behavior, we believe in what we do. Business defined in values terms is business done for a higher purpose, inspired for the greater good. A person aligned with a company value will be less likely to betray that value, because to do so does not just break a company policy; it betrays the self. At the root of these cultures lies shared values, the HOWS that guide every interaction.

Business has become really good about safety since the early 1990s, in great measure because, perhaps without realizing it, it shifted safety from a set of rules and programs to a part of its core values system, and then found a way to transmit those values throughout the workforce. In other words, it changed safety from a vertical silo of WHAT into a horizontal force of HOW that powered every part of the operation, shifting it from a set of rules to a part of culture. And it succeeded. From 1992 to 2002, U.S. workplace fatalities declined 11 percent, and injuries and illness in private industry declined a remarkable 34 percent, not from more safety cops, but from more safety belief.

5

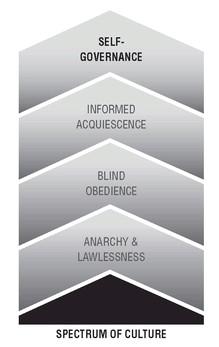

Anarchy and lawlessness, blind obedience, informed acquiescence, and values-based self-governance represent the four basic types of group culture, but almost no company, team, or group is wholly one or another; they often contain bits of each in different measures. When that top salesperson decides that expense limits do not apply to him and orders the most expensive bottle of wine on the menu at his dinner meeting, he in a sense indulges anarchic impulses. “Rules are not for me,” he seems to say. “I’ll get it done my way.” (Although such mavericks have a special place in the history of business, when most people organize to achieve something bigger than themselves they tend to embrace some sort of regulating system, so we will not focus much on anarchy and lawlessness for the purposes of this discussion.) When the boss writes that “Get it to me by 4:00 P.M.” e-mail, she is relying on the autocratic authority and the threat of punitive reprisal characteristic of blind obedience cultures to coerce results.

There are no hard walls between these four basic cultures; most groups organize themselves in a progressive and evolutionary state embracing elements of all four. They require some of the coercion of blind obedience (fireable offenses, for instance); some rules and acquiescence to them (but not the stupid ones); maybe a skosh of anarchy now and again to stir the pot; and some measure of self-governance. Larger groups may have a number of different, related, cultures operating separately within a single organization. A corporate board might have a culture distinct from the management team, which in turn oversees smaller teams with unique characteristics. GE/Durham represents a distinct unit within the large panoply that is GE, as different from its parent as MTV Networks is from other units of Viacom.

Culture can seem an ephemeral thing, one of those soft things that are so difficult to get a grasp on sometimes. Now that we have an overview of the essential

types

of culture that dominate business, let’s try to break it down further to understand the various

dimensions

of culture, the HOWS at work whenever a group forms for a common purpose. Let us explore ways to make something “soft” into something “hard” that we can do something about.

FIVE HOWS OF CULTURE

Culture occurs at the synapses where people interact. Synapses, as we know, are capable of receiving signals from many different sources at once, as a diamond can receive light from many angles and refract it in many directions. So let us imagine the processes of culture entering these synapses as light enters the facets of a diamond. The nature and character of the stone—thus, the culture—determine which light will get through, and in what direction it will travel. Though many things come to bear upon how culture grows and operates, some forces and structures are more influential than others.

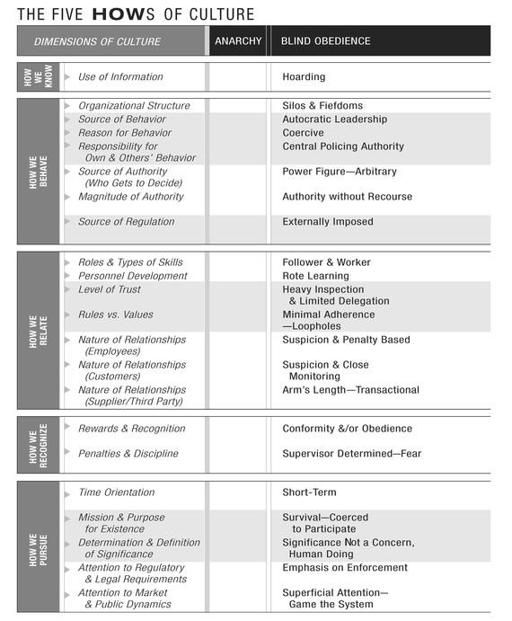

Figure 10.2

identifies 22 of what I think of as the most influential dimensions of culture, the facets through which human energy flows. Each dimension is defined by the way it manifests itself within the three types of cultures we are most concerned about. In order to better survey these dimensions, I have grouped them on a table into five HOWS: How We Know, How We Behave, How We Relate, How We Recognize, and How We Pursue (see

Figure 10.2

). The table provides the defining characteristics of each dimension for each of the three cultures we have discussed (the fourth, anarchy, I have inserted as a placeholder to remind you where it lives in the spectrum of culture, but left blank because it rarely relates to our lives today).

FIGURE 10.2

The Dimensions of Culture

How We Know

The first thing that distinguishes the nature of a culture is how it creates, communicates, and uses information. This single factor is so central and influential to our HOWs that it warrants a group by itself.

• Cultures of blind obedience hoard information in the hands of the elite few. Workers are primarily task-oriented. Bosses issue decrees from above with no explanation, and nothing strategic can be gained from letting others in on your secrets.

• As organizations and groups gain in complexity, informed acquiescence cultures require ways to transmit information in an efficient and orderly fashion. These companies go to extraordinary lengths to share necessary information—group members are well trained and can readily access the rules of conduct, for instance—but management still tightly controls other information and releases it on a need-to-know basis. The old maxim, “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing,” lurks just below the surface of all operational decisions.

• Self-governing cultures, by contrast, require conditions of transparency to thrive. If individuals, inspired by the core values of the group, are to be truly trusted to self-govern then they must have free and unfettered access to the information they need to make sound and reasonable judgments. At Nordstrom, for example, new employees receive a very simple statement that tells them almost everything they need to know about the company’s culture. First, it states Nordstrom’s fundamental commitment, “To provide outstanding customer service.” Then it lists the Nordstrom rules: “Use good judgment. We trust one another’s integrity and ability. Our only rule: Use good judgment in all situations.”

6

Perhaps no finer statement of self-governance exists today. But the key to the Nordstrom culture lies in the next statement, the last new employees receive: “Please feel free to ask your department manager, store manager, or division general manager any question at any time.” Deeply imbedded within the self-governing culture of Nordstrom is the idea that all information is accessible to everyone, regardless of seniority or status.

How We Behave

There are three basic ways that people can compel action in others: (1) They can

coerce

them, bullying, threatening, or cajoling them to do something against their will; (2) they can

motivate

them, using promises of reward or fear and threats of repercussion to get them to willingly agree that the desired action is in their best interest; or (3) they can

inspire

them, connect with them in a way that the desired action become a common goal. The second HOW of culture broadly encompasses the source and reason for personal or group behavior. Why do people do what they do? What keeps them from doing A rather than B?

• In blind obedience cultures, people obey. Autocratic leaders keep people in line by coercing them to comply. “Wear blue pants or you’ll be fired” is a clear indicator of a coercive relationship between leaders and followers. If you imagine a spectrum between internal and external control of behavior, blind obedience falls furthest toward the latter. The source of authority (i.e., who gets to decide things) falls to a power figure who can make unilateral decisions and wield that authority without recourse over those below them. To accommodate this sort of power structure, blind obedience cultures tend to have extremely vertical management structures, with authority concentrated in the hands of the few. Each boss rules his or her domain like an independent silo and fiefdom. The boss keeps everyone in line, decides what’s right and wrong, and provides clear marching orders.

If this sounds like the Army, you would not be far from wrong. Modern military cultures, which grew out of the experience of World War I, made blind obedience culture into a high art, and with great success. Unquestioning submission to central authority, they believed, built the floors of certainty, predictability, and unit cohesion necessary for soldiers to lay down their lives for one another. Though it may not sound like the most appealing culture in which to work, you might be surprised to learn that the movie business grew up in the same model. The fledgling motion picture industry took off just after the First World War. Returning veterans, looking for new opportunity, flocked to the West Coast to take up crew positions in this fast-growing new field. Film crews, like armies, are large mobile units that must move people and machinery from location to location in response to every changing demand. It made perfect sense for these new crew people to organize in the way they knew the best. Thus each department—sound, camera, lighting, sets, production, and so on—created its own autonomous fiefdom, with a rigid command-and-control structure. Though much more highly evolved, film crews today operate in much the same way around the world.

• Unlike blind obedience cultures, in which everyone defers to the boss, in informed acquiescence cultures everyone defers to the rules. Rules try to present an objective and fair guide for all behavior. These cultures tend to create organizational hierarchies based on expertise and function, promoting the most qualified to management roles where they manage by top-down decision making. Managers try to act consistently (and rationally) within the rules. The responsibility for monitoring fealty to the rules falls to a discrete organizational unit, often legal counsel or compliance officers, charged with training and monitoring compliance. Informed acquiescence relies on a reward and punishment structure to motivate people, and people follow because they see compliance to be in their own best interest. This central self-interest factor places informed acquiescence cultures in the center of the behavioral spectrum between internal and external control. People acquiesce to what is asked of them because they are primarily motivated by personal success, and they see doing what has been asked as a high-value step toward that goal. Leaders and managers in these cultures use carrots-and-sticks methods to motivate desired behavior.