How (17 page)

Authors: Dov Seidman

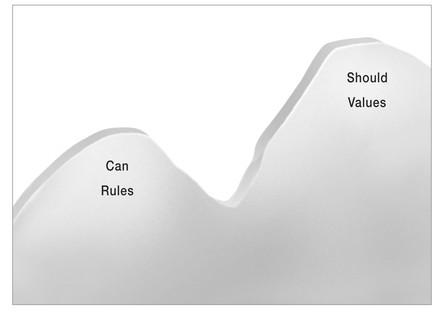

Thinking in the language of

can

versus

can’t

predisposes you to perceive challenges in a certain way and respond within narrow avenues. Thinking in and speaking the language of values—the language of

should

and

shouldn’t

instead of the language of

can

and

can’t

—opens up a wide spectrum of possible thought, a spectrum that encompasses the full colors of human behavior as opposed to the black-and-white responses of rules. This spectrum can lead to truly creative and innovative solutions to challenges.

UNLOCKING

SHOULD

I offer the legal challenges faced by Jenapharm and UMHS here because they paint a fairly black-and-white picture of the difference between thinking in

can

and thinking in

should

. Being presented with a lawsuit is usually far more serious than our daily confrontations with rules and regulations; however, our responses are in many ways identical in nature. We go through each day avoiding or complying with as much nimble grace as we can. The boss compliments you for a task you know was done by a junior associate on your team. Do you stop her and give the credit where the credit is due? You certainly

can

say nothing and let the moment pass unmentioned. There is no

rule

that requires you to credit a junior colleague; in fact, the unwritten rules of business permit you to take credit for the accomplishments of those who report to you. So you let the moment pass. This is rule-based thinking in its most insidious form.

I would guess that most people think that taking unearned credit is not right, even if you didn’t solicit it. It’s not something one

should

do, nor a value we agree with. And yet I would also hazard to guess that, if you think hard enough, you can think of a similar moment in which, either because of the absence of a specific rule or the presence of an ambiguous one, you let your actions be guided by your relation to a rule and not by what, in reflection, you

should

have done to be consistent with your values. Transcending the rules-trapped language of

can

and embracing the values-inspired language of

should

illuminates the pathways to truly innovative solutions like those of UMHS, as well as simpler choices like sharing the credit. UMHS achieved dramatically lower litigation costs; you, by sharing credit, earn the loyalty and increased dedication of a junior associate who, the next time your team needs an extra measure of effort to accomplish its goal, happily steps up and puts in the weekend hours necessary to get you there. To thrive in a world of HOW, you must balance your muscles of casual avoidance—as strong and developed as they are—with the ability to think in the language of values, in terms of

should

.

There is little in rules that inspires; by definition, you comply with them. All it takes to honor a rule is to do what it says, and nothing more. Rules breed a culture of acquiescence in which everyone comes to terms with them and finds a way to live within them or a way to circumvent them—in other words, to live in their positive or negative space. While giving someone the advice to “break all the rules” is terrible counsel, giving them the opposite age-old counsel to “just play by the rules” is now not that much better advice. It consigns them to a life of external servitude and a compliant mind-set. Thinking in the language of values frees you from the tyranny of rules and from the illusion of freedom you have when in their negative space.

To be capable of making Waves, you need an organizing principle more inspirational and compelling than rules. You can’t start a Wave by making a rule that Waves will happen every Tuesday after lunch. And if you could, what kind of a Wave would it be? Thinking and communicating in the language of

should

—values-based language—by its very nature inspires. The landscape of values is vast and unbounded, and creates a genuinely free space of creativity in which you can see new ways of accomplishing your goals. Values matter to us, and they matter to others, so they fill the synapses between us and others with greater meaning. Values provide floors plus propulsion because we think they are important, and because we tend to spend our energy on what matters most to us.

Justice

.

Truth

.

Honesty

.

Integrity

. Values have texture.

Fairness

.

Humility

.

Service to others

. The language of values inspires us because values are aspirational in nature. They propel us to higher ground. We don’t believe in rules but we all hold a belief in our values. They speak to the core of what makes us human. Values do double duty; they inspire us to do

more than

while simultaneously preventing us from doing

less than

. To betray them is to betray ourselves. They create natural floors without creating inadvertent ceilings.

We all have a core set of values, formed over time either by the influence of others—parents, teachers, mentors, friends—or learned through life experience. Unlike rules, which act as proxies for the things we care about—like a voting age approximates maturity and civic-mindedness—values are not a mechanism or device that approximates what is important or mediates between us and what is important; they connect us to it directly. Values play to our strengths as humans. Similarly, thinking of what we do in values terms imbues it with greater meaning. If two masons are paid equally for their day’s labor, which one walks away the richer, the one who was hired and managed as a bricklayer or the one enlisted and enfranchised as a cathedral builder?

There are myraid reasons why it is important now, more than ever before, to rethink our relationship to rules. First, twenty-first-century business craves creativity and innovation over almost all else, and freeing yourself from the constraints of rules-based thought unleashes new pathways of exploration and possibility. More important, in a transparent world we are judged as much by the process of HOW we solve problems as by the results we achieve. In a world where we have any number of competitors or potential competitors, HOW we do what we do is the thing that increasingly differentiates us from the other guy. There is hardly a business that doesn’t suffer from “the grocery store syndrome.” We can choose from any number of grocery stores, each one offering competitive prices. After price, the choice of where to shop usually boils down to customer experience, the quality of the human interaction that occurs there. We want to shop where it is pleasant, where the goods are easily seen and obtained, and where the employees respond positively to us. To provide this sort of experience in everything you do, to discover ways to outbehave the competition, you need to think in ways that inspire your best achievement, to think in the language of

should

.

RISK AND REWARD

Thinking in the language of values unlocks powerful possibilities for growth and action, but at first blush it can seem dangerous to some. For the senior management of companies, shifting the way you lead and govern people from rules-based to values-based thinking sometimes brings the fear of losing control. Governing by rules shifts less power down the hierarchy, allowing those at the top to believe they can easily control the actions of those below them. This is a habit of mind left over from the days of fortress capitalism and feudalism. Leading from values, on the other hand, decentralizes power and shifts the responsibility for decision making into the hands of individuals at all levels. Values are not black-and-white or quantitative. Values are like trust; they empower others to honor or betray you. They open up avenues of possibility and leave room for interpretation.

Surprisingly, though, values-based leadership has a tremendous upside. As business units spread around the world and more and more interactions take place among equals in the organization, top-down governance strategies become less effective. The trend of twenty-first-century business to become more horizontal, in fact, creates fertile conditions for leadership strategies that thrive in decentralized environments. While this shift of power may at first seem to make values-based thinking dangerous for businesses of all sizes, it ultimately makes them more powerful. The new conditions of the world of HOW call out for exactly this sort of approach. Values-based thinking truly frees the individual to act in the interests of the organization.

When Harry C. Stonecipher, the president and CEO of Boeing, was asked by Boeing’s board to resign after having an extramarital affair with another employee, for example, the company could have responded by amending its code of conduct to prohibit or restrict certain kinds of relationships between employees. Instead, Boeing did something far more interesting: It enshrined and enforced a value. Lead director and former non-executive chairman of Boeing, Lewis Platt, said, “The board concluded that the facts reflected poorly on Harry’s judgment and would impair his ability to lead the company . . . the CEO must set the standard for unimpeachable professional and personal behavior, and the board determined that this was the right and necessary decision under the circumstances. We have fought hard to restore our reputation. Everyone should know that if we see any improper activities, we will take decisive action.”

20

Boeing sent the message that employee behavior does not answer to a set of rules, but to a much more powerful standard:

repute

. In a stroke, Boeing employees understood that part of their job involved bringing the company positive repute, and that integrity was so central to what Boeing is that it could cost even the highest executives their jobs. By celebrating a value rather than instituting a rule, Boeing gains much tighter alignment with its workforce. Every employee must internalize this value, wrestle with it on an ongoing and individual basis—deep in the Valley of C—and thereby develop a much more active relationship to the company’s desires and a tighter alignment with its goals. The value, while seemingly less direct than a rule, achieves a greater result.

Even within a lower-skilled, service-oriented workforce like fast-food giant McDonald’s, values provide a means of tighter integration with company goals. “The whole experience at McDonald’s boils down to the moment of truth at the front counter or drive-through, that 30 seconds of interaction,” CEO Jim Skinner told me when we met at the company’s Oak Brook, Illinois, headquarters. Skinner built his career on knowing that moment. He began his career with McDonald’s in 1971 as a restaurant manager trainee in Carpentersville, Illinois. “The development of that relationship between our people and the customer is probably the hardest thing that we do. With hundreds of thousands of employees serving more than 50 million customers a day across 119 countries, common values are essential. They are efficient. They form the link among all our moving parts, allowing everyone who serves the McDonald’s brand to understand what it means to be successful at that moment of truth with a customer.”

21

FROM

CAN

TO

SHOULD

Can

versus

can’t

thinking substitutes for genuine time spent considering the HOWs of a given situation (HOW can I best delight my client? HOW can I bring the company greater repute? HOW can I make this meeting more successful?) and fosters a passive relationship to interaction with others (WHAT does the manual say to do? WHAT is my job description? WHAT is on the agenda?). In this mode of thought, you believe you can do what you want as long as you comply with the contract or the code. When you think in the language of values, however, you must actively engage each situation. Values propel action toward others. This creates an energy focused on

HOW

you do WHAT you do, and that energy becomes a propeller, driving a Wave of action toward others. In an information economy, where more power lies in the network than in the individual, outwardly focused energy makes sense as a propeller of success.

From

can

to

should

. From rules to values. These fundamental shifts in language exert a profound effect on the way you think, orient your energies, make decisions, and, therefore, achieve. New language may seem awkward at first, like learning to communicate in something other than your native tongue. But people who learn a second language often develop better grammar than native speakers, because they do so as a conscious act of will. Understanding the interplay of rules and values, and freeing yourself from the tyranny of

can

versus

can’t

are essential steps toward mastering the grammar of the new world of HOW.

CHAPTER

6

Keeping Your Head in the Game