Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet (26 page)

Read Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet Online

Authors: Frances Moore Lappé; Anna Lappé

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Political Science, #Vegetarian, #Nature, #Healthy Living, #General, #Globalization - Social Aspects, #Capitalism - Social Aspects, #Vegetarian Cookery, #Philosophy, #Business & Economics, #Globalization, #Cooking, #Social Aspects, #Ecology, #Capitalism, #Environmental Ethics, #Economics, #Diets, #Ethics & Moral Philosophy

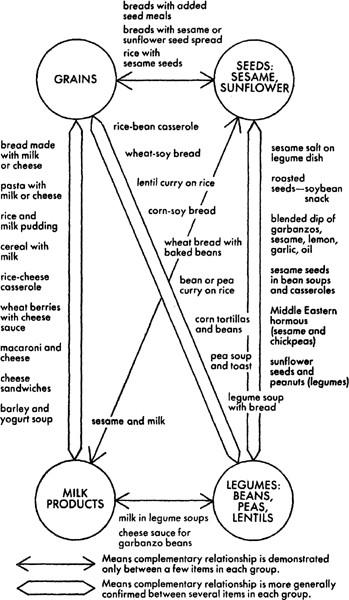

Figure 15. Demonstrating Protein Complementarity

Eating wheat and beans together, for example, can increase by about 33 percent the protein actually usable by your body.

Figure 15

will help you see why. It shows the four essential amino acids most often deficient in plant protein. On each side, where beans and wheat are shown separately, we see large gaps in amino acid content as compared to egg protein. But if we put the two together, these gaps are closed.

Figure 16

, “Summary of Complementary Protein Relationships,” illustrates the basic combinations of foods whose proteins complement each other. The dishes listed are meant to be suggestive of the almost endless possibilities using each combination. (Complete protein tables are in

Appendix E

.)

The Complementarity Debate

Since the first edition of

Diet for a Small Planet

, many have pointed out that it is not really necessary to eat complementary proteins

in the same meal

, as I implied. They are right, technically. But experimental evidence suggests that protein assembly will slow down after several hours if all of the amino acids are not present. “If a diet lacks only one essential amino acid, which is provided several hours later, efficient use of all amino acids falls,” says a National Academy of Sciences report.

2

So it would seem that unless we eat more than three meals a day, the only way to

ensure

protein complementarity is to eat complementary proteins in the same meal.

In 1972, E. S. Nasset reported evidence of an “amino acid pool” that could make up for any deficiencies in the amino acid patterns of the food we eat. Nasset’s work has been cited by many to suggest that eating complementary proteins may be irrelevant. But most nutritionists disagree with Nasset. His amino acid pool theory “has been questioned by a number of workers and the results presented so far do not support Nasset’s theory,” reports a 1978 study.

3

This view is confirmed by MIT’s Nevin Scrimshaw, a member of the group that sets the UN’s recommended protein allowances: “The Nasset Hypothesis is fallacious in that it applies only to the amino pattern in the intestine and not the overall amino acid turnover of the whole body.” Scrimshaw adds, “It

is

necessary to eat complementary protein within three to four hours.”

4

Figure 16. Summary of Complementary Protein Relationships

In sum, then, here is what I have learned about protein in the last 10 years:

• To obtain more usable protein we don’t have to eat complementary proteins

in the same meal

, if we have frequent meals. But doing so seems to be convenient and easy, since so many dishes combine complementary proteins anyway.

• For effective protein use, however, we do need to eat complementary proteins within a few hours of each other.

• For most people, even those eating strictly a plant food diet, attention to complementary proteins is not necessary as long as the diet is healthy otherwise. Exceptions include pregnant and breast-feeding women; they must increase their protein more than their calories.

•

No one

should accept blindly the recommended protein allowances. Variations in protein need among individuals are so great that we must pay close attention to our need for more or less protein, observing both our overall sense of well-being and such danger signs as poor healing and unhealthy hair or nails.

• Presently available NPU ratings, such as those used in

Appendix E

to show the percentage of usable protein in foods, probably overestimate available protein. But since most people eat at levels above the recommended allowances, even without meat, this is generally no problem.

Part IV

Lessons for the Long Haul

1.

What Can We Do?

T

O BE PART

of building a more democratic society, one in which our economic structures are accountable to people’s needs, what can we do? Since we can’t take on the whole system at once, where can we start? How can we find others to work with, people who will not only help us accomplish our goals but also help us change ourselves?

I’ve found that food issues have a special ability to open doors. Everyone has an opinion about food, because everybody has to eat! But, as I have said, I’m not suggesting that everyone should become a food activist. Our society’s gravest problems have common roots, so we can work in many areas—toward better schooling or health care systems or toward safe energy policies—and we will affect all the others.

In a dozen years focused on food problems, traveling back and forth across the United States, I’ve met hundreds of other people working on everything from food co-ops in Michigan to investigating center-pivot irrigation in Nebraska to water rights in California. I consider all these people allies, and some have become close friends, even if we get to see each other only a few times a year.

But I always fear that people who have never been involved in work for social change believe that people already intensely engaged are somehow different from themselves. They assume: “Well, she must have

always

been self-motivated and had direction. I could never be that way.” In my experience, this perception is just not accurate, certainly not when I look at the progression in my life. One goal of this book and of the book

What Can We Do? Food and Hunger: How You Can Make A Difference

,

*

which Bill Valentine and I wrote in 1980, is to demystify the people already involved—to show that we all must undergo the same struggles. None of us is spared the uncertainties. It may look easier for the other person, but it probably isn’t. For

What Can We Do?

we interviewed two dozen food and hunger activists in the United States and Canada and tried to find out what makes them tick. How did they get involved? How do they see their work changing the food system? And what keeps them going? In this chapter I would like to share some of their responses as well as those from people around the country who wrote to me as I was preparing this edition.

Use What We Have

As I was working on the final draft of this chapter, the popular balladeer Harry Chapin died in an automobile accident. He was thirty-eight. I was deeply affected, because Harry’s life reflected many of the themes in this book—especially this chapter. Joe and I first met Harry in 1976, when

Food First

and our Institute were just being born. The year before, Harry and radio talk-show host Bill Ayres had founded World Hunger Year as a vehicle for their work against hunger.

What first struck us was Harry’s drive to learn. I guess we’d assumed that entertainers who got involved in “causes” were not too concerned about the facts; they were out to prove they had a heart, not just an ego. But Harry was different. We sent him the drafts of the

Food First

manuscript and we held informal seminars to discuss our findings. I felt that what appealed to Harry most was that ours is a message of hope.

While Harry’s fame came from his hits “Taxi” and “Cat’s in the Cradle,” his most fervent fans were those who had seen him in concert. In his concerts Harry broke all the “pop star” rules. He needed no gimmicks. It was just Harry—in simple street clothes, with no props. Harry sang ballads about the pathos of everyday life—and between songs told people of the tragedy of needless hunger—yet he left his audiences uplifted. How did he do it? By the force of his character, grounded in certain core beliefs. One he called the “nudge factor.” To him this meant the power of even a small minority to bring about enormous change—if that minority just cared enough. In Harry’s presence, you

had

to believe, for it seemed as though even a minority of one could do the impossible.

When someone like Harry Chapin is gone, we feel an enormous void. But we can use the lessons his life taught to take up the challenge of filling that void. Perhaps the most important lesson is to use what we have. He started with what he had—musical talent and incredible energy—and used them to open doors for millions of people. He was directly responsible for the birth of three antihunger organizations and, through these, several more. One spinoff was the New York City Food and Hunger Hotline, through which hungry people can get emergency help and support in coping with the government food programs. Harry also made major contributions to our Institute during the early years when we needed help most. In addition, Harry did benefit concerts for dozens of other causes. He gave away several million dollars.

Harry used his fame as a singer in other imaginative ways. For example, he was able to convince radio station managers in ten major cities all over the country to hold “world hunger radiothons”—24 hours of commercial-free air time, during which all the breaks were filled with information and insight about the causes of hunger. And the shows were not just “Harry’s shows.” His staff, led by Jeri Barr and Wray McKay, did the tiresome work of drawing in local spokespeople to tell about the problems and the struggles right in the local community. The goal: to ignite local activism.

Harry started with what he had and used it. That’s the challenge of his life to us.

The First Step Is the Hardest

From Harry Chapin, from the many, many people I have met in the last ten years, I learned that we must each begin from where we are. Each person’s interests, passions, abilities, age, and geographical location affect the actions one can—and wants to—take. In seeking a focus for action, many choose to look close to home, doing what they can right now, and then taking the next step as it comes.

Cathy Adrian of Santa Barbara, California, was working in a doughnut shop when she became interested in food problems ten years ago. “I began to see things in a different light,” she explains. “A spark had been set off inside me that has continued to get stronger.

“I started talking to my customers who were friends about nutrition and found myself talking people out of buying coffee and doughnuts,” she remembers. “It goes without saying that I felt out of place at the doughnut shop.” Today she works as a teacher’s aide for special-education preschoolers. At the food co-op where she shops, she has set up two bulletin boards because “I needed a way to effectively share information. I want to help people become more aware and, most importantly, become

active.”

Twelve years ago Joan Gussow was forty, at home with two children, and working two days a week on a book project she was less than enthusiastic about. When that work was completed, Joan said, “I kept asking myself,

‘Now

what are you going to do when you grow up?’ ” When she first thought of going back to school to study nutrition, the idea frightened her. “I realized that I had my last chemistry course in 1949!” Joan said. “But, being more honest with myself, I realized that my main reservation was nutrition’s dull

image

. (Let’s face it, nutrition is not one of the high-prestige fields.) But that’s a pretty crummy reason for not doing something you believe in … just because other people don’t think it’s important. I told myself, if

you

think it is important, make it important.”

Joan is now head of the Department of Nutrition and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University, a sought-after speaker, and author of

The Feeding Web: Issues in Nutritional Ecology

(Bull Publishing, 1978).

In retrospect Joan believes that the decision to go back to school to study nutrition was probably the first real decision in her whole life. “Yes, I responded to offers, and in other instances there seemed to be no choice, so I went through whatever door opened,” she says. “But in this case I made the decision because of what I thought was important. And I’ve never regretted it.”

Bob Pickford, who works for the Federation of Ohio River Co-ops in Columbus, says he “became involved in co-op work as a consumer at a food cooperative, looking for higher-quality food than was available in the supermarket, or a little less expensive food.

“I spent more time at the co-op, began to understand a little bit about what a food cooperative was, and started to work as a volunteer. Since then I’ve worked as a paid worker in several stores, and now as a paid employee in the warehouse.” The Federation operates a central warehouse and about 100 buying associations in Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana. It places a few cents’ tax on every product from the third world and uses that fund for educational projects and donations to groups addressing the roots of hunger.

“If you asked me 12 years ago, I wouldn’t have believed that I could be doing work on enforcing a law that would provide access to inexpensive, highly productive agricultural land for thousands of small family farmers,” explains Maia Sortor of National Land for People in Fresno, California. “I used to earn my living doing commercial art for products I could no longer stomach. And now I do graphics for the purpose of educating people about how they can get more control over their lives and stomachs.”

Marilyn Fedelchak, who farms 320 acres in Churdan, Iowa, works with the U. S. Farmers’ Organization, seeking a fair income for farmers. “When I married a farmer,” she says, “I looked forward to living in rural America. I thought I would be close to nature and be part of a community … I guess I got involved because I think there is still hope for the kind of rural America that I wanted to live in.”

Leah Margulies, a leader of the Nestlé infant-formula boycott at the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility in New York, recalls, “Ten years ago I was a housewife. I was pretty despairing about changing my life. I first got involved through the women’s movement, in a collective studying how multinational corporations are expanding their markets overseas. What I started to think about initially was the way women’s realities are formed by economics. I started to question whether or not the kind of people that are being created by the necessity of ever-expanding sales of consumer goods are really the kinds of people we in the women’s movement wanted to be!”

The Interfaith Center where Leah works coordinates efforts by church denominations and agencies to use their power as shareholders to raise questions of social justice within corporations. Every shareholder in a corporation has the right to introduce resolutions suggesting changes in corporate policy, and the Interfaith Center has used these resolutions to force discussion of bank loans to repressive governments, the portrayal of women and minorities on television, and unfair labor practices.

The Center works closely with INFACT, a national coalition of 450 local organizations trying to prevent the advertising of infant formula to third world mothers. (Once mothers get hooked on using formula, their breast milk dries up, but often third world mothers are too poor to buy as much formula as their babies need. They are forced to stretch it with water that is frequently unsanitary or with other nonnutritious substitutes. So millions of babies die who

might

have lived if their mothers had breast-fed them instead of believing the suggestion of Nestlé and other multinationals that bottle feeding is “modern” and better for babies.)

Ten years ago Michael Jacobson was getting his doctorate in biochemistry at MIT. He had no particular interest in food. “In 1970, I’m not even sure I’d ever heard of a ‘whole grain,’ ” says Michael. “I was spending all my life in the library and with test tubes. But I was dying to do something—anything—that would touch our immediate social problems. So I took a chance. I signed on as an intern with Ralph Nader. Since I had the science degree, my assignment was to look at the hazards of food additives. And out of that summer eventually came my first book,

Eaters’ Digest

(Doubleday, 1972).

Within a year, Michael and two other scientists had launched the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a Washington-based public interest group which now boasts 25,000 members. Its nutrition education materials are used by thousands of teachers around the country. And its public advocacy has helped alert the country to dangers of the new American diet I describe in

Part III

. The Center has taken on the food industry in fighting for accurate food labeling and against hazardous additives. It has exposed the shocking collusion among industry officials, government regulators, and “objective” academics.

Trapped by the pressure of exams and term papers, students often feel they just can’t get involved in the kind of social change work they most want to do. But students at the University of Oregon decided that what they

could

change was the nature of the courses on world hunger being taught right in their own university. Brad Oppermann and two classmates organized their own for-credit course, “World Hunger and You,” through the sociology department. “It’s been going for two years and now attracts 30 to 40 students,” writes Brad.

For Kathleen Cusick, the decision to stop eating meat was the first step which led her to work with Rural Resources, a Loveland, Ohio, group which has helped set up tailgate farmers’ markets in Cincinnati and a Citizen’s Alliance to fight a proposed sewer project in a nearby rural community.

“It began with the negative emotional responses I got from people even to that one personal decision not to eat meat,” she recalls. “The more I followed through on that decision, and discovered why I made it, the more I discovered that my decision to become involved in food work was something that very few people were doing.

“It was frightening because for a long time there was really no support,” she remembers. “This kind of decision—to be an organzier or activist—really has to be made with some community support. Otherwise it can turn you into a loner, and make you very ineffective and unhappy.”