High Heat (13 page)

Authors: Tim Wendel

Such quality pitching was too much for the lords of baseball. They wanted runs and higher scores. So after the 1968 season, they shrank the strike zone. It had been from the batter's shoulders to his knees. Now it was from the armpits to the top of the knees, and the way some umpires began to call the game it was destined to shrink even further. In addition, the mound was lowered five inches. Carl Yastrzemski would later say that this last adjustment favored sinkerball pitchers and put the power pitchers, those who threw a hard fastball and curveball, at a real disadvantage.

“I know for a fact that pitchers love throwing on a high mound more than they do a lower one,” legendary pitching coach Leo Mazzone wrote in his

Tales from the Mound

. “They lowered the mound in '69 because of the domination of pitching, because of Bob Gibson and Don Drysdale. Now I think you have to have an equalizer of some sort on the other side. It's favored the offense over the last few years.”

Tales from the Mound

. “They lowered the mound in '69 because of the domination of pitching, because of Bob Gibson and Don Drysdale. Now I think you have to have an equalizer of some sort on the other side. It's favored the offense over the last few years.”

Although Ryan won his first game at the major-league level in 1968, that was little more than a footnote in “the Year of the Pitcher.” By 1969, Ryan was mostly pitching out of the bullpen. Seaver and Koosman were the staff aces as the Mets came from 9 ½ games back to overtake the Chicago Cubs and capture the National League East Division and later the pennant. New York mostly did it with pitching, putting up 16 shutouts. Ryan chipped in with six victories, none of them a shutout. In the year of the “Amazin' Mets,” New York could do little wrong. The Mets even won a game in mid-September when Steve Carlton struck out a record 19 batters.

Ryan came out of the bullpen to win a game in the National League Championship Series against the Braves. Some in the media expected that would earn him a start in the World Series against the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles. But Ryan didn't see any action until Game Three at Shea Stadium. The Mets were ahead 4â0 when starter Gary Gentry loaded the bases with two out in the seventh inning. That's when manager Gil Hodges signaled for Ryan.

Anxious to get the ball over and not walk in a run, Ryan threw a fastball to the Orioles' Paul Blair. As soon as the ball left Blair's bat, Ryan knew it was trouble. It was deep, heading for the fence in right-center field. But Mets outfielder Tommie Agee somehow tracked the ball down, sliding onto one knee to make the grab.

“It was an amazing catch, a catch that sent a charge through all the fans at Shea,” Ryan later said. “I felt like applauding, too. Agee had gotten me off the hook, and I [had] gotten away with a bad pitch.”

After that bit of luck, Ryan pitched into the ninth inning, when he loaded the bases with two out. Even though the Mets still led 5â0, Hodges nearly took Ryan out. Knowing he was on a short leash, Ryan threw two fastballs by Blair again and then struck out the Orioles' outfielder with an unexpected curveball. Ryan got the save and the Mets went on to upset Baltimore for the title.

“This will be an important spring for Nolan,” Hodges told reporters in spring training. “He's now on the threshold of becoming not only a good pitcher but a great one.”

Yet the Mets weren't as patient as their manager. In 1970, Ryan was as frustratingly inconsistent as ever. He went 7â11 that year and 10â14 the following one as he was also required to travel to four different military bases to satisfy his U.S. Army Reserve obligations. In fact, Ryan was becoming so disillusioned with baseball in general that he again talked seriously with Ruth about quitting the game, returning to Alvin, and going into a new line of work.

After the 1971 season, Ryan returned home to Alvin. His first child, Reid, had just been born. In his autobiography, Ryan remembered that he was heading out the door to class at Alvin Junior College when the phone rang. It was the Mets with news that he had been traded to the California Angels in the American League along with outfielder Leroy Stanton and prospects Don Rose and Francisco Estrada for infielder Jim Fregosi. Fregosi had batted .233, with five home runs and 33 RBI in 107 games the year before.

In the subsequent newspapers stories, Hodges told the press he had approved the trade. His patience had run out as well. The Mets' manager added that Ryan, among all the young pitchers on his team, was the one he would miss the least.

The Stride

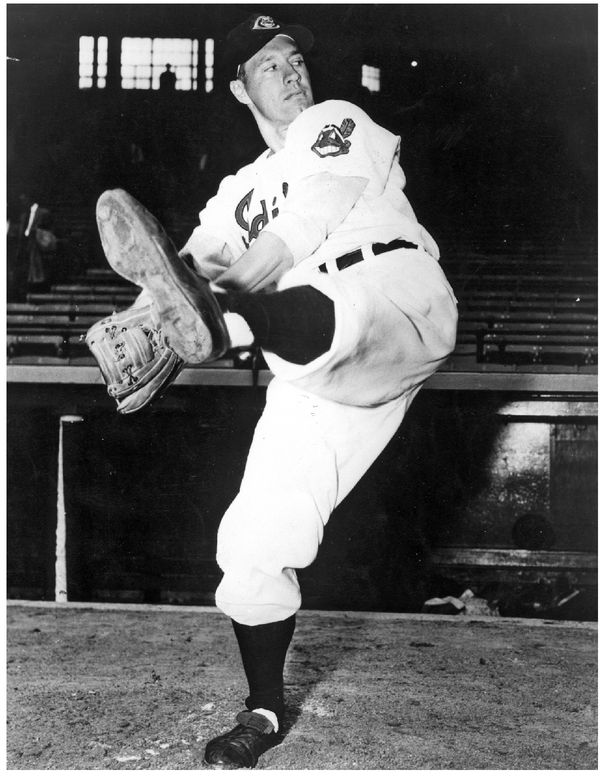

Bob Feller

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY

I got brains. But you got talent. Your god damn left arm is worth a million dollars a year. All my limbs put together are worth seven cents a poundâand that's for science and dog meat.

âCRASH DAVIS,

BULL DURHAM

BULL DURHAM

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

A

top Hollywood producer once told me that the trick to making a memorable movie, a real blockbuster, is to have “two or three scenes people still remember days after they walk out of the theater.”

top Hollywood producer once told me that the trick to making a memorable movie, a real blockbuster, is to have “two or three scenes people still remember days after they walk out of the theater.”

“Give me those,” he said, “and I can do the rest. I'll fill in the backstory and figure out the best places to shoot it, get a star or two on board. But if I don't have those two or three big scenes, it's tough to really make it work.”

Maybe that's why there are so many lousy movies out there these days. Too often the so-called big scenes are ginned up with digital effects and Dolby surround-sound and offer little in terms of character or story. When we stumble upon a movie that offers a healthy slice of both, it often sticks with us far longer than anybody expected.

That's what runs through my mind as I enter the front lobby of the new Durham Bulls ballpark. I'm in town to catch up with left-hander David Price, who was sent down to Triple-A after spring training to work on his slider and changeup. What was repeated by everyone in the Tampa Bay Rays' organization was that Price possessed one of the top fastballs in the game but needed to work on his overall consistency.

Down on the field, the Bulls are caught up in team photo day and Price is posing with his minor-league teammates. Even though the imposing left-hander is expected to rejoin the parent club sometime this season, action photos of him adorn the cover of the Bulls' 2009 media guide. With some time to kill, I head for the team gift store. If in doubt, squander the time by buying trinkets, right? It's there I'm greeted by a poster of Kevin Costner, aka Crash Davis himself.

Costner has starred in his share of baseball movies:

For Love of the Game

and

Field of Dreams

. But the one flick that fans and players both agree Hollywood got right, that had more than its share of boffo scenes that would make any producer sleep like a baby at night, was

Bull Durham

. Filmed at the old Durham ballpark in 1987, its memorable moments include the scene where the team gathers on the mound to talk wedding gifts rather than game strategy. Or the quick tutorial about sports clichés aboard the team bus. Or when the wild fireballer beans the Bulls mascot on purpose.

For Love of the Game

and

Field of Dreams

. But the one flick that fans and players both agree Hollywood got right, that had more than its share of boffo scenes that would make any producer sleep like a baby at night, was

Bull Durham

. Filmed at the old Durham ballpark in 1987, its memorable moments include the scene where the team gathers on the mound to talk wedding gifts rather than game strategy. Or the quick tutorial about sports clichés aboard the team bus. Or when the wild fireballer beans the Bulls mascot on purpose.

The film's big moments often revolve around how the game is a curse to some and a gift to only a selectâdare we say, undeservingâfew. In

Bull Durham,

Crash Davis portrays baseball's version of Shakespeare's everyman. The guy who knows as much about baseball as anybody under the sun but will never make the majors for longer than a cup of coffee. His foil is the hard-throwing pitcher Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh. Played by Tim Robbins, the young fireballer doesn't have a clue about the game or life in general. Yet he has an arm capable of throwing lightning bolts. To heighten the plot line, both ballplayers are determined to win the affections of the lovely Susan Sarandon.

Bull Durham,

Crash Davis portrays baseball's version of Shakespeare's everyman. The guy who knows as much about baseball as anybody under the sun but will never make the majors for longer than a cup of coffee. His foil is the hard-throwing pitcher Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh. Played by Tim Robbins, the young fireballer doesn't have a clue about the game or life in general. Yet he has an arm capable of throwing lightning bolts. To heighten the plot line, both ballplayers are determined to win the affections of the lovely Susan Sarandon.

The movie poster in the Bulls' souvenir shop details Crash's philosophy of life: “I believe that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. I believe that there outta be a constitutional amendment outlawing Astroturf and the designated hitter. I believe in the âsweet spot,' voting every election, soft core pornography, chocolate chip cookies, opening your presents on Christmas morning rather than Christmas Eve, and I believe in low, slow, deep, soft, wet kisses that last for seven days.” Perhaps more than any one scene, it's Crash, himself,

that's so memorable. But I think the reason why so many love the movie, and identify with Crash, has more to do with an acknowledgment that life, at some basic level, isn't fair. If it were, the more deserving Crash would be the one bestowed with the stupendous fastball instead of the often clueless Nuke.

that's so memorable. But I think the reason why so many love the movie, and identify with Crash, has more to do with an acknowledgment that life, at some basic level, isn't fair. If it were, the more deserving Crash would be the one bestowed with the stupendous fastball instead of the often clueless Nuke.

Bull Durham

was written and directed by Ron Shelton. He drove to minor-league ballparks throughout the South, determining where to film. He kept coming back to the old stadium in Durham, which still stands on the north side of town.

was written and directed by Ron Shelton. He drove to minor-league ballparks throughout the South, determining where to film. He kept coming back to the old stadium in Durham, which still stands on the north side of town.

“I loved that it was located among abandoned tobacco warehouses and on the edge of an abandoned downtown and in the middle of a residential neighborhood where people could walk,” he once told the Associated Press. “In the '80s, minor-league baseball wasn't happening. Now, of course, it's huge business. I thought that it had a feel of the kind of baseball I lovedâsmall-town, intimate, the players could talk to the fans and back and forth.”

Shelton had spent several seasons playing in the Baltimore Orioles' minor-league system, beginning to play professional ball about the time Steve Dalkowski was falling out of the game. During that time Shelton heard the stories about a real-life Nuke, the unfortunate pitcher who never found a catcher like Crash Davis to steer him straight.

“It was a groundskeeper in Stockton who first told me about Steve Dalkowski, the fastest pitcher of all time,” Shelton wrote years later in the

Los Angeles Times

. “âDalko once threw the ball through the wood boards of the right field fence,' he said. The groundskeeper studied the broken boards, maintained like a shrine, and the Dalkowski stories started flowing. In minor-league ballparks all over the country, they still talk about the hardest thrower of them all.”

Los Angeles Times

. “âDalko once threw the ball through the wood boards of the right field fence,' he said. The groundskeeper studied the broken boards, maintained like a shrine, and the Dalkowski stories started flowing. In minor-league ballparks all over the country, they still talk about the hardest thrower of them all.”

Those tall tales included Dalkowski being so wild one night that his pitch hit the announcer's booth. Dalkowski scholar John-William Greenbaum tells me that this story “is patently false.” But that didn't keep Shelton from including it in his movie. An incident where a Dalkowski pitch hit a poor fan standing in line for a hotdog became Nuke plunking the Durham Bulls mascot at Crash's urging. Perhaps the ultimate tribute by Shelton to Dalkowski was Nuke's statistical

line: 170 innings pitched, 262 strikeouts and 262 walks. In real life, Dalkowski did just that for the Stockton Ports in 1960.

line: 170 innings pitched, 262 strikeouts and 262 walks. In real life, Dalkowski did just that for the Stockton Ports in 1960.

Â

Â

A

s the 2009 season got under way, many in the baseball world had heard of David Price. Most wondered why he was in Triple-A Durham instead of Tampa Bay, pitching for the big-league ballclub. Such talk only grew louder when the Rays stumbled out of the gate, going 8â14 in the first month of the new season. Still, the team stuck to its plan of building up Price's innings in the minors. The powers that be had deemed he needed to work on his control and pitch repertoire.

s the 2009 season got under way, many in the baseball world had heard of David Price. Most wondered why he was in Triple-A Durham instead of Tampa Bay, pitching for the big-league ballclub. Such talk only grew louder when the Rays stumbled out of the gate, going 8â14 in the first month of the new season. Still, the team stuck to its plan of building up Price's innings in the minors. The powers that be had deemed he needed to work on his control and pitch repertoire.

“Just because things aren't going the way we thought they would right now, doesn't mean you blow everything up and start all over,” Rays manager Joe Maddon says. “We tend to not do that.”

Indeed, the Rays stayed amazingly even-keel even though they play in the American League East, arguably the toughest division in baseball. One in which the Toronto Blue Jays and Boston Red Sox were off to good starts in 2009 and the New York Yankees reveled in the hubbub of moving into their new majestic $1.5-billion ballpark. Down in Durham, Price did his best to focus on the challenge at hand.

“I know what I need to do,” he says. “I cannot control when I get called up. So, you make the best of it, you know. You tell yourself to just keep working, getting better.”

As Price spoke, he gazed out on the field, watching the grounds crew water down the mound and drag the infield one last time. The PA system carried the local sports talk show until the topic turned to steroids and Alex Rodriguez's return to the big leagues. Then somebody changed the station to classic rock. The gates were due to open soon, with a crowd of 6,000-plus expected. That's a decent attendance figure for a weekday night in the minors. But, of course, it's a far cry from the big leagues.

During the games, when he's not pitching, Price says that his mind can wander. He'll sneak trips into the clubhouse, where the MLB Network, the new 24-hour channel broadcasting all things baseball, is

often on. Tonight the Rays are in Fenway Park, playing the Red Sox. Price knows as well as anybody that several members of Tampa Bay's rotationâAndrew Sonnanstine, James Shields, and Jeff Niemannâhave struggled at times, and that if they continue to do so he could be just the guy to bolster the pitching staff. He surfs the Net daily. He knows what they're saying in Tampaâhow he could be the answer to a lot of problems with the big-league ballclub.

often on. Tonight the Rays are in Fenway Park, playing the Red Sox. Price knows as well as anybody that several members of Tampa Bay's rotationâAndrew Sonnanstine, James Shields, and Jeff Niemannâhave struggled at times, and that if they continue to do so he could be just the guy to bolster the pitching staff. He surfs the Net daily. He knows what they're saying in Tampaâhow he could be the answer to a lot of problems with the big-league ballclub.

Other books

Kentucky Rain by Jan Scarbrough

In It to Win It by Morgan Kearns

Revealing Kia by Airicka Phoenix

Don't I Know You? by Marni Jackson

Redemption by Sherrilyn Kenyon

Lifesong by Erin Lark

Going For It by Liz Matis

Judah the Pious by Francine Prose

Promise of Joy by Allen Drury

Alpha A Paranormal Encounter by Sophia Severn