Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (44 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

6.58Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

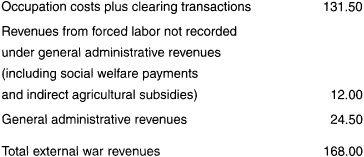

Table 6: General Administrative Revenues/Remaining Revenues (in Billions of Reichsmarks)

Based on these calculations, approximately 24.5 billion reichsmarks were acquired by theft from “foreigners.” The German finance minister recorded these funds as “general administrative revenues.” That figure includes credits for transfers of wages to the families of forced laborers as well as approximately 4 billion reichsmarks robbed from German Jews after 1939. It also takes into account sums paid by the German military commander in Belgium from the proceeds of the Aryanization campaign, purchases made in reichsmarks by German firms in German-dominated Europe, and many other sources of income.

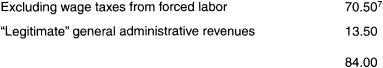

Adding revenues from forced labor and general administrative revenues to Germany’s income from mandatory tributes, advances on clearing debts, and war contributions from allied states produces table 7.

Table 7: External War Revenues (in Billions of Reichsmarks)

This balance sheet of larceny contains several billion marks in double bookings. In certain cases the goods and services procured through state theft were paid for twice: money to procure goods was sometimes diverted from occupation budgets, which then had to be replenished. German businesses that bought foreign raw materials, machinery, or unfinished products to build artillery, warplanes, or transport vehicles enjoyed the sae advantage. These sources of income have been included in “external revenues” because they did not in any way disadvantage German buyers. Indeed, buyers profited from such dirty dealing.

On the other hand, several categories of income are not included in the total of Germany’s external war revenues. In the absence of reliable data, the final figure does not reflect the amount of business and commercial taxes saved by using forced labor and looted factories, raw materials, and unfinished products. The accuracy of the individual figures and estimates above can be debated. The overall picture, however, remains clear.

By even the most conservative estimates, the Third Reich extracted no less than 170 billion reichsmarks of its ongoing war revenues from “foreign” sources. That figure is ten times what the Reich raised in 1938 and the equivalent today of some 1.7 to 2 trillion euros ($2-2.2 trillion). The policy of plunder was the cornerstone for the welfare of the German people and a major guarantor of their political loyalty, which was first and foremost based on material considerations. The unshakable alliance between the state and the people was not primarily the result of cleverly conceived party propaganda. It was created by means of theft, with the spoils being redistributed according to egalitarian principles among the members of the ethnically defined

Volk

.

Volk

.

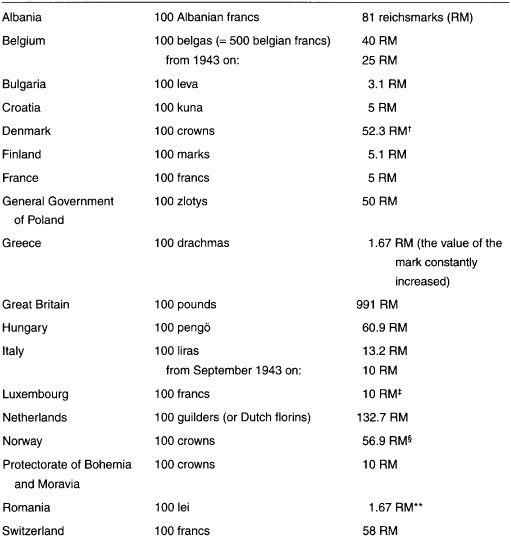

In determining the relation between internal and external sources of revenue, routine expenditures have to be factored out. They are by no means part of additional wartime spending. For the German Reich, those costs, which exclude all war-related spending, can be fixed at around 20 billion reichsmarks annually and include the normal costs of government, basic social services, and the maintenance of a defensive army. With these expenditures factored out, it emerges that the German treasury recorded the remarkably low figure of 77 billion reichsmarks in internal war revenues, earned via direct and indirect taxation during the course of World War II. (That figure excludes wage tax revenues from forced labor, the contributions paid by the General Government and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and the portion of general administrative revenues earned through plunder.) Adding “legitimate” general administrative revenues yields the following total:

Table 8: Total War Revenues from within the Reich (in Billions of Reichsmarks)

These calculations use the lowest available estimates of looted or extracted external resources and the highest credible ones for German war-tax revenues. The German contribution to the ongoing costs of war can therefore be estimated as, at most, one-third—while external sources account for at least two-thirds of wartime revenues.

The upper classes forked over the lion’s share of these increased internal revenues. Low- and middle-income Germans (about two-thirds of all taxpayers) paid increased wartime taxes on tobacco, beer, and sparkling wine. These amounted to around 12 billion reichsmarks, or around 16 percent of internal wartime tax revenues. Add to that figure the extension of working hours, which resulted in increased wage-tax revenues beyond those of slave labor. On the other hand, the wage tax burden was lowered for individual earners of paychecks since, as of the fall of 1940, overtime, night, and holiday wages were declared tax-exempt. Simultaneously, revenues from income, business, and windfall profits taxes increased dramatically. In 1939, the Reich took in 2.6 billion marks in wage taxes, while earning 4.4ion from income taxes on the self-employed. Assuming that the latter figure would have been around 4 billion for 1939 had Germany not gone to war in September, we can calculate that the German war chest earned at least 16 billion reichsmarks from steeper additional taxation of the private revenues of the self-employed between September 1939 and early 1945. Wartime increases in corporate taxes can be estimated at around 12 billion reichsmarks. In addition there were revenues from taxes on war-related profits, which accounted for at least 4 billion reichsmarks, and revenues from property taxes of around 8 billion. That yields a total of 40 billion reichsmarks that relatively affluent Germans contributed to the war effort.

8

8

In terms of all wartime revenues, internal and external, low- and middle-income Germans, who together with their families numbered some 60 million, accounted for no more than 10 percent of the total sum. More affluent Germans bore 20 percent of the burden, while foreigners, forced laborers, and Jews were compelled to cover 70 percent of the funds consumed every day by Germany during the war. The middle and working classes derived advantages from the Third Reich’s dual emphasis on race and class: “wartime socialism” combined with a sense of racial superiority and imperial adventurism guaranteed solid support for the regime well into the second half of the war. Material self-interest suppressed any acknowledgment of the criminal basis of the Nazi social welfare state among the majority of Germans.

Two clear conclusions emerge from these elaborate calculations. First, at least two-thirds of German war revenues were earned from foreign or “racially foreign” sources.* Second, the remaining third of the costs were distributed extremely unequally between the various economic classes in German society. One-third of taxpayers bore more than two-thirds of the burdens of war, while the vast majority of Germans paid only the small amount left over.

The discrepancy in the tax burdens placed on wage laborers and on businessmen is even more glaring. As described in earlier chapters, the average working-class family in Germany was never forced to pay any direct war taxes, and even the increased duties on beer and tobacco products were balanced out by unusually generous military pay scales and support payments to soldiers’ families. On average, the vast and not particularly affluent majority of Germans enjoyed more disposable income during the war than they had before it.

The subject of discussion here has been war-related revenues, which, up until August 1944, covered around half of Germany’s wartime expenditures. The rest was financed on credit. The next chapter discusses how the Third Reich raised that credit on German financial markets and how it planned to saddle conquered countries with the repayments on those loans, once Germany had emerged victorious in World War II.

CHAPTER 12

Speculative Politics

Silent and Illusory

While the proportion of costs for World War II that Germany was able to defray without credit was far greater than it had been in World War I, the Reich finance minister still had to borrow significant amounts of money. This was done through what finance experts call “silent” or “invisible” loans. The Nazi regime did not try to convince the populace to buy long-term war bonds, as the Wilhelmine government did between 1914 and 1918. Instead, it ed money directly from credit institutions, using short-term war bonds—without any legal fanfare and unbeknownst to investors—as collateral.

Starting in 1936, savings banks, building societies, credit unions, and insurance companies underwent a gradual and largely unnoticed transformation into reservoirs of state capital. The same was true of pension funds, which at the time possessed large capital reserves. With no evident resistance, bankers agreed to take state bonds into their portfolios. They were, in effect, making a long-term investment with the mostly short-term savings of their customers. The secret to the success of the “silent loans” was the appearance that the transactions were voluntary. As early as January 1940, the German press was ordered not to mention the possibility of a compulsory wartime freeze on savings accounts.

1

A regulation to this effect was rejected by the Nazi leadership as “completely wrongheaded and politically unviable.” The German worker was to be kept “under the impression, at least, that he was not being restricted in his ability to do what he wanted with wage-earned income” and that the state had no intention “of taking anything in any form away from him.”

2

Göring’s financial adviser Otto Donner praised the system for its closed circulation of capital, which was based on the fact that “the recipient of income takes that income, which he cannot use legally, to the bank. Credit institutions transfer the money to the finance minister in return for promissory notes.”

3

1

A regulation to this effect was rejected by the Nazi leadership as “completely wrongheaded and politically unviable.” The German worker was to be kept “under the impression, at least, that he was not being restricted in his ability to do what he wanted with wage-earned income” and that the state had no intention “of taking anything in any form away from him.”

2

Göring’s financial adviser Otto Donner praised the system for its closed circulation of capital, which was based on the fact that “the recipient of income takes that income, which he cannot use legally, to the bank. Credit institutions transfer the money to the finance minister in return for promissory notes.”

3

The “silent” transformation of the contents of more than 40 million savings accounts and other forms of investment into state bonds kept a continuous supply of money flowing into the Reich treasury. There the money was spent on the war and thus literally destroyed.

4

Earlier chapters examined how cash was exchanged, primarily by Wehrmacht soldiers, for goods and services in occupied territories. This was a way of partially restoring the equilibrium, which had been disturbed by the war, between available goods and paper money. Yet a significant amount of money remained in private hands, and the regime wanted Germans to save as much as possible. This, in turn, necessitated rigid price and wage controls, and the suppression of domestic black markets.

4

Earlier chapters examined how cash was exchanged, primarily by Wehrmacht soldiers, for goods and services in occupied territories. This was a way of partially restoring the equilibrium, which had been disturbed by the war, between available goods and paper money. Yet a significant amount of money remained in private hands, and the regime wanted Germans to save as much as possible. This, in turn, necessitated rigid price and wage controls, and the suppression of domestic black markets.

SILENT LOANS did not affect only Germans with savings accounts. Reich bank commissioners also compelled financial institutions in occupied countries to buy up German bonds to help finance the war. By the end of the war, German bonds accounted for more than 70 percent of the investments of Czech banks.

5

In France, “enemy investments” were converted into bonds that the French government had to issue in order to pay for German occupation costs.

6

Because a significant proportion of the enormous contributions demanded of occupied countries were raised in the form of state bonds, the various national banks and financial administrations of those countries were under constant pressure to subjugate their own national money markets to the interests of German wartime finances. Organizing this complex system was one of the main tasks of the German bank commissioners.

5

In France, “enemy investments” were converted into bonds that the French government had to issue in order to pay for German occupation costs.

6

Because a significant proportion of the enormous contributions demanded of occupied countries were raised in the form of state bonds, the various national banks and financial administrations of those countries were under constant pressure to subjugate their own national money markets to the interests of German wartime finances. Organizing this complex system was one of the main tasks of the German bank commissioners.

Other books

The Promise of Home by Darcie Chan

Treva's Children by David L. Burkhead

Darkroom by Graham Masterton

Deserter by Mike Shepherd

The Time Baroness (The Time Mistress Series) by Georgina Young-Ellis

Pursuit: Brandon & Carly (Mafia Ties Book 4) by Fiona Davenport

Leaving Lancaster by Kate Lloyd

Restless (Element Preservers, #4) by Linwood, Alycia

Till Death by Alessandra Torre, Madison Seidler

A Good and Happy Child by Justin Evans