High Heat (8 page)

Authors: Tim Wendel

“[Harris] had at his disposal not merely the best pitcher on the team, or even the best in the leagueâhe had The Greatest Pitcher in the History of Baseball to call upon,” Thomas wrote in the biography of his grandfather. The capital letters are his.

Visibly nervous, Johnson walked out to pitch the top of the ninth inning. Even though some later remembered that his face was ashen, his warm-up throws were soon cracking Herold “Muddy” Ruel's catcher's mitt. As the warm-up continued, a buzz began to spread through the standsâthe Big Train's fastball was back.

Or was it?

After Johnson got one out, Frankie Frisch scorched his offering into right-center field. Only a great throw by Earl McNeely held him to three bases. After a conference at the mound, the Senators decided to walk Ross Youngs, a left-handed hitter, bringing up RBI champion Kelly. Washington was playing the averages here, as the right-handed Kelly was only two for nine against Johnson. The gambit worked as Kelly went down on three fastballs. That made two outs, with Emil “Irish” Meusel coming up. Johnson got out of the inning when Meusel hit a grounder to third and 5-foot-8 Joe Judge stretched to snag the throw at first base.

Back and forth the teams went in extra innings, with the hometown crowd cheering wildly when the Senators were at bat and becoming quietly apprehensive when Johnson was on the mound. Through it all, Johnson pitched four innings of scoreless ball. “I'd settled down to believe, by then, that maybe this was my day,” Johnson later said.

In the bottom of the 12th inning, Washington's glorious ending began innocently enough. With one out, Ruel, who was having a miserable series, appeared to pop up in foul territory. Giants catcher Hank Gowdy drifted back to make the catch, tossed off his mask, only to trip over it a few steps later. Given a second chance, Ruel doubled to left. That brought up Johnson. He hit the first pitch hard and when it was bobbled, he was safe at first.

Next up was Earl McNeely, and with men at first and second base he hit what appeared to be a tailor-made double play ball directly at third baseman Freddy Lindstrom. That would have been enough to end the inning.

For a moment, the ball appeared headed for Lindstrom's glove. On the last bounce, though, it seemed to hit a pebble or was levitated by the baseball gods themselves, perhaps a nod to Johnson. Whatever the reason, it bounded over Lindstrom's head and rolled into left field. Ruel rounded third and chugged for home, and the Senators and their longtime fireballer had at last won the championship.

As the fans poured onto the field, Johnson stood at second base, tears in his eyes.

Up in the press box, Christy Mathewson watched in disbelief. His body ravaged from being gassed during World War I, it would be the last World Series Mathewson would ever witness. “It was the greatest World Series game ever played, I'm sure,” Mathewson said. “I'm inclined to think, indeed, that it was the most exciting game ever played under any circumstances.”

Today, a monument of bronze and granite stands in tribute to the Big Train at Walter Johnson High School, located around the corner from Shirley Povich Field, where Bruce Adams's ballclub plays. The impressive slab, which shows Johnson pitching along with a list of

accomplishmentsâgames won (414), shutouts (113), strikeouts (3,497), and scoreless consecutive innings (56)âwas unveiled at Griffith Stadium in 1947, less than a year after his death. President Truman presided at the event, where he called Johnson “the greatest ballplayer who ever lived.”

accomplishmentsâgames won (414), shutouts (113), strikeouts (3,497), and scoreless consecutive innings (56)âwas unveiled at Griffith Stadium in 1947, less than a year after his death. President Truman presided at the event, where he called Johnson “the greatest ballplayer who ever lived.”

Every year the student body celebrates Johnson's birthday (November 6, 1887) with sheet cake. When the high school team competes on the television show

It's Academic,

the squad often brings along a baseball talisman for good luck.

It's Academic,

the squad often brings along a baseball talisman for good luck.

The Washington Nationals, the new professional team in town, were interested in moving Johnson's monument permanently to the new ballpark in southeast Washington. But the high school eventually turned down the request. Instead, the Nationals commissioned a statue of Johnson, along with ones of Frank Howard and Josh Gibson, which were unveiled outside before Opening Day 2009.

By retaining the monument, Principal Christopher Garran hopes that the memory of the Big Train will inspire future classes at Walter Johnson High. That they will even touch the slab for luck on the way to their games.

“We could have given it to the Nats, for the new ballpark,” Garran says, “but it just didn't seem right in a way. After all, Walter Johnson is the person our school is named after. Once you learn a little about him, you realize what a hero the Big Train was.”

Â

Â

B

eing able to throw a baseball at speeds of 100 miles per hour or greater is certainly a gift. But during the careers of almost every fireballerâJohnson, Feller, Nolan Ryan, Steve Dalkowkiâthere comes a time when this gift will ultimately be remembered as a blessing or a curse. For Johnson, the moment was likely the 1924 World Series. For Feller, it came 14 years later, on the last day of the 1938 season.

eing able to throw a baseball at speeds of 100 miles per hour or greater is certainly a gift. But during the careers of almost every fireballerâJohnson, Feller, Nolan Ryan, Steve Dalkowkiâthere comes a time when this gift will ultimately be remembered as a blessing or a curse. For Johnson, the moment was likely the 1924 World Series. For Feller, it came 14 years later, on the last day of the 1938 season.

The Indians hosted the Detroit Tigers in a doubleheader on October 2, a sunny day that held a hint of the long winter to follow. Hank Greenberg, the Tigers' All-Star first baseman, came into the

game two home runs shy of Babe Ruth's 60 home runs in one season. At that point in history, it was baseball's most recognizable mark.

game two home runs shy of Babe Ruth's 60 home runs in one season. At that point in history, it was baseball's most recognizable mark.

Many of the Indians vowed that Greenberg wouldn't break the Babe's record on their watch. Several of the veteran ballplayers, especially Hal Trosky, fondly remembered Ruth. Out of loyalty to the Babe, they didn't want to see Greenberg break the 60-home-run mark.

But there was also an undercurrent of prejudice, even religious zeal, that day in Cleveland. Greenberg was the first Jewish superstar in the national pastime. Across the Atlantic, Hitler was making religion a device for division and quickly gaining political power in Germany. Into this cauldron of escalating allegiances and pursuits of all-time individual records stepped Feller. He had been named to be the starting pitcher in the first game of the doubleheader. More than 27,000 fans attended the game to bid the Indians adieu for another season and to see if Greenberg could catch the Babe. Instead they were treated to a different record performance.

The Indians decided they would pitch to Greenberg. No intentional walks, even with men in scoring position. Going against Feller, the great Tigers first baseman, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame 18 years later, went 1-for-4. His lone hit in the first game was a double. He had better success in the second game with three hits, but they were all singles. He finished the day still with 58 home runs. The Babe's record would be safe until Roger Maris broke it in 1961.

In that first game, Greenberg was one of the few Tigers to have any success against Feller. The Indians' hurler would finish the 1938 season with 240 strikeouts and a modern major-league record 208 walks. But on this day, the elements of his game came together, becoming a template that would guide him to 20-plus victory seasons in the next three years, before World War II sent him overseas.

At the time, the major-league record for strikeouts in a nine-inning game was 17, set by another fireballer, Dizzy Dean. But early on against the Tigers, many in the crowd sensed that Feller's stuff, especially his fastball, had never been better.

“It was one of those days when everything feels perfect,” Feller says, “your arm, your coordination, your concentration, everything. There was drama in the air because of Greenberg's attempt to break Ruth's record, and the excitement became even greater when my strikeouts started to add up.”

After striking out rookie second baseman Ben McCoy in the first inning, Feller struck out the side in the second, third, and fourth innings. He picked up two more Ks in the fifth, two more in the sixth, and one each in the seventh and eighth, so by the time the ninth inning rolled around the crowd was on its feet, realizing that Feller was on a record pace.

That's when this 19-year-old phenom got Pete Fox for his 17th strikeout of the game. Feller's walk of Detroit catcher Birdie Tebbetts then brought up Chet Laabs. The odds were definitely working against Feller now. He had already struck out Laabs four times in the game. The next season Laabs would be traded to the St. Louis Browns, where he would lead the league in pinch hits. Just the type of batter the baseball gods will often befriend. The kind of future journeyman perfectly capable of derailing history.

But Feller quickly ran two fastballs past Laabs. When he first entered the big leagues, Feller was criticized for going away from his best pitchâthat is, his fastballâwith the game on the line. Early in his career, he had given up a game-winning home run to Joe DiMaggio when he went with a breaking pitch instead of his high heat. Afterward his father told him to stay with the fastball the next time he was in a tight situation.

So, on this day, with the hometown crowd behind him, Feller didn't make the same mistake again. He went with another fastball low at Laabs's knees. Home plate umpire Cal Hubbard decided it caught enough of the inside corner of the plate and called Laabs out on strikes. Feller had his 18-strikeout game and a career destined to one day land him in the Hall of Fame.

“I was lucky, too, because I threw in the American League,” Feller tells the crowd in the conference room at Jacobs Field.

“I really believe that because the ball in the American League had blue seams. That's why I only use a pen with blue ink to this day. But I believe the American League model, with those blue stitches, was aerodynamically better for speed, for guys like me. Some of you may scoff at that, but I always believed it.”

“I really believe that because the ball in the American League had blue seams. That's why I only use a pen with blue ink to this day. But I believe the American League model, with those blue stitches, was aerodynamically better for speed, for guys like me. Some of you may scoff at that, but I always believed it.”

Whether it was the blue seams or his farm upbringing that so closely paralleled Johnson's, Feller retained his high-octane fastball. He returned from four years in the U.S. Navy in World War II, the longest tenure of any big-league superstar, to strike out 348 in 1946, one away from Rube Waddell's modern record. Yet the following season, his left leg came down awkwardly during that high leg kick of his at Philadelphia's Shibe Park, ironically on Friday the 13th. He injured a muscle in his back, and he claims his fastball was never the same. That didn't stop Feller from being a winner at the major-league level, though. From 1948 to 1956, he won 108 games and helped lead the Cleveland Indians to their last World Series championship in 1948.

“Three days before he pitched I would start thinking about Robert Feller, Bob Feller,” Ted Williams once said. “I'd sit in my room thinking about him all the time. God, I loved it . . . Allie Reynolds of the Yankees was tough, and I might think about him for 24 hours before a game, but Robert Feller; I'd think about him for three days.”

Â

Â

T

he only way the motorcycle test worked was by Feller hitting the cantaloupe-sized target with his first and only pitch. “I did it on the first try and you know something?” he tells the assembled crowd in Cleveland. “I'm as proud of that as anything I ever did in my career.”

he only way the motorcycle test worked was by Feller hitting the cantaloupe-sized target with his first and only pitch. “I did it on the first try and you know something?” he tells the assembled crowd in Cleveland. “I'm as proud of that as anything I ever did in my career.”

That includes three no-hitters and a dozen one-hitters.

At one level, the motorcycle test was inconsequential. There is no mention of it alongside his records in the Hall of Fame or

The Baseball Encyclopedia

. By now we've watched footage of the motorcycle test many times through, the room falling silent every time. Even though Bob DiBiasio, the ballclub's vice president for public relations,

has seen the film many times before, he cannot resist watching it again.

The Baseball Encyclopedia

. By now we've watched footage of the motorcycle test many times through, the room falling silent every time. Even though Bob DiBiasio, the ballclub's vice president for public relations,

has seen the film many times before, he cannot resist watching it again.

“Now that's old school,” he says. “You don't see a ball thrown like that anymore. It's remarkable.”

Feller smiles and lets the film play through for a final time. Previously, he has stopped the tape here and rewound it, but now he lets it continue to roll. The motorcycle footage ends, sharp and ragged like the conclusion of a silent movie, to be suddenly replaced by the old comedy team of Abbott and Costello doing their famous routine “Who's on First?”

As the room breaks into laughter, Feller leans over and tells me that he often puts the two segments together. For decades, from the Little League annual dinners to his speaking engagements aboard cruise ships, he's rolled the two out as a twin bill, his own doubleheader.

“It makes sense, in an odd way,” he says. “Me throwing against a motorcycle and then these two funnymen. I don't know which one I get a bigger chuckle out of these days.”

The Pivot

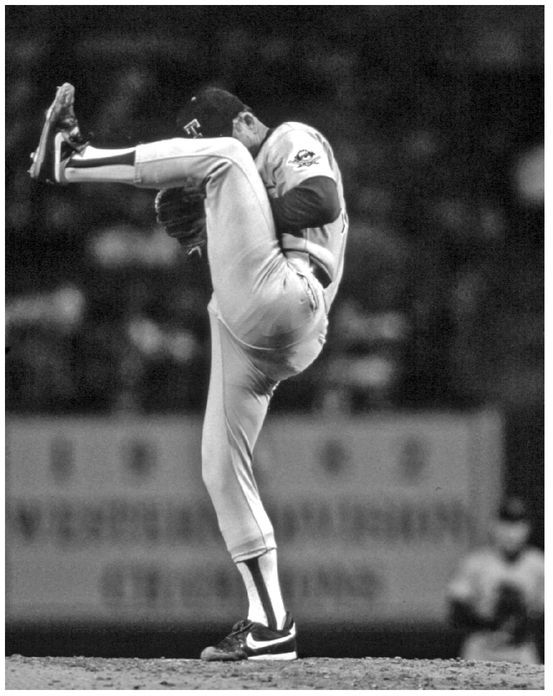

Nolan Ryan

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY

We come into this world head first and go out feet first; in between, it is all a matter of balance.

âPAUL BOESE

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

T

he 2009 spring training season was the strangest in some time. Steroids were back in the news as the Yankees' Alex Rodriguez, arguably the best player in the game, admitted to performance-enhancing drugs after being outed in a

Sports Illustrated

cover story. In Florida and Arizona, where enthusiastic crowds gathered to watch their favorite major-league ballclubs get into shape, nobody was quite sure where the top players were. After a week or so with their regular-season teams, many of the best-known stars headed elsewhere to train with squads of their fellow countrymen in preparation for the second World Baseball Classic.

he 2009 spring training season was the strangest in some time. Steroids were back in the news as the Yankees' Alex Rodriguez, arguably the best player in the game, admitted to performance-enhancing drugs after being outed in a

Sports Illustrated

cover story. In Florida and Arizona, where enthusiastic crowds gathered to watch their favorite major-league ballclubs get into shape, nobody was quite sure where the top players were. After a week or so with their regular-season teams, many of the best-known stars headed elsewhere to train with squads of their fellow countrymen in preparation for the second World Baseball Classic.

Other books

Force of Nature by Logan, Sydney

The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch

El Umbral del Poder by Margaret Weis & Tracy Hickman

Longarm 243: Longarm and the Debt of Honor by Evans, Tabor

Travesty by John Hawkes

Obsession: Tales of Irresistible Desire by Paula Guran

Born of Shadows by Sherrilyn Kenyon

Grace Interrupted by Hyzy, Julie

Hall of Infamy by Amanita Virosa

Belonging Part III by J. S. Wilder