History of the Second World War (114 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

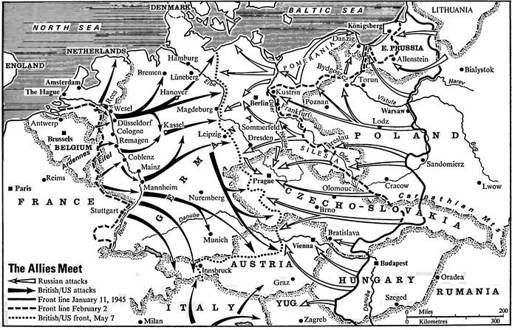

It was the crisis produced by the Russian menace, however, which had led to the Germans’ fateful decision that the defence of the Rhine must be sacrificed to the needs of the Oder, in order to keep the Russians at bay. More important than the actual number of divisions switched from the West to the East was the diversion eastward of the bulk of the reinforcements that could be scraped up to fill the depleted ranks. The way was thus eased for the Anglo-American offensive to reach the Rhine and cross it.

CHAPTER 37 - THE COLLAPSE OF HITLER’S HOLD ON ITALY

While the German winter position looked on the map unpleasantly similar to that of the year before, and almost as formidable, even though 200 miles farther north, there were many favourable factors.* By the end of 1944 the Allies were through the Gothic Line, there was no such naturally strong or well-fortified position ahead, and they were in a much better ‘jumping-off’ position for their spring offensive in 1945. Moreover, there were other important factors that made the Allied armies relatively far more powerful.

* For map, see pp, 524-5.

In March, on the eve of their spring offensive, they comprised seventeen divisions, and now had six Italian combat groups. The Germans had twenty-three divisions, and four so-called Italian divisions which Mussolini had managed to raise in northern Italy since his own rescue by the Germans (these, really, were little larger than combat groups). But any such comparison by number of divisions gives an essentially false picture of the balance. The Allied fighting strength included six independent armoured brigades and four independent infantry brigades — the equivalent of three to four more divisions.

A count of the number of men comes nearer the truth. The Fifth and Eighth Armies totalled some 536,000, besides 70,000 Italians. The Germans totalled 491,000, and 108,000 Italians, but of the Germans 45,000 were police or anti-aircraft personnel. The figures of fighting troops and weapons were a still better way of comparison. For example, when the Eighth Army opened the offensive in April it enjoyed odds of approximately 2 to 1 in fighting troops (57,000 against 29,000), 2 to 1 in artillery (1,220 pieces against 665), and over 3 to 1 in armoured vehicles (1,320 against 400).

In addition, the Allies benefited from the help of some 60,000 partisans, who were producing much confusion behind the German lines and forcing the Germans to divert troops from the front to curb their activities.

Still more important was the Allies’ now absolute command of the air. Their strategic bombing campaign was having such a paralysing effect that German divisions could only have been moved out of Italy to other theatres with great difficulty, even if Hitler had ordered it. Along with it was the Germans’ increasing shortage of fuel for their mechanised and motorised formations, a shortage which was now becoming so acute that they could neither move quickly to close gaps, as they had done previously, nor carry out a delaying ‘manoeuvre in retreat’. But Hitler was more unwilling than ever to sanction any strategic withdrawal even while there was a possibility of attempting it.

The three months’ pause since the close of the Allies’ autumn offensive had brought a great change in the spirit and outlook of their troops. They had seen the arrival of new weapons in abundance — amphibious tanks, ‘Kangaroo’ armoured personnel carriers, ‘Fantails’ (tracked landing vehicles), heavier-gunned Sherman and Churchill tanks, flame-throwing tanks, and ‘tank-dozers’. There was also plenty of new bridging equipment, and huge reserves of ammunition.

On the German side, Field-Marshal Kesselring had returned from convalescence in January, but in March he was called to the Western Front on being appointed to succeed Field-Marshal von Rundstedt as Commander-in-Chief there. Vietinghoff now definitely replaced him as C.-in-C. of Army Group C in Italy. Herr now took command of the German 10th Army which held the eastern part of the front, with the 1st Parachute Corps (of five divisions) and the 76th Panzer Corps (of four). Senger, commanding the 14th Army, held the western part — which was wider, as it included the Bologna sector — with the 51st Mountain Corps (of four divisions) holding the line towards Genoa and the Mediterranean, while the 14th Panzer Corps (of three divisions) covered Bologna. There were only three divisions in Army Group reserve, as two were posted in rear of the Adriatic flank, and two near Genoa, to guard against amphibious landings behind the front. For the time being, also, the three divisions in Army Group reserve were being used to guard against these same contingencies.

On the Allied side, in Mark Clark’s Army Group (entitled the 15th) the right wing, facing the German 10th Army, was formed by the Eighth Army under McCreery, and comprised the British 5th Corps (of four divisions); the Polish Corps (of two divisions); the British 10th Corps, now almost a skeleton consisting of two Italian combat groups, the Jewish Brigade, and the Lovat Scouts; and the British 13th Corps which was really the 10th Indian Division. The 6th Armoured Division was in Army reserve. To the west was the Fifth Army, now commanded by Truscott, which comprised the American 2nd Corps (of four divisions), and 4th Corps (of three divisions), with two more divisions in Army reserve. They included two armoured divisions, the 1st U.S. and the 6th South African.

The aim, and primary problem, of the Allied planners was to overrun and wipe out the German forces before they could escape over the River Po. This could best be achieved by armoured forces in the flat stretch of some thirty miles, between the courses of the lower Reno and the Po. (In the early part of January, when there was a spell of dry weather, the Eighth Army had closed up to the Senio, which runs into the lower Reno near the Adriatic.) It was hoped that the Eighth Army, by seizing the Bastia-Argenta area just west of Lake Comacchio, would be able to open the way into the plain. The Fifth Army was to attack a few days later, thrusting northward near Bologna. The combined thrusts should cut off the Germans’ retreat, and trap them. The Allied offensive was to be launched on April 9.

The Eighth Army’s plan was complex, but ably conceived and designed. Simulated preparations for a landing north of the Po were to keep Vietinghoff looking, and most of his reserve poised, in that direction. To strengthen the impression, Commandos and the 24th Guards Brigade, at the beginning of April, seized the spit of sand separating Lake Comacchio from the sea, and a few days later the Special Boat Service occupied the small islands in that vast inland stretch of water.

The main attack was to be delivered, across the Senio, by the British 5th Corps and the Polish Corps. The former was to break through well up the Senio, hoping to catch the Germans off balance, and there part of it would wheel right against the flank of the Bastia-Argenta corridor (which had come to be called the Argenta Gap) just west of Lake Comacchio, while another part drove north-westward toward the rear of Bologna, to cut off that city from the north. The Poles were to thrust along Route 9, the Via Emilia, more directly towards Bologna. The 56th Division on the right wing (of the 5th Corps) was given the task of storming the Argenta Gap by a combination of direct assault and a flanking manoeuvre by the ‘Fantails’ across Lake Comacchio.

The left wing of the Eighth Army, consisting of the skeletonised 10th and 13th Corps, was to start thrusting northward, past Monte Battaglia, until squeezed out by the converging advance of the Poles and Americans; the 13th would then join 6th Armoured Division in the exploitation of success.

After the preliminary operations on the sandspit and Lake Comacchio had focused Vietinghoff s attention on the coastal sector, a massive bombardment was launched in the afternoon of April 9 by some 800 heavy bombers and 1,000 medium or fighter bombers, while 1,500 guns put down a series of five concentrations, each of forty-two minutes’ duration with ten minute intervals — for which reason they were called ‘false alarm’ bombardments. Then at dusk the infantry advanced, while the Tactical air forces kept the Germans pinned down. The defenders were stunned by this storm of bombs and shells, while the flame-throwing tanks that accompanied the infantry proved a terrifying addition. By the 12th General Keightley’s 5th Corps had crossed the Santerno and was pressing on. Although opposition became stiffer as the Germans recovered from the initial shock, the Bastia Bridge was captured on the 14th, before its demolition was completed. (The ‘Fantails’ had been disappointing on Lake Comacchio, where the water was shallow and the bottom soft, but proved much more effective in the flooded area round the Argenta Gap.) Even so, it was the 18th before the British were right through the Argenta Gap. The Poles met even stiffer opposition from the German 1st Parachute Division before they succeeded in overcoming its outstandingly formidable troops.

The start of the U.S. Fifth Army’s attack was delayed until April 14 by bad weather, particularly bad flying weather for its supporting aircraft — and it had to overcome several remaining mountain ridges before it could get through to the plains and Bologna. On the 15th its progress was aided by the dropping of 2,300 tons of bombs — a record for the campaign. But for two days more the Germans of the 14th Army put up a tough resistance; and it was not until the 17th that the 10th Mountain Division of the U.S. 4th Corps achieved a breakthrough, and raced on towards the vital lateral highway, Route 9. But within two days the whole front was collapsing, and the Americans had reached the outskirts of Bologna, while their exploitation forces were sweeping on to the Po.

Most of Vietinghoff’s forces had been committed to the front line, and he had few reserves — and less fuel — to check an Allied penetration. It was no longer possible to stabilise the front or to extricate his forces, and the only hope of saving them was by retreat — a long retreat. But Hitler had already rejected General Herr’s proposals for an elastic defence, by tactical withdrawals from one river to the next — which might have stultified the British Eighth Army’s offensive. On April 14, just before the American offensive was launched, Vietinghoff appealed for permission to retire to the Po before it was too late. His appeal was rejected, but on the 20th he took the responsibility of ordering such a retreat himself.

By then it was far too late. The Allies’ three armoured divisions, in two sweeping moves, had cut off and surrounded most of the opposing forces. Although many Germans managed to escape by swimming that broad river, they were in no condition to establish a new line. On the 27th the British crossed the Adige and penetrated the Venetian Line covering Venice and Padua.

The Americans, moving still faster, took Verona a day earlier. The day before that, April 25, a general uprising of the partisans took place, and Germans everywhere came under attack from them. All the Alpine passes were blocked by April 28 — the day on which Mussolini and his mistress, Claretta Petacci, were caught and shot by a band of partisans near Lake Como. German troops were now surrendering everywhere, and the Allied pursuit met little opposition anywhere after April 25. By the 29th the New Zealanders reached Venice and by May 2 were at Trieste — where the main concern was not the Germans but the Yugo-Slavs.

Background negotiations for a surrender had, in fact, begun as early as February, initiated by General Karl Wolff, the head of the S.S. in Italy, and handled on the other side by Allen W. Dulles, head of the American O.S.S. (Office of Strategic Services) in Switzerland — using Italian and Swiss intermediaries initially, and then face to face. Wolff’s motives seem to have been a mixture of wishing to avoid further senseless damage in Italy and the desire to repel Communism by aligning with the Western Powers — motives that many Germans shared. Wolff’s importance, besides his control of S.S. policy, lay in the fact that he was in charge of the regions behind the front, and could thus nullify Hitler’s idea of creating an Alpine redoubt for a final stand.

The talks were complicated and delayed on the German side by Vietinghoff being appointed to take over from Kesselring, on the Allied side by Russian demands to participate, and on both sides by the mutual suspicion and caution which accompanies such background negotiations. Although the discussions in March were promising, Karl Wolff’s activities were frozen early in April by Himmler. Thus although Vietinghoff by April 8 was considering a way of surrender, this could not be achieved in time to avert the Allies’ spring offensive.

At a meeting on April 23, however, Vietinghoff and Wolff decided, in agreement, to disregard orders from Berlin for continued resistance, and to negotiate a surrender. By the 25th Wolff had ordered the S.S. not to resist the partisan take-over — and Marshal Graziani was manifesting a desire for surrender on the part of the Italian Fascist forces. At 2 p.m. on April 29, German envoys signed a document providing for an unconditional surrender on May 2 at 12 noon (2 p.m. Italian time). Despite a last minute intervention by Kesselring this duly went into effect on that date — six days before the German surrender in the West. Although military success had assured the Allies of victory, this channel smoothed the way to a quicker ending of the war, thereby curtailing loss of life and destruction.

CHAPTER 38 - THE COLLAPSE OF GERMANY