Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet (13 page)

Read Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet Online

Authors: Frances Moore Lappé; Anna Lappé

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Political Science, #Vegetarian, #Nature, #Healthy Living, #General, #Globalization - Social Aspects, #Capitalism - Social Aspects, #Vegetarian Cookery, #Philosophy, #Business & Economics, #Globalization, #Cooking, #Social Aspects, #Ecology, #Capitalism, #Environmental Ethics, #Economics, #Diets, #Ethics & Moral Philosophy

*

World Hunger: Ten Myths

, by Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins, one of our Institute’s most popular publications, further explodes these myths. See our address on page 481.

*

I cannot overstress the importance of this decision. I commend to you Jerry Mander’s beautiful book

Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television

(Morrow Quill Paperbacks, 1977).

*

Aid as Obstacle: Twenty Questions about Our Foreign Aid and the Hungry

, co-authors Joseph Collins and David Kinley, Institute for Food and Development Policy.

*

To understand what has happened in Nicaragua since the fall of Somoza, see our Institute’s book,

What Difference Could a Revolution Make? Food and Farming in the New Nicaragua

, by Joseph Collins, 1982.

Part II Diet for a Small Planet

1.

One Less Hamburger?

I

REMEMBER RIDICULING

Hubert Humphrey’s comment that if we all just ate one less hamburger a week, the hunger crisis would be conquered. Yet even while I scoffed at that notion in 1974, my own writing was often taken to be saying the same thing. In the 1975 edition I asked my readers to pretend they were seated in a restaurant, eating an eight-ounce steak—and to appreciate that the grain used to produce the steak could have filled the empty bowls of 40 people in the room.

The first two editions implied that our grain-fed-meat diet denied grain to the hungry abroad who lacked the resources to feed themselves. But as I did research for

Food First

, my view began to shift. I came to learn that virtually every country has the capacity to grow enough food for its people. No country is a hopeless basket case. Moreover, only a minuscule fraction of our food exports ever reach the hungry.

Much of our research for

Food First

focused on the food-producing potential of some of the world’s most densely populated countries, such as Bangladesh, and some of the most agriculturally resource-poor countries, such as the nations south of the Sahara Desert, known as the Sahel.

In Bangladesh, we learned, enough food is already produced to prevent malnutrition; if it had been fairly distributed, grain alone would have provided over 2,200 calories per person per day in 1979.

1

And the stunning agriculture potential of Bangladesh, where rice yields are only half as large as in China, has hardly been tapped. I was struck by the conclusion of a 1976 report to Congress: “The country is rich enough in fertile land, water, manpower and natural gas for fertilizer, not only to be self-sufficient in food but a food exporter, even with its rapidly increasing population size.”

2

We focused on the Sahel because severe famine threatened the region in the years just before we began

Food First

. We saw so many TV images of hungry people dying on desolate, parched earth that we were certain that if ever there were a case of nature-caused famine, this had to be it.

But to our dismay, we learned that with the possible exception of Mauritania (a country rich in minerals), every country in the Sahel actually produced enough grain to feed its total population even during the worst years of the drought of the early 1970s.

3

Moreover, in a number of the Sahelian countries production of

export

crops such as cotton, peanuts, and vegetables actually increased.

4

In researching what became

Diet for a Small Planet

, I was struck by the tremendous abundance in the U.S. food system, and I assumed that many other countries would be forever dependent on our grain exports because they did not have the soil and climate suitable for basic food production. But I learned that while the United States is blessed with exceptional agricultural resources, third world countries are not doomed to be perpetually dependent on U.S. exports.

I learned that what so many Americans are made to see as inevitable third world dependence on grain imports is the result of five forces:

1. A small minority controls more and more of the farmland

. In most third world countries, roughly 80 percent of the agricultural land is, on average, controlled by a tiny 3 percent of those who own land.

5

This minority underuses and misuses the land.

2. Agricultural development of basic foods is neglected, while production for export climbs

. Elites now in control in most third world countries prefer urban industrialization to basic rural development that could benefit the majority. Of 71 underdeveloped countries studied in the mid-1970s, three-quarters allocated less than 10 percent of their central government expenditures to agriculture.

6

Moreover, as the majority of people are increasingly impoverished, the domestic market for basic food shrinks. So food production is oriented toward the more lucrative foreign markets and the tastes of the small urban class. The meager investment in agriculture which does take place is primarily private investment in export crops. In Asia, for example, “the new export-oriented luxury food agribusiness is undoubtedly the fastest growing agriculture sector,” the prestigious

Far Eastern Economic Review

notes. “Fruit, vegetables, seafood and poultry [from southeastern Asian countries] are filling European, American and, above all, Japanese supermarket shelves.”

7

3. More and more basic grains go to livestock

. As the gap between rich and poor widens, basic grains are fed increasingly to livestock in the third world, even in the face of deepening hunger for the majority there. Not only is more and more grain fed to animals, but much land that could be growing basic food is used to graze livestock, often for export. Two-thirds of the agriculturally productive land in Central America is devoted to livestock production, yet the poor majority cannot afford the meat, which is eaten by the well-to-do or exported.

8

4. Poverty pushes up population growth rates

. The poverty and powerlessness of the poor produces large families. The poor must have many children to compensate for their high infant death rate, to provide laborers to supplement meager family income, and to provide the only old age security the poor have. High birthrates also reflect the social powerlessness of women, exacerbated by poverty.

9

5. Conscious “market development” strategies of the U. S. government help to make other economies dependent on our grain

. (See “The Meat Mystique,”

Part II

,

Chapter 3

, to learn how market development works.)

These forces that generate needless hunger are hidden from most Americans, so when they hear that the poorest underdeveloped countries are importing twice as much grain as they did ten years ago, Americans inevitably conclude that scarcity of resources is their basic problem. Americans then urge more food exports, including food aid.

In writing

Food First

, however, we learned that two-thirds of U.S. agricultural exports go to the industrial countries, not the third world, and that most of what does go to the third world is fed to livestock, not to the hungry people. In writing

Aid as Obstacle: Twenty Questions about Our Foreign Aid and the Hungry

, we learned that chronic food aid to elite-based, repressive governments not only fails to reach the hungry in most cases, it actually hurts them. Food aid, we found, is largely a disguised form of economic assistance, concentrated on a handful of governments that U.S. policymakers view as allies. Because food aid is often sold to the people by recipient governments, it serves as general budgetary support, reinforcing the power of these elite-based governments. In 1980, ten countries received three-quarters of all our food aid.

10

Among them were Egypt, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, and South Korea. Notorious for their neglect of the poor, such governments block genuine agrarian reform that could unchain their country’s productive potential. Indonesia, for example, squanders its spectacular oil wealth—$10 billion in 1980—on luxury imports, militarism, and showy capital-intensive industrial projects which don’t even provide many jobs.

What I have just said does not diminish our responsibility to send food to relieve famine, as was needed in Kampuchea in 1980 and Africa in 1981. (Note that disaster and famine relief are only 11 percent of our government’s food aid program.) But even in the face of famine, as in Kampuchea or Somalia, we learned, the U.S. government often operates more out of political than humanitarian considerations—to the detriment of the hungry. Famine relief funds channeled through private voluntary agencies often have a better chance of helping.

In writing

Food First

and the books that followed, I had to learn some painful lessons. In the back of my mind I was always asking, what does all of this mean for the message of

Diet for a Small Planet?

If our food is not getting to the hungry, if our food exports actually prop up some of the world’s most repressive governments, then why exhort Americans to feed less grain to livestock? Why not pour even more of our grain into livestock, so that at least it does not block needed change abroad?

At the same time I was asking myself these questions, I was studying the agricultural system in the United States. In the process,

Diet for a Small Planet

took on new and deeper meaning. The first edition of this book explained how our production system takes abundant grain, which hungry people can’t afford, and shrinks it into meat, which better-off people will pay for. But I didn’t fully appreciate that our production system not only reduces abundance but actually mines the very resources on which our future food security rests.

2.

Like Driving a Cadillac

A

FEW MONTHS

ago a Brazilian friend, Mauro, passed through town. As he sat down to eat at a friend’s house, his friend lifted a sizzling piece of prime beef off the stove. “You’re eating that today,” Mauro remarked, “but you won’t be in ten years. Would you drive a Cadillac? Ten years from now you’ll realize that eating that chunk of meat is as crazy as driving a Cadillac.”

Mauro is right: a grain-fed-meat-centered diet

is

like driving a Cadillac. Yet many Americans who have reluctantly given up their gas-guzzling cars would never think of questioning the resource costs of their grain-fed-meat diet. So let me try to give you some sense of the enormity of the resources flowing into livestock production in the United States. The consequences of a grain-fed-meat diet may be as severe as those of a nation of Cadillac drivers.

A detailed 1978 study sponsored by the Departments of Interior and Commerce produced startling figures showing that

the value of raw materials consumed to produce food from livestock is greater than the value of all oil, gas, and coal consumed in this country

.

1

Expressed another way, one-third of the value of

all

raw materials consumed for all purposes in the United States is consumed in livestock foods.

2

How can this be?

The Protein Factory in Reverse

Excluding exports, about one-half of our harvested acreage goes to feed livestock. Over the last forty years the amount of grain, soybeans, and special feeds going to American

livestock

has doubled. Now approaching 200 million tons, it is equal in volume to all the grain that is now imported throughout the world.

3

Today our livestock consume ten times the grain that we Americans eat directly

4

and they outweigh the human population of our country four to one.

5

These staggering estimates reflect the revolution that has taken place in meat and poultry production and consumption since about 1950.

First, beef. Because cattle are ruminants, they don’t need to consume protein sources like grain or soybeans to produce protein for us. Ruminants have the simplest nutritional requirements of any animal because of a unique fermentation “vat” in front of their true stomach. This vat, the rumen, is a protein factory. With the help of billions of bacteria and protozoa, the rumen produces microbial protein, which then passes on to the true stomach, where it is treated just like any other protein. Not only does the rumen enable the ruminant to thrive without dietary protein, B vitamins, or essential fatty acids, it also enables the animal to digest large quantities of fibrous foodstuffs inedible by humans.

6

The ruminant can recycle a wide variety of waste products into high-protein foods. Successful animal feeds have come from orange juice squeeze remainders in Florida, cocoa residue in Ghana, coffee processing residue in Britain, and bananas (too ripe to export) in the Caribbean. Ruminants will thrive on single-celled protein, such as bacteria or yeast produced in special factories, and they can utilize some of the cellulose in waste products such as wood pulp, newsprint, and bark. In Marin County, near my home in San Francisco, ranchers are feeding apple pulp and cottonseed to their cattle. Such is the “hidden talent” of livestock.

Because of this “hidden talent,” cattle have been prized for millennia as a means of transforming grazing land unsuited for cropping into a source of highly usable protein, meat. But in the last 40 years we in the United States have turned that equation on its head. Instead of just protein factories, we have turned cattle into protein disposal systems, too.

Yes, our cattle still graze. In fact, from one-third to one-half of the continental land mass is used for grazing. But since the 1940s we have developed a system of feeding grain to cattle that is unique in human history. Instead of going from pasture to slaughter, most cattle in the United States now first pass through feedlots where they are each fed over 2,500 pounds of grain and soybean products (about 22 pounds a day) plus hormones and antibiotics.

7

Before 1950 relatively few cattle were fed grain before slaughter,

8

but by the early 1970s about three-quarters were grain-fed.

9

During this time, the number of cattle more than doubled. And we now feed one-third more grain to produce each pound of beef than we did in the early 1960s.

10

With grain cheap, more animals have been fed to heavier weights, at which it takes increasingly more grain to put on each additional pound.

In addition to cattle, poultry have also become a big consumer of our harvested crops. Poultry can’t eat grass. Unlike cows, they need a source of protein. But it doesn’t have to be grain. Although prepared feed played an important role in the past, chickens also scratched the barnyard for seeds, worms, and bits of organic matter. They also got scraps from the kitchen. But after 1950, when poultry moved from the barnyard into huge factorylike compounds, production leaped more than threefold, and the volume of grain fed to poultry climbed almost as much.

Hogs, too, are big grain consumers in the United States, taking almost a third of the total fed to livestock: Many countries, however, raise hogs exclusively on waste products and on plants which humans don’t eat. When Nobel Prize winner Norman Borlaug heard that China had 250 million pigs, about four times the number here, he could hardly believe it. What could they possibly eat? He went to China and saw “pretty scrawny pigs.” Their growth was slow, but by the time they reached maturity they were decent-looking hogs, he admitted in awe. And all on cotton leaves, corn stalks, rice husks, water hyacinths, and peanut shells.

11

In the United States hogs are now fed about as much grain as is fed to cattle.

All told, each grain-consuming animal “unit” (as the Department of Agriculture calls our livestock) eats almost two and a half tons of grain, soy, and other feeds each year.

12

W

HAT

D

O

W

E

G

ET

B

ACK?

For every 16 pounds of grain and soy fed to beef cattle in the United States we only get 1 pound back in meat on our plates.

13

The other 15 pounds are inaccessible to us, either used by the animal to produce energy or to make some part of its own body that we do not eat (like hair or bones) or excreted.

To give you some basis for comparison, 16 pounds of grain has twenty-one times more calories and eight times more protein—but only three times more fat—than a pound of hamburger.

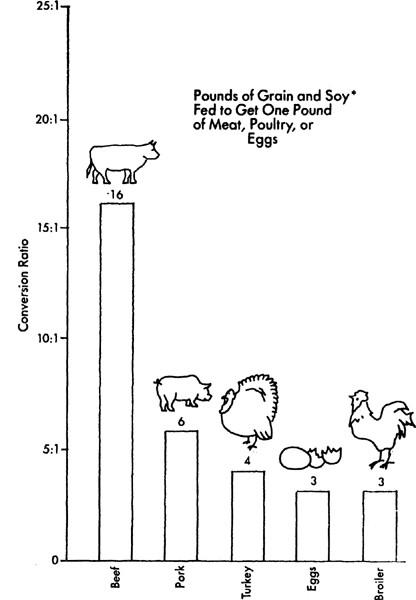

Livestock other than cattle are markedly more efficient in converting grain to meat, as you can see in

Figure 1

; hogs consume 6, turkeys 4, and chickens 3 pounds of grain and soy to produce 1 pound of meat.

14

Milk production is even more efficient, with less than 1 pound of grain fed for every pint of milk produced. (This is partly because we don’t have to grow a new cow every time we milk one.)

Now let us put these two factors together: the large quantities of humanly edible plants fed to animals and their inefficient conversion into meat for us to eat. Some very startling statistics result. If we exclude dairy cows, the average ratio of all U.S. livestock is 7 pounds of grain and soy fed to produce 1 pound of edible food.

15

Thus, of the 145 million tons of grain and soy fed to our beef cattle, poultry, and hogs in 1979, only 21 million tons were returned to us in meat, poultry, and eggs.

The rest, about 124 million tons of grain and soybeans, became inaccessible to human consumption

. (We also feed considerable quantities of wheat germ, milk products, and fishmeal to livestock, but here I am including only grain and soybeans.) To put this enormous quantity in some perspective, consider that 120 million tons is worth over $20 billion. If cooked, it is the equivalent of 1 cup of grain for every single human being on earth every day for a year.

16

Figure 1. A Protein Factory in Reverse

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service, Beltsville, Maryland.

*Soy constitutes only 12% of steer feed and 20 − 25% of poultry.

Not surprisingly,

Diet for a Small Planet’s

description of the systemic waste in our nation’s meat production put the livestock industry on the defensive. They even set a team of cooks to work to prove the recipes unpalatable! (Actually, they had to admit that they tasted pretty good.)

Some countered by arguing that you get

more

protein out of cattle than the humanly edible protein you put in! Most of these calculations use one simple technique to make cattle appear incredibly efficient: on the “in” side of the equation they included only the grain and soy fed, but on the “out” side they include the meat put on by the grain feeding

plus

all the meat the animal put on during the grazing period. Giving grain feeding credit for all of the meat in the animal is misleading, to say the least, since it accounts for only about 40 percent. In my equation I have included only the meat put on the animal as a result of the grain and soy feeding. Obviously all the other meat, put on by forage, would have been there for us anyway—just as it was before the feedlot system was developed. (My calculations are in note 13 for this chapter, so you can see exactly how I arrived at my estimate.)

The Feedlot Logic: More Grain, Lower Cost

On the surface it would seem that beef produced by feeding grain to livestock would be more expensive than beef produced solely on the range. For, after all, isn’t grain more expensive than grass? To us it might be, but not to the cattle producer. As long as the cost of grain is cheap in relation to the price of meat, the lowest production costs per pound are achieved by putting the animal in the feedlot as soon as possible after weaning and feeding it as long as it continues to gain significant weight.

17

This is true in large part because an animal gains weight three times faster in the feedlot on a grain and high-protein feed diet than on the range.

As a byproduct, our beef has gotten fattier, since the more grain fed, the more fat on the animal. American consumers have been told that our beef became fattier because

we

demanded it. Says the U.S. Department of Agriculture: “most cattle are fed today because U.S. feed consumers have a preference for [grain] fed beef.”

18

But the evidence is that our beef became fattier

in spite of

consumer prefence, not because of it. A 1957 report in the

Journal of Animal Science

noted that the public prefers “good” grade (less fatty) beef and would buy more of it if it were available.

19

And studies at Iowa State University indicate that the fat content of meat is not the key element in its taste anyway.

20

Nevertheless, more and more marbled “choice” meat was produced, and “good” lean meat became increasingly scarce as cattle were fed more grain. In 1957 less than half of marketed beef was graded “choice;” ten years later “choice” accounted for two-thirds of it.

21

Many have misunderstood the economic logic of cattle feeding. Knowing that grain puts on fat and that our grading system rewards fatty meat with tantalizing names like “choice” and “prime,” people target the grading system as the reason so much grain goes to livestock. They assume that if we could just overhaul the grading system, grain going to livestock would drop significantly and our beef would be less fatty. (The grading system was altered in 1976, but it still rewards fattier meat with higher prices and more appealing-sounding labels.)

But what would happen if the grading system stopped rewarding fatty meat entirely? Would less fatty meat be produced? Would less grain be fed? Probably only marginally less. As long as grain is cheap in relation to the price of meat, it would still make economic sense for the producer to put the animal in the feedlot and feed it lots of grain. The irony is that, given our economic imperatives that produce cheap grain, most of the fat is an inevitable consequence of producing the cheapest possible meat. We got fatty meat not because we demanded fatty meat but because fatty meat was the cheapest to produce. If we had demanded the same amount of leaner meat, meat prices would have been higher over the last 30 years.

22