History of the Second World War (109 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

While Rangoon now lay open to the British, the city had to be reached quickly because of the approach of the monsoon, coupled with the fact that the American transport aircraft were to be withdrawn from Burma and sent to help China at the beginning of June. Rangoon was over 300 miles from Meiktila, and the whole supply system, already stretched, of Slim’s Fourteenth Army would break down, if a South Burma port was not gained before then, to offset the transfer of the American aircraft and provide Slim’s army with an alternative, seaborne, line of supply. So on April 3 Mountbatten took the decision to order ‘Operation Dracula’, for early May, as an insurance in case Slim’s army did not reach Rangoon in time. It was to be carried out by a division from Christison’s corps with a regiment of medium tanks and a Gurkha parachute battalion.

Slim’s plans for the exploiting southward advance from Mandalay and Meiktila were that Messervy’s 4th Corps would drive down the main road and rail route, while Stopford’s 33rd Corps would drive down both banks of the Irrawaddy — the latter depending for supply on inland water transport, while the former continued to have air supply.

The Japanese hoped to hold the Irrawaddy with the troops of their 28th Army arriving from Arakan, and that the remnants of their other two armies would be able to block Messervy. But this proved a vain hope as the remains were not in a fit state to fight. Meanwhile the 5th Division, originally Slim’s reserve, pushed ahead, and by April 14 captured Yamethin, nearly forty miles south of Meiktila. Stopford’s 33rd Corps also started its advance down the Irrawaddy and on May 3 its spearhead division reached Prome, midway to Rangoon, while the Japanese 28th Army was kept bottled on the west bank of the Irrawaddy. Messervy’s spearhead, after a slow start, pushed on still faster by the main road — reaching Toungoo (level with Prome) on April 22, where it headed off the leading remnants of the Japanese 15th Army that were retreating through the Shan Hills. By that time other Japanese remnants were 100 miles behind. A week later Messervy’s spearhead reached Kadok, ninety miles from Toungoo and only seventy from Rangoon. Here it met stiffer resistance, as the Japanese were trying to keep open a link to the east, through Thailand. Within a few days the resistance was overcome, but brief as was the check it sufficed to deprive Messervy’s men of the honour of liberating Rangoon.

For on May 1 ‘Dracula’ had been launched — with a parachute landing at the mouth of the Rangoon River and amphibious landings on both banks. Hearing that the Japanese were already evacuating Rangoon, the whole force re-embarked and moved up the river, entering the city next day. Early on May 6 it met Messervy’s spearhead driving down from Kadok and Pegu. The liberation of Burma was now virtually complete.

Lack of opposition in the later stages of the campaign was mainly due to the Japanese having withdrawn most of their air force, and naval force, to meet the greater menace of the American advance in the Pacific. Against over 800 Allied combat aircraft (650 bombers and 177 fighters) they could only put up fifty obsolescent planes. Moreover, the success of the spirited British advance as a whole had depended on the American transport aircraft which maintained its supplies.

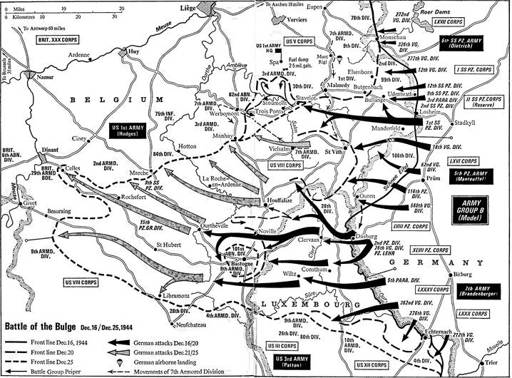

CHAPTER 35 - HITLER’S ARDENNES COUNTERSTROKE

On December 15, 1944, Montgomery wrote a letter to Eisenhower in which he said that he would like to spend Christmas at home before launching the next big offensive on the Rhine. He enclosed an account for £5 for payment of a bet that Eisenhower had made, the year before, that the war would be ended by Christmas, 1944.* That jesting reminder was not very tactful, since only a fortnight earlier — in a letter which ‘made Ike hot under the collar’ — he had pungently criticised Eisenhower’s strategy and its failure to finish off the Germans, and gone on to suggest that Eisenhower should hand over the executive command.†

* Butcher:

My Three Years with Eisenhower,

p. 722.

†

ibid.,

p. 718.

Showing exemplary patience, Eisenhower chose to take Montgomery’s second letter as a joke rather than a jab. Replying on the 16th, he wrote: ‘I still have nine days, and while it seems almost certain that you will have an extra five pounds for Christmas, you will not get it until that day.’

Neither of them, nor the commanders under them, reckoned with possible enemy interference in the pursuit of their offensive plans. On this day Montgomery’s latest estimate of the situation, sent out to his troops in the 21st Army Group, confidently said: ‘The enemy is at present fighting a defensive campaign on all fronts; his situation is such that he cannot stage major offensive operations.’ Bradley, commanding the American forces of the 12th Army Group, held the same view.

But that very morning, December 16, the enemy launched a tremendous offensive which upset the Allied commanders’ plans. The blow was delivered against the front of the U.S. First Army in the Ardennes, a hilly and wooded sector where the troops had been thinned out in order to amass the maximum force along the flatter avenues into Germany. Regarding the Ardennes as unsuitable for their attack, the Allies tended to disregard it as a likely line of enemy attack. Yet it was here that the Germans had chosen to stage the Blitzkrieg four years earlier which had shattered the Allied front in 1940 and produced the collapse of the West. It was strange that the Allied commanders of 1944 should have been so blind to the possibility that Hitler might try to repeat the surprise and its success in the same sector.

The news of the attack was slow to reach the higher headquarters in rear, and they were slower still to recognise its menace. It was late in the afternoon when the news came to S.H.A.E.F., Eisenhower’s headquarters at Versailles, where he and Bradley were discussing the next steps in the American offensive. Bradley frankly says that he regarded the German stroke merely as ‘a spoiling attack’,

*

to hinder his own. Eisenhower says he ‘was immediately convinced that this was no local attack’,† but the significant fact is that the two divisions which he held in S.H.A.E.F. reserve were not alerted for moving to the scene until the evening of the next day, the 17th.

* Bradley:

A Soldier’s Story,

p. 455.

† Eisenhower:

Crusade in Europe,

p. 342.

By that time the thin Ardennes front — where four divisions (of General Middleton’s 8th Corps) were holding an eighty-mile stretch — had been burst wide open by the assault of twenty German divisions, of which seven were armoured, mustering nearly a thousand tanks and armoured assault guns. Bradley, on getting back to his Tactical H.Q. at Luxembourg, found his puzzled Chief of Staff brooding over the map in the war room, and exclaimed: ‘Where in hell has this sonuvabitch gotten all his strength?’‡ The situation was worse than his H.Q. yet knew. Panzer spearheads had already penetrated up to twenty miles, and one of them had reached Stavelot. Until then, the Commander of the U.S. First Army, Hodges, had also discounted the German thrust — and at first insisted on pressing on with his own offensive moves against the Roer Dams farther north. It was only on the morning of the 18th that he awoke to the seriousness of the menace on finding that the Germans had passed through Stavelot and were close to his own headquarters at Spa — which was hurriedly moved back to a safer area.

‡ Bradley:

A Soldier’s Story,

p. 466.

The Higher Command’s slowness in grasping the situation was partly due to the slowness with which information came back to them. This in turn was largely due to the way that German commandos, infiltrating in disguise through the broken front, cut many of the telephone wires running back from the front, and also spread confusion.

But that does not explain the Higher Command’s seeming blindness to the possibility of a German counterstroke in the Ardennes. Allied Intelligence had known since October that the panzer divisions were being withdrawn from the fighting line to refit for fresh action, and that part had been formed into a new 6th S.S. Panzer Army. By early December it was reported that the H.Q. of the 5th Panzer Army, after being relieved in the Roer sector west of Cologne, had shifted south to Coblenz. Moreover tank formations had been spotted moving towards the Ardennes, and newly formed infantry divisions had appeared in the line there. Then on December 12 and 13 came reports that two specially famous ‘Blitz’ divisions, the Grossdeutschland and the 116th Panzer, had arrived in this ‘quiet’ sector, and on the 14th that bridging equipment was being hauled up to the River Our which covered the southern half of the American front in the Ardennes. As early as December 4 a German soldier captured on this sector had revealed that a big attack was being prepared there, and his account was confirmed by many others taken in the days that followed. They also stated that the attack was due in the week before Christmas.

Why did these increasingly significant signs receive such scant attention? The Intelligence head of the First Army was not on very good terms with the Operational head, nor with the Intelligence head of the Army Group, and was also regarded as an alarmist inclined to cry ‘Wolf’.* Moreover, even he failed to draw clear deductions from the facts he had gathered, while the imminently threatened 8th Corps formulated the perilously mistaken conclusion that the change-round of divisions on its front was merely the enemy’s way of giving the new ones front-line experience prior to use elsewhere, and ‘indicates his desire to have this sector of the front remain quiet and inactive’.

* Bradley:

A Soldier’s Story,

p. 464.

But besides lack of a clear picture of the strength of the attack from Intelligence, the miscalculation of the Allied Higher Commanders seems to have been due to four factors. They had been on the offensive so long that they could hardly imagine the enemy taking the initiative. They were so imbued with the military idea that ‘attack is the best defence’ as to become dangerously sure that the enemy could not hit back effectively so long as they continued their own attack. They reckoned that even if the enemy attempted a counterstroke it would be only in direct reply to their own direct advance towards Cologne and the industrial centres of the Ruhr. They counted all the more on such orthodoxy and caution on the enemy’s side since Hitler had reappointed the veteran Field-Marshal Rundstedt, now in his seventieth year, as Commander-in-Chief in the West.

They proved wrong in all these respects, and the misleading effect of the first three was multiplied by the error of the last assumption. For Rundstedt had nothing to do with the counterstroke except in a nominal way, although the Allies called it ‘the Rundstedt offensive’ — much to his annoyance then and later, since he not only disagreed with this offensive but washed his hands of it, leaving his subordinates to conduct it as best they could, with his H.Q. acting merely as a post office for Hitler’s instructions.

The idea, the decision, and the strategic plan were entirely Hitler’s own. It was a brilliant concept and might have proved a brilliant success

if

he had still possessed sufficient resources, as well as forces, to ensure it a reasonable chance of succeeding in its big aims. The sensational opening success was due partly to new tactics developed by the young General Hasso von Manteuffel — whom Hitler had recently promoted from a division to command an army, at forty-seven. But it was due also to the widely paralysing effect of a half-fulfilled brainwave of Hitler’s — aimed to open the way to victory over the Allied armies, with their millions of men, by the audacious use of a few hundred men. For its execution he employed another of his discoveries, the thirty-six-year old Otto Skorzeny, whom he had sent the year before on a glider-borne raid to rescue Mussolini from a mountain-top prison.

Hitler’s latest brain-wave was given the codename ‘Operation Greif’ — the German word for that mythical creature, the Griffin. It was aptly named, for its greatest effect would be in creating a gigantic and alarming hoax behind the Allied lines.

As planned, however, it was a two-wave design that formed a modern version in strategy of the ‘Trojan Horse’ stratagem of Homeric legend. In the first wave a company of English-speaking commando troops, wearing American field jackets over their German uniforms and riding in American jeeps, was to race ahead in little packets as soon as the front was pierced — to cut telephone wires, turn sign-posts to misdirect the defender’s reserves, hang red ribbons to suggest that roads were mined, and create confusion in any other way they could. Second, a whole panzer brigade in American ‘dress’ was to drive through and seize the bridges over the Meuse.

This second wave never got going. The Army Group staff failed to provide more than a fraction of the American tanks and trucks required, and the balance had to be made up with camouflaged German vehicles. That thin disguise entailed caution, and no clean breakthrough was made on the northern sector where this brigade was waiting, so its advance was postponed, and eventually abandoned.