Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet (28 page)

Read Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet Online

Authors: Frances Moore Lappé; Anna Lappé

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Political Science, #Vegetarian, #Nature, #Healthy Living, #General, #Globalization - Social Aspects, #Capitalism - Social Aspects, #Vegetarian Cookery, #Philosophy, #Business & Economics, #Globalization, #Cooking, #Social Aspects, #Ecology, #Capitalism, #Environmental Ethics, #Economics, #Diets, #Ethics & Moral Philosophy

Part I

Tips for Making Meals Without Meat

1.

What Is a Meal Without Meat?

W

HEN AS CHILDREN

we asked our mothers, “What’s for supper, Mom?” the shorthand answer always came back “Pork chops” … “Chicken” … “Meat loaf.” The meat course defined the meal.

These menus, which many of us take for granted, are inherited from our physically active forebears. But in our mechanized society we often need many less calories each day than did our great-grandparents, who worked the fields, carried water, and washed by hand. This fact has become well known, if not well heeded. The trouble is that it is virtually impossible to avoid consuming too many calories per meal as long as you define a meal as meat-vegetable-starch-salad-bread-and-dessert. It just can’t add up any other way than

too much

.

But once meat is no longer the center of the menu, then the whole pattern of habit falls apart. Anything goes. We are free to respond to our own appetites in planning menus. In my family what seems most natural is a one-dish meal into which we put our care and imagination, accompanied by one simple side dish such as salad, good hearty bread, or a steamed vegetable. Therefore, the majority of the recipes in the book, and all those in the first section of the recipes, are not merely main-dish ideas but really “meal-dish” ideas—meals in themselves with (if you choose) the addition of a simple salad, etc.

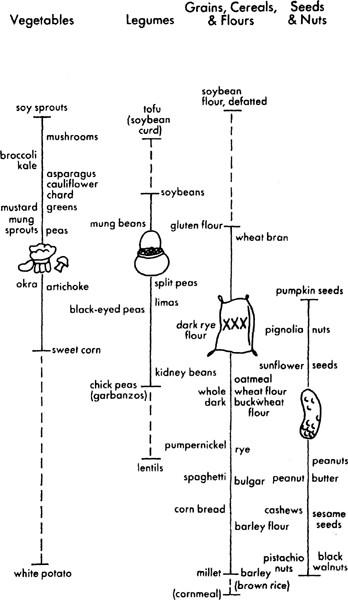

In focusing on how to get protein without meat in the first two editions of this book, I fear I reinforced a preoccupation with protein. In this edition I’ve tried to correct for that, emphasizing how much easier it is than most of us thought to get the protein we need. (My “Hypothetical Diets” in

Figures 10

and

11

make this point.) Once we lower our estimation of the amount of protein our bodies need, and realize how many foods provide protein—even those, such as green vegetables, that we’ve never thought of as protein sources—we gain much more flexibility in meal planning. We no longer have to pack scads of protein into a dish filled with cheese and eggs. We can use more vegetables, grains, and fruit. We achieve greater variety and lighter meals.

Letting go of the meat-starch-vegetable formula and experimenting with new foods was, for me, satisfying in yet another way. Because there is no Betty Crocker of plant foods telling me what a dish

should

be like, I became more experimental. I recall the first nonmeat dinner party I ever gave, for which I made a walnut-cheddar loaf. Never too confident about my cooking, I was comforted by the thought that at least no one would be comparing my dish with Julia Child’s version (who else ever tasted walnut-cheddar loaf?). After you become comfortable with the ingredients, you will become a creator, taking foods that are in season and on hand and creating your own favorites.

But let me offer one important caveat that I also included in the first edition of this book: don’t expect yourself to change overnight. Start with one new menu a week, or one new ingredient, until you gradually build up a repertoire of dishes you enjoy. Suddenly changing lifelong habits of any kind on the basis of new understanding does not strike me as very realistic or even desirable, however great the revelation. At least, this is not the way it has worked for me.

Why Meatless?

In Book One I explained the difference between the diet I advocate and “vegetarianism.” I said that what I advocate is a return to the traditional diet on which our bodies evolved—a plant-centered diet in which animal foods play a supplemental role. But the recipes in my book have always been meatless. Isn’t this a contradiction? If I’m not advocating a totally meatless diet, then why don’t the recipes contain meat? Well, here’s where the personal and the intellectual parts of me come together. Intellectually, I believe that meat has a role to play in human nutrition, since livestock can convert nonedible substances into high-grade protein for people—and in some parts of the world, where cropland is scarce but grazing land plentiful, they seem to play an essential role. Personally, I don’t like to cook with meat and I feel much better when I don’t eat it. However, my personal preference for a basically meatless diet should not deter others from using this book. If you do not want to eliminate meat completely, you can still use almost any of the recipes, simply adding small quantities of meat. Eating meat occasionally and adding small quantities to plant-centered meals does not violate the themes of this book.

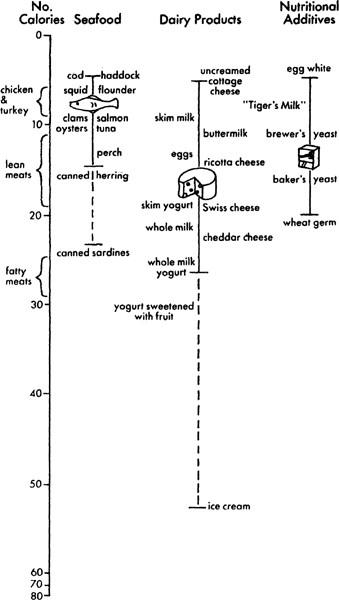

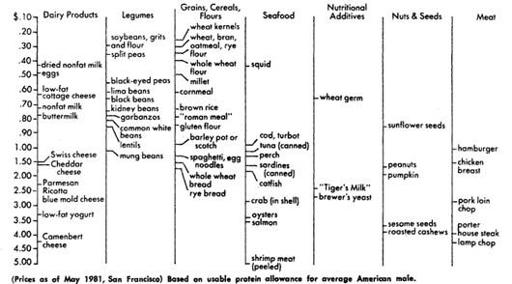

The Calorie and Dollar Costs of Protein

Other questions people often have about plant-centered versus meat-centered diets concern the dollar cost differences and the calorie “cost” differences, so here are two charts that, at a glance, give you a sense of how a variety of foods rank.

Figure 17

tells which foods give you the most protein for the fewest calories.

Figure 18

tells you which are the cheapest protein sources.

Figure 17. Calorie “Cost” Per Gram of Usable Protein

Figure 18. Cost of Getting One Day’s Recommended Protein Allowance (40 grams)

2.

“But It Takes Too Much Time …”

…

IS ONE OF

the most common reactions to the suggestion of cooking with whole foods. I used to resist making even so-called quick breads from scratch. How could they be as quick as a ready-made mix? But when I began to want dishes that demanded I start from scratch, I decided to test myself. How much more time did it actually take to make my corn bread recipe than to use a commercial corn bread mix? Hardly any more time at all! Both required that I get out bowls and utensils, mix the batter, oil the baking pan, pour in the batter, put it in the oven, clean the mixing utensils and then the baking pan. The only difference was that with my recipe I had to combine a few more ingredients—a really minor part of the whole operation.

But people continue to tell me that they can’t wait for the long cooking time necessary when using whole foods, can’t take time to chop fresh vegetables and hand-make exotic ethnic dishes. Still, while the actual time my stove is in use may be longer than it takes to fry a hamburger, I am sure that I do not spend any more of my time on food than they do. So what is the secret? Part of the secret is:

1. knowing what to have on hand for easy meals;

2. taking advantage of “intentional leftovers”;

3. changing where you shop;

4. a handy kitchen layout and time-saving utensils.

What to Have on Hand

There are probably certain foods that you always have, that you shop for automatically because you know that with these basic ingredients you can always produce a good meal. As you begin to change your eating habits, your buying and stocking habits will change too. To help you, I made a list of the items that I am virtually never without. Many of these foods are probably in your kitchen right now, but perhaps it never occurred to you that you could build a meal with many of them. Of course, in each of these categories there are many, many more possibilities, but with these items you could make

any

of the recipes in this book. (You might have to substitute a little, but that is part of the fun!)

Again, I am not suggesting that you go out and buy a whole lot of new ingredients all at once. If you have a friend who uses whole grains, legumes, and seeds, ask if you might just have some samples to get you started. (That’s how I got started, with the help of a dear friend, Ellen Ewald.) One of the many advantages to shopping at a food co-op is that you can buy many grains, flours, pastas, etc., loose from bins, so you can buy very small quantities.

Another way to begin is to find a friend who would also like to experiment. Together you might buy one-pound quantities of a few new things, split them, then compare experiences and reactions to your new menus. This way you will not be making such a big initial investment that you will feel it

has

to “work” all at once. Or, if you are on your own, just find one recipe that looks good to you. Buy any ingredient you don’t already have, then try discovering all the other possibilities for it. You’ll be amazed at the variety that is possible when cooking with plant foods.

Here are my basic pantry items for easy meals, with some tips on how I use them. (For basic cooking instructions, see

Appendix C

.)

D

AIRY

P

RODUCTS

Nonfat dry milk

. In hot cereal, baked goods, soups, blender drinks, white sauces.

Low-fat cottage cheese or ricotta cheese

. The basis of sauces, salad dressings, casseroles, pancake filling, pie filling, or simply a delicious spread on bread.

Low-fat yogurt or buttermilk

. A dressing for fruit salad, in blender fruit drinks, cold summer blender soups, and sauces (especially with curries). You can use buttermilk in place of yogurt wherever you don’t need yogurt’s thickness. It’s much cheaper, too.

Soy Foods

Tofu

(soybean curd) has a mild flavor and the consistency of firm custard. It readily absorbs the flavors with which it is cooked. Uncooked, tofu can be blended for salad dressings and sauces. Lightly sautéed with vegetables and seasonings, it becomes a main dish. Actually, tofu can be used in almost any kind of dish, as you’ll see in the recipes that follow. Tofu and soy milk also can be used in place of milk in virtually any recipe.

Tempeh

(a fermented soy curd) and

miso

(a fermented soy paste) are also favorites of growing numbers of Westerners. They lend themselves to many different types of dishes. The best source of information about soy foods, including hundreds of delicious recipes, are the books of Bill and Akiko Shurtleff,

The Book of Tofu, The Book of Miso

, and

The Book of Tempeh

(Ballantine Books).

Q

UICK

-C

OOKING

G

RAIN

P

RODUCTS

Bulgur

(partially cooked, i.e., parboiled wheat, usually cracked). For breakfast cereal, dinner grain, soup thickener, cold salad with vegetables. (Couscous is similar but more refined, and usually more expensive.) Bulgur’s nutty flavor is enhanced by sautéing before steaming.

Flours

—whole wheat, soy, corn. Endless possibilities!

N

UTS AND

S

EEDS

Sunflower and ground sesame seeds

(nutritionists have advised that sesame seeds should be ground for digestibility; this can be easily done in the blender or with a mortar and pestle). Used in baked goods, salads, as a toasted topping, in casseroles, stuffing, granola, with peanuts for snacking. Toasting lightly brings out the flavor.

Peanuts and peanut butter

. In bean croquettes, casseroles, salads, cookies, candy, vegetable sauce for pasta, curries.

Q

UICK

-C

OOKING

D

RY

L

EGUMES

Split peas

(green or yellow). Soups, curries, sauces, with rice, in rice patties, loaves.

Lentils

. Same uses.

Soy grits

(partially cooked, cracked soybeans; also called

soy granules)

. In hot cereals, baked goods, in small amounts with other grains, in spaghetti sauce or bean chili, soups—or in just about anything for extra protein. Soy grits have a very mild taste and absorb the flavor of whatever they are cooked with.

O

IL AND

M

ARGARINE

You’ll notice that in this edition I have replaced butter in the recipes with margarine or oil. For my reasoning, I refer you back to the “America’s Experimental Diet” chapter in which I discuss the importance of reducing our intake of cholesterol. I recommend that you use natural magarine, which does not contain chemical additives. The best vegetable oils for your health are polyunsaturated. They include safflower, sunflower, corn, and soybean oils.

F

RESH

F

OODS

These are fresh foods that keep well. With these three vegetables you can, as a friend put it, always create a meal out of nothing.

Carrots

. In carrot and onion soup, bread, grain dishes, salad, curries.

Onions

. French onion soup, in casseroles, curries.

Potatoes

. In soups, salads, casseroles, pancakes.

C

ANNED

F

OODS

Kidney and garbanzo beans

. In stews, chili, tacos, puréed for sandwich fillings, curries. (I use canned beans only when I am really rushed and have used up my freezer store of leftover cooked beans.)

Tomatoes

. In soups, casseroles.

Spaghetti sauce

. In pasta dishes, as topping for bean croquettes, eggplant platters.

Tuna fish

. In casseroles, sandwiches, salads, rice fritters.

Minced clams

. In chowder, spaghetti sauce, dips, spreads, fritters.

Beets

. Add beautiful color and interest to vegetable, tuna, lettuce, or spinach salads.

Corn

. In casseroles, fritters, soups, stews, pancakes.

F

REEZER

F

OODS

Leftover beans

. Always cook at least twice what the recipe calls for and store the rest for instant meals.

Middle Eastern flatbread (pita) and tortillas

. Use for authentic foreign dishes and for instant sandwiches with all types of fillings. (Cheese melted on tortillas makes a quick and delicious snack—and kids love it.)

Frozen peas

. Add color, taste, and nutrition to soups, stew, salads, etc.

S

EASONINGS

(“S

EASONED

S

TOCK

”)

Powdered vegetable seasoning

. Use in just about anything. Look around and you can find vegetable seasonings that are made from natural ingredients, without preservatives or salt. Use with water whenever the recipe calls for Seasoned Stock, or sprinkle on whenever you think extra flavor might be needed.

You can make your own seasoning to sprinkle on a little extra flavor. Here’s a suggestion from Alice Green of San Francisco: take 3 sheets of nori (pressed seaweed, available in Asian or natural foods stores) and toast one side of each sheet over a gas burner (to enhance the flavor). Then roast ¼ cup of sesame seeds in a dry skillet until golden. Crumble the nori and combine with seeds in a small jar with a tight lid. Shake well. (I would add that you might want to put the seeds in a blender or grind them to release flavor and aid their digestibility.) This is good on all grain and vegetable dishes, Alice says.

Herbs

. You can substitute fresh herbs for dried herbs, or vice versa, by using the following rule of thumb in the recipes that follow: for every teaspoon of dried herbs, use roughly one tablespoon of fresh. But be careful to taste as you go: herbs vary greatly in strength.

Unless otherwise indicated, the recipes call for dried herbs

.

Intentional Leftovers

Prepared foods are popular because it

is

nice, when you are exhausted after a long day, to just take a delicious dish out of the refrigerator, heat, and serve.

But why not make your own TV dinners? Again, it is a question of habit. If we get into the habit of preparing more than we will eat in one meal and freezing the rest (in containers that can go right into the oven, if appropriate), then we can have our favorite foods there ready for us when we are too tired to cook.

Cook extra beans for the freezer—to be added later to soups, casseroles, or salads. Also, cooked grain keeps well for about four days in the refrigerator. My children like to add milk or buttermilk and a touch of brown sugar (and sometimes some nuts) to leftover brown rice or bulgur for instant cereal. Cooked potatoes also keep well in the refrigerator for at least that long. They can become a quick salad (delicious with other vegetables and a vinaigrette dressing), hash browns, or dozens of other delicious potato dishes.

Shopping

One of the most effective ways to change how you eat is to change how you shop. In a giant supermarket that offers (or should I say bombards us with) 15,000 items, finding healthy foods seems like a struggle. If we shop in a smaller, whole foods cooperative store, we are surrounded by foods that not only tempt our palates but are good for us. A second argument for shifting to a whole foods store is time. Even though I measure out the quantities myself, it takes me less time to shop at the Noe Valley Community Store than at the supermarket. Maybe this is because I know exactly where everything is and I don’t have to walk down long aisles of items I would never buy. In addition, shopping in my community whole foods store probably seems even quicker than it is, because I enjoy it. A supermarket trip seems like an ordeal to endure. A trip to the community store is a totally different experience. Everyone there seems to want to be there, including the people who work there.

Cooking with grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds also means that in one shopping trip you can buy enough to last a few months.

Kitchen Shortcuts

K

EEPING

I

T

A

LL

W

ITHIN

R

EACH

Preparation time is not just how long something takes to cook; it’s getting the ingredients to the cooking stage, too. That’s why the organization of your kitchen is all-important.

All that wasted space at the back of your kitchen counters could be a beautiful and handy storage area for your whole foods. All you need are large glass jars with tight-fitting lids. Giant peanut butter or pickle jars are good. Flours, seeds, beans, lentils, even pasta and milk powder can be kept within easy reach. The variety of color and texture will add an attractive touch to your kitchen, too. Also, being able to see all the ingredients can be a spur to the imagination.

I

inevitably end up tossing in a little of something that

I

had not planned to, just because

I

see it there on the counter.

Measuring utensils can also be in easy reach of your basic ingredients. Get measuring cups with long handles with holes in them for hanging. Hang them on hooks from a cupboard over your storage jars, if possible. Measuring spoons can also be hung on a hook. Just think how much time you might save if you never again had to fumble through the utensil drawer for measuring cups or spoons! As soon as I wash mine I hang them on their hooks. That way I never have to dry them and always know where they are.