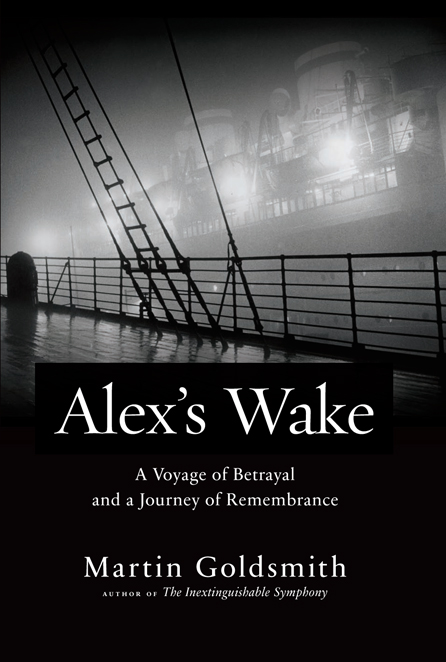

Alex's Wake

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

Copyright © 2014 by Martin Goldsmith

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Epigraph on page vii: From THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS VOL. VIII, copyright ©1977, 1979 by The University of the South. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Design and composition by Eclipse Publishing Services

Set in 12-point Adobe Jenson Pro Light

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2014

ISBN: 978-0-306-82323-7 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

10

Â

9

Â

8

Â

7

Â

6

Â

5

Â

4

Â

3

Â

2

Â

1

To the memory of my brother, Peter, and, once again, to Amy

Contents

ONE

Â

Setting Forth

TWO

Â

Sachsenhagen

FIVE

Â

The Voyage of the

St. Louis

SIX

Â

Boulogne-sur-Mer

SEVEN

Â

Martigny-les-Bains

TEN

Â

Rivesaltes

ELEVEN

Â

Les Milles

FOURTEEN

Â

Coming Home

Â

And I only am escaped alone to tell thee.

âJob

Â

All right, I've told you my story. Now I want you to do something for me. Take me out to Cypress Hill and we'll hear the dead people talk. They do talk there. They chatter together like birds on Cypress Hill, but all they say is one word and that word is “live,” they say, “Live, live, live, live, live!” It's all they've learned, it's the only advice they can give. Just live.

âTennessee Williams

T

HAT TIMELESS

A

MERICAN TRAVELER

, Huckleberry Finn, introduces himself this way: “You don't know about me without you have read a book by the name of

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

; but that ain't no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly.” Some years ago, I made a book by the name of

The Inextinguishable Symphony

and told the story of my father and mother. In that book, my father mostly appeared as a young man named Günther Ludwig Goldschmidt who, by dint of good fortune and dogged persistence, escaped Nazi Germany and arrived on Ellis Island in June 1941. Shortly thereafter, he changed his name to George Gunther Goldsmith, and he and his young wife Rosemary began their lives in The Land of the Free. It's a good book, I think, and I'm proud of it. And, yes, I told the truth, mainly.

I finished writing

The Inextinguishable Symphony

on December 31, 1999, just as the clock crept toward the close of a century as brutal and bloody as any in the history of our glorious and unhappy planet. The book was published in September 2000, and I began what my wife generously calls “The Never-Ending Book Tour.” I'm pleased to say that I have made well over a hundred appearances on behalf of the book, speaking from one end of the United States to the other and in such foreign cities as Toronto, Berlin, and St. Petersburg. I mention these facts not in a spirit of self-aggrandizement so much as to give weight to

the additional fact that in nearly every city I am asked, “So, after writing this book, what has happened to your Jewish identity? And what was your father's reaction to the book?” I'm not sure I realized it at the time, but my attempts to answer those questions represented the first stirrings of the journey that has resulted in the making of this book.

I think that my father had a rather ambivalent reaction to

The Inextinguishable Symphony

. He was pleased at its favorable reception, happy for my opportunities to discuss it, and honored to have been the subject of the book, but I think it also made him profoundly uncomfortable, and in no small measure ashamed. In many ways, Günther Goldschmidt is the hero of the book. George Goldsmith, however, didn't feel like a hero. Mr. Mark Twain would have called that heroic portrait a “stretcher” of the truth, and, much as it pains me to acknowledge it, he would have been right.

George's father, my grandfather Alex Goldschmidt, and his younger brother, my uncle Klaus Helmut Goldschmidt, were two of the more than nine hundred Jewish refugees who attempted to flee Nazi Germany in May 1939 on board an ocean liner called the

St. Louis

. The fate of that ship commanded global attention for a few weeks that springâthe

New York Times

declared it “the saddest ship afloat today”âas it attempted to find safe harbor in an unwelcoming world. After more than a month at sea, my grandfather and uncle found themselves in France, where they would remain for the next three years. They spent time in a number of different settlements, each less hospitable than the last, before being shipped to their deaths at Auschwitz in August 1942.

Alex had spent four years fighting in the muddy, ghastly trenches of the First World War, achieving the distinction of the Iron Cross, First Class from a presumably grateful German government. In the uneasy peace that followed the Great War, he achieved success as a businessman and parlayed his profitable women's clothing store into a lofty position in the emerging society of his adopted hometown of Oldenburg. Never one to allow life's circumstances to dictate terms to him where he could help it, Alex was a man of forthright action and blunt expression. Even while caught in the snares of his French imprisonment, he wrote impassioned letters to those in charge, stating the case for his freedom

and that of his younger son. And he sent letters to his older son, my father, to spur him into action on their behalf.

In his very last letter to George, Grandfather Alex recounted the horrors he and Helmut had endured since boarding the

St. Louis

more than three years earlier. With all the pent-up pain and frustration of his captivity flowing through his pen, Alex concluded, “I have already described our situation for you several times. This will be the last time. If you don't move heaven and earth to help us, that's up to you, but it will be on your conscience.”

My father and mother had managed to emigrate to the United States in June 1941. They had survived as Jews in Germany until then because of their status as musicians in an all-Jewish performing arts organization called the

Kulturbund

. Once in America, they both found menial jobs: my mother as a domestic, cooking and cleaning houses for twelve dollars a week, and my father working in a factory where he cut zippers out of discarded pants and polished them on a wheel, reconditioning them so that they could serve again in the flies of new trousers. For this, he was paid fourteen dollars a week. They didn't have much, but they occasionally sent as much as twenty-five dollars, nearly a full week's salary, via Quaker intermediaries to the camps in France to try to ease the burden of Alex and Helmut.

But did my father do as much as he could have on his family's behalf? Did he, as his father had implored him, “move heaven and earth”? Probably not. In the late summer of 1941, my parents landed jobs performing at a music festival in Columbia, South Carolina. They took the train from their home in New York City down to Columbia, passing through Washington, D.C., on their journeys south and north. Neither time did my father disembark in the capital to visit the halls of Congress, where he might have found an important ally who could have helped him to fill out the proper form or contact the right immigration officer who might have reached the exact authority in France in time to ensure that Alex and Helmut never boarded that fateful train to Auschwitz. There were reasons aplenty why every effort under the sun might have failed to win his family's freedom, but the inescapable fact remains that Alex begged his son to save his life and my father failed to do so.