Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (26 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

7.53Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

This linear calculation of potential increases in subsidies is based on an average annual increase in index points of 37.5. (The corresponding numbers for 1942, 1943, 1944, and 1945 would have been 250, 287.5, 325, and 362.5, respectively.) If one takes into account the actual decrease to 150 in 1942 but continues to use this rate of growth, subsidies would have reached 187.5 index points in 1943, 225 in 1944, and 262.5 in 1945. Extrapolating from these figures, one sees that the Reich “saved” approximately 2.2 billion reichsmarks between 1942 and May 1945. Those savings can be traced back to the denial of social benefits to forced laborers and the mass murder of Jewish claimants.

Not surprisingly, the huge influx of forced laborers in 1942 is also reflected in the wage tax revenues taken in by the Reich.

Table 2: Wage Tax Revenues, 1938–43

The figures in table 2 show that wage tax revenues more than doubled between 1938 and 1943. There are two major jumps: 26 percent from 1938 to 1939 and 42 percent between 1940 and 1941. The first increase reflects the incorporation of Austria and Sudeten Czechoslovakia into the Reich, as well as lengthened working hours after the start of the war.

The second can be traced to the massive use of forced laborers in German industry. Without that influx, revenues after 1940 could hardly have increased by any more than 5 percent annually and would have diminished as Germany’s wartime fortunes began to fail. In monetary terms, without forced labor, projected tax revenues between 1940 and the first quarter of 1945 would have totaled around 17.3 billion reichsmarks. The actual proceeds were, of course, far higher since forced labor was used more intensively in the final stages of the war. Assuming a further 10 percent increase in wage tax revenues in 1944 and the first quarter of 1945 (to reflect the increased reliance on forced labor), actual proceeds probably totaled 23.8 billion reichsmarks from 1940 through early 1945. The difference between the two figures—6.5 billion marks—reflects a conservative estimate of the amount by which German taxpayers benefited from revenues generated by taxes on forced labor.

New Central Banks

Except for the chaotic weeks of German retreat in the final phase of World War II, the Wehrmacht “paid” for practically all its needs in Northern, Western, and Southern Europe in RKK certificates or local currencies. Consequently, the extent of the larceny can be roughly measured in Wehrmacht expenditures. The same, however, was not true for the German-occupied parts of the Soviet Union. There, the Wehrmacht seldom used money or certificates to make acquisitions A significant portion of what it needed was simply requisitioned through obscure “receipts” or without any paperwork at all. According to an order from the Wehrmacht directorate, “all nonmilitary or private property up to a value of 1,000 reichsmarks is to be paid for in cash.” For larger acquisitions, preprinted acknowledgments of receipt were to be filled out. These expenses included food, which was “under no circumstances to be paid for in cash.”

21

But the question arises: what did private property mean in a system where most everything had been collectivized? Unlike other occupied countries, the Soviet Union was plundered in ways that cannot be measured in officially recorded transactions.

22

21

But the question arises: what did private property mean in a system where most everything had been collectivized? Unlike other occupied countries, the Soviet Union was plundered in ways that cannot be measured in officially recorded transactions.

22

On June 9, 1941, Reichsbank director Max Kretzschmann gave the administrative council of the Reich Credit Banks a top-secret briefing on the short-term tasks they would soon face. Reichsbank officials had already organized six mobile credit banks to serve the immediate needs of the troops.

23

On June 12, 1941, the order came through, “in light of planned military operations in the East,” to increase the number of pre-ordered RKK certificates “by 1 billion to 1½ billion reichsmarks.” This was to be carried out with “maximum speed.”

24

Ten days later, Operation Bar-barossa began. As the pace of the German advance into the Soviet Union slowed in late July, the Reich treasury printed some 10 billion counterfeit rubles. These, however, were never used.

25

No sooner had German units moved through a given area than RKK employees had Russian coins melted down “in line with the European mobilization of metals.”

26

23

On June 12, 1941, the order came through, “in light of planned military operations in the East,” to increase the number of pre-ordered RKK certificates “by 1 billion to 1½ billion reichsmarks.” This was to be carried out with “maximum speed.”

24

Ten days later, Operation Bar-barossa began. As the pace of the German advance into the Soviet Union slowed in late July, the Reich treasury printed some 10 billion counterfeit rubles. These, however, were never used.

25

No sooner had German units moved through a given area than RKK employees had Russian coins melted down “in line with the European mobilization of metals.”

26

The administrative council had already met on June 9 to discuss how “a new bank of issue—the Moscow Reserve Bank—could be grafted onto the Russian banking system.” The launch of the new bank, it was envisioned, would take about three months and would enable the Reich to print rubles that were legal tender. Even before the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Kretzschmann had weighed the option of initially introducing various forms of currency. “Should the occupied part of Russia be divided up into governmentally distinct districts,” he wrote, “it would require the establishment of several banks of issue.”

27

27

One day later, on June 10, 1941, another top-secret meeting took place in the Finance Ministry. The subject was “the imminent eastern deployment.” The participants discussed issuing credit to those German firms that would be responsible for restoring industrial and agricultural production after the invasion—a major concern for German troops. According to the minutes of the meeting, Finance Ministry administrators assumed that most production facilities “would be destroyed before falling into German hands.” Participants debated how to raise the collateral for loans to repair damaged industrial infrastructure. Reserves of natural resources were ill suited to this purpose, the officials agreed, “since petroleum and mining and agricultural products were, as per orders, to be transported back to Germany.” To solve the problem, the directors of the future Reich Credit Banks in the Soviet Union were instructed to forgo demands for collateral and issue unsecured loans. It was the only way, the Finance Ministry concluded, “to extract the maximum amount possible.”

28

As the invasion and occupation progressedReich Credit Banks would issue tens of millions of marks in loans to firms involved in the occupied Soviet Union.

28

As the invasion and occupation progressedReich Credit Banks would issue tens of millions of marks in loans to firms involved in the occupied Soviet Union.

But the central bank that issued the ruble was in Moscow, which was not under German control. Hence, the administrative council of the Reich Credit Banks came out in the late fall of 1941 in favor of issuing a new currency, “the eastern crown, with a value of two crowns to the mark.” A member of the Reichsbank board of directors, Maximilian Bernhuber, was chosen to oversee the founding of the new central bank. But the project stalled. Leading German civilian administrators in the Baltic States lobbied against the idea, saying it would upset the local populace. And as time passed the military objective of securing the front lines took top priority.

29

29

But another Reichsbank plan to introduce a new currency, the kar-bowanez, for Ukraine, was a success. The law creating the Central Currency Bank of Ukraine (ZNU) came into force on June 1,1942. The bank was modeled on the central bank the Nazi regime had set up for the Polish General Government. The influence of German occupiers on currency policies was “ensured by the fact that the two directors of the Currency Bank were to be appointed by the Reichsbank.”

30

As in the case of other regional currency programs, the finance minister demanded that rubles exchanged in Ukraine for the new banknotes “be transferred without compensation to the main administration of the Reich Credit Bank, so as to serve the interests of the Reich.”

30

As in the case of other regional currency programs, the finance minister demanded that rubles exchanged in Ukraine for the new banknotes “be transferred without compensation to the main administration of the Reich Credit Bank, so as to serve the interests of the Reich.”

The exploitation of compulsorily exchanged currency was common practice in German-occupied Europe. The Finance Ministry had used the same procedure to confiscate French francs in Alsace-Lorraine and rubles in East Galicia after that province was taken from the Soviet Union and added to the Polish General Government in 1941.

31

From the latter annexation, the Reich had taken in some 340 million rubles, which the new bank of issue in Cracow handed over for “utilization.”

32

Moreover, when the Reich itself annexed parts of Poland in 1940, German state bankers had kept some 660 million zlotys that Poles had been forced to exchange for reichsmarks. That money was “appropriated in its entirety via the Reich Credit Banks in Poland and the bank of issue in Poland.” A Reichsbank representative boasted: “A sum equaling more than 300 million marks was extracted for the Reich. Although the Reich was required to use it to redeem Polish banknotes in the annexed eastern territories, thereby recording a loss, we were still able to transform it into a kind of contribution to the war costs from the rest of Polish territory.”

33

In April 1940, after handing over daily business operations to the bank of issue in Cracow, the Reich Credit Banks kept 306 million zlotys, the equivalent of 153 million reichsmarks, which had remained unspent. Schwerin von Krosigk commented dryly: “I do not overlook the fact that the realization of zloty assets I have approved contributes, in a relatively imperceptible form recognizable only to experts, to the burdens on the Polish economy.”

34

Representatives of the German Reich used these sums of money in the remaining franc, ruble, and zloty zones to buy up goods that would otherwise have had to be paid for with funds set aside for occupation costs.

31

From the latter annexation, the Reich had taken in some 340 million rubles, which the new bank of issue in Cracow handed over for “utilization.”

32

Moreover, when the Reich itself annexed parts of Poland in 1940, German state bankers had kept some 660 million zlotys that Poles had been forced to exchange for reichsmarks. That money was “appropriated in its entirety via the Reich Credit Banks in Poland and the bank of issue in Poland.” A Reichsbank representative boasted: “A sum equaling more than 300 million marks was extracted for the Reich. Although the Reich was required to use it to redeem Polish banknotes in the annexed eastern territories, thereby recording a loss, we were still able to transform it into a kind of contribution to the war costs from the rest of Polish territory.”

33

In April 1940, after handing over daily business operations to the bank of issue in Cracow, the Reich Credit Banks kept 306 million zlotys, the equivalent of 153 million reichsmarks, which had remained unspent. Schwerin von Krosigk commented dryly: “I do not overlook the fact that the realization of zloty assets I have approved contributes, in a relatively imperceptible form recognizable only to experts, to the burdens on the Polish economy.”

34

Representatives of the German Reich used these sums of money in the remaining franc, ruble, and zloty zones to buy up goods that would otherwise have had to be paid for with funds set aside for occupation costs.

The new Ukrainian currency increased the number of banknotes in circulation in the occupied Soviet Union without the Reich’s having to resort to forgery. It also led to an immediate devaluaon of rubles that had been hoarded in Ukraine. In Germany’s financial press, the new money was praised as contributing to a “healthy price and currency ratio.”

35

Yet Ukraine did not suffer from money hoarding, as German officials had suggested it would in justifying the new currency; it suffered from the greed of its occupiers. The new banknotes offered numerous opportunities for Germans to exploit Ukraine and exacerbated the very problems they were nominally meant to combat. When Ukrainians tried to exchange large-denomination ruble notes for karbowanez, the branches of the ZNU did not pay out in cash. Rather they credited the amount to frozen bank accounts, which account holders were not allowed to access.

35

Yet Ukraine did not suffer from money hoarding, as German officials had suggested it would in justifying the new currency; it suffered from the greed of its occupiers. The new banknotes offered numerous opportunities for Germans to exploit Ukraine and exacerbated the very problems they were nominally meant to combat. When Ukrainians tried to exchange large-denomination ruble notes for karbowanez, the branches of the ZNU did not pay out in cash. Rather they credited the amount to frozen bank accounts, which account holders were not allowed to access.

The official rationale for this policy was “to curb excess spending power among the native populace.”

36

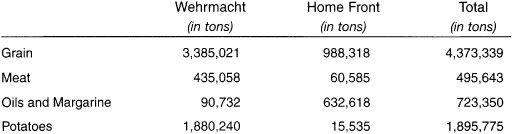

In reality, the sums confiscated were transferred via the Reich Credit Banks and the Wehrmacht directorates to German soldiers and black marketeers in those parts of the occupied Soviet Union where the ruble was still legal tender. The money was used to buy up massive amounts of food. (Only a small portion of it was shipped back to Germany between 1942 and 1943—most was exported to the Wehrmacht’s other theaters of operation.) The Ministry for Occupied Eastern European Territories, concerned about maintaining a functioning economy in Ukraine, implored the Finance Ministry to pay for these supplies, but that appeal fell on deaf ears.

37

36

In reality, the sums confiscated were transferred via the Reich Credit Banks and the Wehrmacht directorates to German soldiers and black marketeers in those parts of the occupied Soviet Union where the ruble was still legal tender. The money was used to buy up massive amounts of food. (Only a small portion of it was shipped back to Germany between 1942 and 1943—most was exported to the Wehrmacht’s other theaters of operation.) The Ministry for Occupied Eastern European Territories, concerned about maintaining a functioning economy in Ukraine, implored the Finance Ministry to pay for these supplies, but that appeal fell on deaf ears.

37

The result of the German spending spree was that occupied Ukraine was constantly having to print more money. In February 1943, the new currency was barely seven months old, but the financial division of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine was already describing the situation as “extremely critical.” The amount of money in circulation had risen by 80 percent within the space of a few months. The currency, which was becoming worthless, had flowed from “the pockets of the Wehrmacht and its employees” into the hands of “the local populace.”

38

In 1942, one bank official reported, “up to 90 percent of occupation costs had to be covered with treasury bonds from the ZNU”—in other words, by printing more money.

39

38

In 1942, one bank official reported, “up to 90 percent of occupation costs had to be covered with treasury bonds from the ZNU”—in other words, by printing more money.

39

Ordinary German Consumers

Germany was unable in either the First or the Second World War to produce enough food to meet its own needs. With the utmost effort, the Nazi leadership succeeded in producing 83 percent of what it required domestically, but imports—especially of cooking oils and feed for livestock—remained necessary in order to keep the populace well nourished. Germany’s dependence on foreign trade meant that the British fleet could easily put pressure on the Reich with blockades, and the collateral effects of war brought decreased harvests and further hindered efforts toward self-sufficiency. The needs of the munitions industry led to unavoidable shortages in artificial fertilizer, which required the same chemicals needed for the production of gunpowder. There were also shortages of agricultural manpower, as well as of horses, tractors, machinery, and fuel. It was more difficult to ensure the timely delivery of seeds to maximize harvest yields. To combat one of these problems, the Nazi leadership decided shortly after the beginning of the war to use Polish labor in German agriculture.

The Reich Food Ministry had gotten a head start in dealing with the anticipated shortfalls. As early as 1936, ministry officials saw to the stockpilireserves of grain and the building of new silos and warehouses, using subsidies and tax breaks as incentives to get private industry involved.

40

Göring viewed such facilities as “an indirect form of armament.” In the summer of 1938, to accelerate preparations, he appointed the highly efficient state secretary of the Food Ministry, Herbert Backe, to oversee the expansion of grain-storage facilities.

41

By June 30, 1939, Germany had 5.5 million tons of grain reserves, and the figure remained constant a year later. But by June 30, 1941, the reserves had dwindled to 2 million tons; a year later they were down to a meager 670,000. In response, officials at an emergency meeting called by Göring in August 1942 decided to step up Germany’s extraction of food from occupied countries. As a result, Backe was able to get grain reserves back up to 1.2 million tons in 1943 and 1.7 million in 1944.

42

40

Göring viewed such facilities as “an indirect form of armament.” In the summer of 1938, to accelerate preparations, he appointed the highly efficient state secretary of the Food Ministry, Herbert Backe, to oversee the expansion of grain-storage facilities.

41

By June 30, 1939, Germany had 5.5 million tons of grain reserves, and the figure remained constant a year later. But by June 30, 1941, the reserves had dwindled to 2 million tons; a year later they were down to a meager 670,000. In response, officials at an emergency meeting called by Göring in August 1942 decided to step up Germany’s extraction of food from occupied countries. As a result, Backe was able to get grain reserves back up to 1.2 million tons in 1943 and 1.7 million in 1944.

42

Other books

The X-Club (A Krinar Story) by Zaires, Anna, Zales, Dima

Playing Games by Jill Myles

Fall From Grace by Menon, David

Trial by Desire by Courtney Milan

First Down (Texas Titans #3) by Cheryl Douglas

Games (Timeless Series) by Loyd, Sandy

Heart of Stars by Kate Forsyth

Pushing Up Daisies by Melanie Thompson

Deception (Carrington Hill Investigations Book 1) by Allenton, Kate

Bad Boyfriend by K. A. Mitchell