Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (22 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

2.47Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In addition to extorting heavy contributions, Germany stole Belgian gold. In 1941, the Vichy regime in France agreed to transport from Dakar to Marseille forty-one tons of gold that the legitimate Belgium government had succeeded in shipping to French colonies in West Africa. In Marseille it was handed over to a representative of the Reichsbank.

18

Under international law, however, Germany could not simply confiscate gold reserves belonging to another nation. In February 1941, aft consultation with Göring’s state secretary, Erich Neumann, occupation authorities invented the pretense of “external occupation costs” incurred by Belgium. The concocted expenses were to be paid out of the Belgian treasury. “Open seizure,” Reich bureaucrats maintained, “is better than covert confiscation.”

19

On July 3, 1941, the administrative council of the Reich Credit Bank in Belgium reached the following decision: “As an advance payment for external occupation expenses, Belgium is to transfer ownership of those gold reserves currently held in Berlin. This demand, however, will be made known to Belgians only at a later date.”

20

The forty-one tons of gold were worth more than a half billion reichsmarks, but their practical value for the German war economy was far greater since gold was the only means of payment the Reich could use to purchase scarce resources in noncombatant countries like Spain, Portugal (tungsten), Sweden (steel, ball bearings), Switzerland (weapons, transport vehicles), and Turkey (chrome).

18

Under international law, however, Germany could not simply confiscate gold reserves belonging to another nation. In February 1941, aft consultation with Göring’s state secretary, Erich Neumann, occupation authorities invented the pretense of “external occupation costs” incurred by Belgium. The concocted expenses were to be paid out of the Belgian treasury. “Open seizure,” Reich bureaucrats maintained, “is better than covert confiscation.”

19

On July 3, 1941, the administrative council of the Reich Credit Bank in Belgium reached the following decision: “As an advance payment for external occupation expenses, Belgium is to transfer ownership of those gold reserves currently held in Berlin. This demand, however, will be made known to Belgians only at a later date.”

20

The forty-one tons of gold were worth more than a half billion reichsmarks, but their practical value for the German war economy was far greater since gold was the only means of payment the Reich could use to purchase scarce resources in noncombatant countries like Spain, Portugal (tungsten), Sweden (steel, ball bearings), Switzerland (weapons, transport vehicles), and Turkey (chrome).

The following illustrations come from a secret report by the German military administration in Belgium entitled “Belgium’s Contributions to the German War Economy” March 1, 1942. (Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, Freiburg in Breisgau)

The text reads: “Shipments of gold from Belgium for holding at the Reichsbank, compared with the Reichsbank’s known gold reserves. To be delivered, 223 million reichsmarks. Already delivered, 335 million reichsmarks. Total, 558 million reichsmarks. Known gold reserves at the Reichsbank, 76 million reichsmarks.”

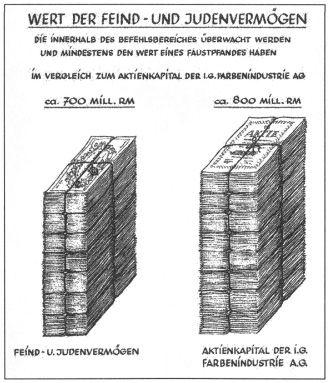

“Values of assets from enemies and Jews that are controlled within Germany’s area of command and have at least mortgage value, compared with the capital stock of I. G. Farben. Ca. 700 million reichsmarks: assets from enemies and Jews. Ca. 800 million reichsmarks: capital stock of I. G. Farben.”

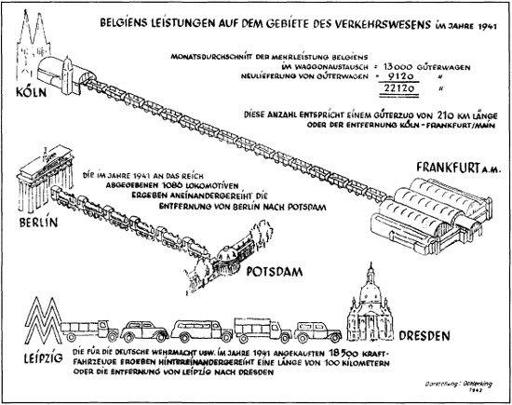

“Belgium’s contribution in 1941 to German transportation. Monthly average in used freight cars, 13,000; new deliveries, 9,120; total, 22,120. This number is the equivalent of a 210-kilometer-long freight train, or the distance between Cologne and Frankfurt am Main. Lined up in a row, the 1,086 locomotives delivered to the Reich in 1941 would stretch from Berlin to Potsdam. Lined up in a row, the 18,500 motor vehicles purchased by the Wehrmacht in 1941 would stretch 100 kilometers in length, or the distance between Leipzig and Dresden.”

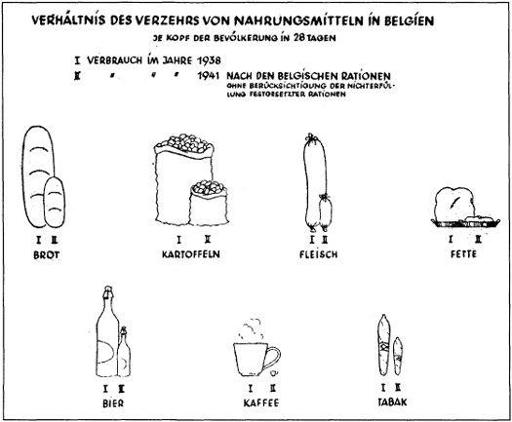

“Per capita food consumption in Belgium, every 28 days. I. Consumption in 1938. II. Consumption in 1941 (unfulfilled rations not taken into account). Bread. Potatoes. Meat. Shortening. Beer. Coffee. Tobacco.”

The following year, the Reichsbank protested the planned announcement of the transfer of ownership, citing currency concerns, specifically the need to pretend that the Belgian franc was still covered by gold reserves. The Foreign Office, on the other hand, wanted to publicize the act of theft, on the assumption that with the end of the war all occupied countries would be presented with a bill for external occupation costs, which would include weapons production in Germany and the maintenance of soldiers’ filies.

21

In Belgium’s case, those debts would be balanced against the gold reserves and debts from German clearing “balances.”

22

In the end, no such complicated declaration was formulated. Instead, on October 9, 1942, the head of the finance department in Berlin and Brandenburg simply appropriated the gold that had been stolen from Belgium, with French help, in the name of the German Reich. The ostensible legal basis was the Reich Contribution Law

(Reichsleistungsgesetz)

of September 1939, which ordered the mandatory exchange of gold, as well as stock and bond certificates, for reichsmarks. In accordance with this legislation, the Reichsbank compensated the national bank of Belgium with a half billion reichsmarks, which were deposited, however, in a frozen account accessible only to the German state.

23

The trade division of the Foreign Office reported to State Secretary Ernst von Weizsäcker and Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop: “With that, thanks to the efforts of the Foreign Office and in particular envoy [Hans-Richard] Hemmen, gold valued at 550 million reichsmarks has been officially transferred to the possession of the Reich.”

24

21

In Belgium’s case, those debts would be balanced against the gold reserves and debts from German clearing “balances.”

22

In the end, no such complicated declaration was formulated. Instead, on October 9, 1942, the head of the finance department in Berlin and Brandenburg simply appropriated the gold that had been stolen from Belgium, with French help, in the name of the German Reich. The ostensible legal basis was the Reich Contribution Law

(Reichsleistungsgesetz)

of September 1939, which ordered the mandatory exchange of gold, as well as stock and bond certificates, for reichsmarks. In accordance with this legislation, the Reichsbank compensated the national bank of Belgium with a half billion reichsmarks, which were deposited, however, in a frozen account accessible only to the German state.

23

The trade division of the Foreign Office reported to State Secretary Ernst von Weizsäcker and Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop: “With that, thanks to the efforts of the Foreign Office and in particular envoy [Hans-Richard] Hemmen, gold valued at 550 million reichsmarks has been officially transferred to the possession of the Reich.”

24

Meanwhile, France was taking care to protect its own gold reserves. The Banque de France repeatedly transferred parts of those reserves to banks in Switzerland to keep them from falling into German hands.

25

Göring’s associates in Berlin who were responsible for keeping tabs on foreign gold took a relaxed attitude toward France’s activities. “In an emergency,” one of them remarked, the Swiss holdings “could be relatively easily commandeered to serve the Reich’s interests.”

26

25

Göring’s associates in Berlin who were responsible for keeping tabs on foreign gold took a relaxed attitude toward France’s activities. “In an emergency,” one of them remarked, the Swiss holdings “could be relatively easily commandeered to serve the Reich’s interests.”

26

According to German calculations, the Belgian state spent 83.3 billion Belgian francs on the needs of its civilian population during the four years of German occupation. In the same period, German occupiers expropriated 133.6 billion francs in currency and goods, including clearing advances. And that sum does not include the theft of Belgian gold reserves, the confiscated assets of Belgian Jews, and other forms of plunder that are difficult to quantify. When they were driven out by the Allies in 1944, the Germans left behind a country that was economically shattered.

27

27

Holland without Borders

With its 8.8 million inhabitants, Holland was slightly larger in population than Belgium. Occupation costs imposed there between 1940 and 1942 officially amounted to 100 million guilders per month (the equivalent today of more than $1.5 billion), which were transferred to the Wehrmacht High Command. In addition, 3 million guilders were to be paid monthly to the Reich commissioner, whose small staff oversaw the administration of the Netherlands.

28

The exchange rate between the guilder and the reichsmark was set at 1 to 1.33. But the Wehrmacht often exceeded the official limit on occupation costs by more than 20 percent.

29

The demands were devastating in a country whose total state expenditures in 1939 had amounted to only 1.4 billion guilders.

30

By the end of 1941, the Netherlands had already amassed 4.46 billion guilders in debt.

31

A year later that figure was up to 8 billion.

32

28

The exchange rate between the guilder and the reichsmark was set at 1 to 1.33. But the Wehrmacht often exceeded the official limit on occupation costs by more than 20 percent.

29

The demands were devastating in a country whose total state expenditures in 1939 had amounted to only 1.4 billion guilders.

30

By the end of 1941, the Netherlands had already amassed 4.46 billion guilders in debt.

31

A year later that figure was up to 8 billion.

32

Sng>ing Holland in May 1940, the Germans had pursued the idea of creating an economic union that would benefit the Reich, or, in the Nazi euphemism, “effecting an economic merger with Germany.” By April 1,1941, preparations had been completed, and the economic border between the two countries was abolished. In one stroke, occupation and finance authorities opened up the Dutch market to German purchasing power. But the economy was in no condition to cope with added strain. So much money had been spent in the first six months of the occupation that “a national loan of 500 million Dutch guilders” (665 million reichsmarks) had to be issued “to relieve pressure on” the national bank of the Netherlands.

33

Dutch bankers had no choice but to grant the loan, having been forced by their occupiers to redeem “huge sums of reichsmarks” exchanged by German purchasers.

33

Dutch bankers had no choice but to grant the loan, having been forced by their occupiers to redeem “huge sums of reichsmarks” exchanged by German purchasers.

Administrators responsible for keeping the economy of the Netherlands functioning tried to halt the practice of making the Dutch state pay for German purchases that emptied Dutch shelves. They had no success. “It is well known,” the German finance chief in The Hague wrote, “that previously ample reserves” were being bought up “to an enormous extent with RKK certificates.” The goods purchased then “passed across the German border by the usual means under the guard of uniformed German personnel.”

34

Instead of compensating the Netherlands for such hoarding, German economists balanced their accounts with Holland in spring 1941 by inventing fictional occupation costs. The Dutch Finance Department had to write off 400 million reichsmarks in German debt and deliver gold valued at a further 100 million reichsmarks.

35

It was only in 1944, to stave off the complete collapse of the guilder, that the currency border was reestablished.

36

34

Instead of compensating the Netherlands for such hoarding, German economists balanced their accounts with Holland in spring 1941 by inventing fictional occupation costs. The Dutch Finance Department had to write off 400 million reichsmarks in German debt and deliver gold valued at a further 100 million reichsmarks.

35

It was only in 1944, to stave off the complete collapse of the guilder, that the currency border was reestablished.

36

In March 1944, the Economics Ministry calculated that the Netherlands had paid a total of some 8.3 billion reichsmarks in occupation costs.

37

Since German civilians, government agencies, and businesses had purchased goods valued at 4.5 billion reichsmarks, three-fifths of all the putative occupation costs in Holland were directly aimed at enriching Germans.

38

37

Since German civilians, government agencies, and businesses had purchased goods valued at 4.5 billion reichsmarks, three-fifths of all the putative occupation costs in Holland were directly aimed at enriching Germans.

38

To help the Netherlands raise that money, occupation administrators increasingly adapted Dutch business, corporate, and wealth taxes to fit the German model of soaking businesses. In the first few days of the occupation, they imposed a war-profits tax of 10 percent on Dutch businesses, raising it in two increments to 35 percent of net profits within three months.

39

According to one Dutch newspaper, this tax and others would allow the Dutch state (and ultimately Nazi Germany) to claim as much as “83

1/3

percent of all profits.”

40

Unlike in Germany, the wage tax in the Netherlands was raised across the board by 10 percent on July 1, 1942. Occupation authorities also planned to raise the sales tax to fund the Dutch contribution to a vaguely conceived “anti-Bolshevist campaign.” During the spring of 1942, in the interests of social equity, Reich economists discussed “a class-sensitive levy on assets, especially large-scale assets (industry, ‘plutocrats’).” Such a measure, wrote Dutch anti-Semite Rost van Tonningen, “would certainly be very popular” within the Dutch Nazi movement.

41

Once the new taxes had taken effect, the Dutch newspaper Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant calculated, some businesses would be paying 112 percent of their profits.

42

39

According to one Dutch newspaper, this tax and others would allow the Dutch state (and ultimately Nazi Germany) to claim as much as “83

1/3

percent of all profits.”

40

Unlike in Germany, the wage tax in the Netherlands was raised across the board by 10 percent on July 1, 1942. Occupation authorities also planned to raise the sales tax to fund the Dutch contribution to a vaguely conceived “anti-Bolshevist campaign.” During the spring of 1942, in the interests of social equity, Reich economists discussed “a class-sensitive levy on assets, especially large-scale assets (industry, ‘plutocrats’).” Such a measure, wrote Dutch anti-Semite Rost van Tonningen, “would certainly be very popular” within the Dutch Nazi movement.

41

Once the new taxes had taken effect, the Dutch newspaper Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant calculated, some businesses would be paying 112 percent of their profits.

42

Other books

The Buckhorn Brothers Box Set: Sawyer\Morgan\Gabe\Jordan by Lori Foster

The Tudor Throne by Brandy Purdy

Fala Factor by Stuart M. Kaminsky

Death of a Salesperson by Robert Barnard

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

Delinquency Report by Herschel Cozine

Dark Omens by Rosemary Rowe

The Audubon Reader by John James Audubon

Doodlebug Summer by Alison Prince

Teeny Weeny Zucchinis by Judy Delton