Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (23 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

Nazca Lines are located close to watercourses, and in many cases seem to follow the direction of the water. Perhaps

part of the function of the lines was to

point to sources of water?

An idea linked to the religious road

theory was proposed by English explorer and filmmaker Tony Morrison.

Morrison carried out extensive research into the ancient folkways of the

Nazca people and found a tradition of

wayside shrines, often merely a pile of

stones, linked together by straight

lines. Morrison believes that the Nazca

lines represent huge versions of these

folkways along which Shamans would

walk on a "voyage of the soul." Shamans

were members of a tribe who acted as

mediums between the visible world and

the invisible spirit world, and were

prominent in most Native American

societies. Perhaps when the Shamans

walked along the lines of the animal

glyphs, they were attempting to put

themselves in touch with potent animal spirits. On behalf of the tribe, the

Shaman would (in an altered state of

consciousness) make personal contact

with the supernatural powers contained within the glyphs and attempt

to utilize their energy, perhaps to bring

rainfall, or perhaps for a purpose we

could never even begin to understand.

The experience of Shamans usually involved some sort of flight, so Erich von

Daniken may in fact have been partly

right when he proposed that the glyphs

were designed to be seen from the air.

However, there is no need for alien visitors; the motivation for the creation of

the Nazca lines was connected with the

mountain spirits of the Nazcans high

up in the misty Andes, their gods dwelling in the sky, and the mystical flights

of their Shamans.

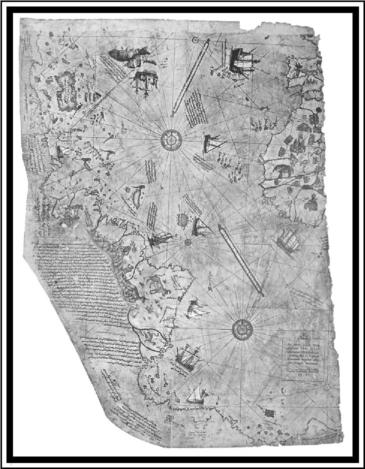

The Piri Reis

map, one of the oldest known surviving

maps showing the

Americas, first came

to light in 1929,

when historians

working in the

Topkapi Palace in

Istanbul discovered

it in a pile of rubble.

It is currently located in the Library

of the Topkapi Palace, though it is not

usually on display to

the public. The map

dates to the year

1513 and was drawn

on gazelle skin by an

admiral in the Ottoman Turkish fleet

named Piri Reis. It includes a web of

criss-crossing lines, known as rhumb

lines, common on late medieval

mariner's charts, and thought to have

been used in plotting out a course.

Close examination of the document

has shown that it was originally a map

of the whole world, but was torn into

pieces at some time in its history.

The Piri Reis Map.

The map itself is known as a

portolan chart, a type common in the

14th to 16th centuries. Such charts

were drawn up to guide navigators

from port to port,

but were not reliable

for sailing across an

ocean, as they did

not consider the

Earth's curvature.

Such an early map

showing America is

obviously of considerable historical interest, but some

would argue that its

importance lies not

merely in its depiction of the Americas. In his book

Maps of the Ancient

Sea Kings first published in 1966,

Charles Hapgood, a

historian and geographer at the University of New Hampshire, put forward the theory that the landmass

joined to the southern part of South

America at the bottom of the map can

only be a depiction of Antarctica, hundreds of years before it was discovered.

The apparently detailed rendering of

the Antarctic coastline on the chart,

including what Hapgood believed was

an accurate depiction of Queen Maud

Land, shows it without glaciers, which

would suggest the continent was

mapped in remote prehistory, before it became completely covered in ice. But

how was Stone Age man able to survey

and chart the region of Antarctica at

such an early period in human history?

Hapgood suggested the existence of

now forgotten prehistoric seafaring

civilizations, whose achievements included journeying from pole to pole

and mapping the entire surface of the

Earth at some time in the remote past.

Hapgood theorized that these civilizations left a legacy of maps, which were

hand copied over thousands of years,

perhaps by expert seafaring cultures

such as the Minoans and the Phoenicians. For Hapgood, the Piri Reis

map was, in effect, a compilation of

these ancient maps.

Later, the controversial author

Erich von Daniken considered the depiction of a pre-ice-covered Antarctica

on the Piri Reis map as evidence to

support his ancient astronaut theory,

speculating that an extraterrestrial

civilization had drawn the original

map. In his 1995 book Fingerprints of

the Gods, Graham Hancock also postulated that a previously unidentified,

highly advanced ancient civilization

existed in remote prehistory and

passed on its sophisticated knowledge

of astronomy, architecture, navigation,

and mathematics to various ancient

cultures including the Olmecs, Aztecs,

Maya, and Egyptians. He also speculated that the Piri Reis map-makers

may have used source maps compiled

by this ancient super-culture. Both

Hapgood and Hancock maintain that

the Antarctica represented on the Piri

Reis map is highly detailed, showing

mountains, rivers, and lakes, and that

it may have been based on ancient satellite surveys from the sky above Egypt.

Many scientists and archaeologists

are sceptical of Hapgood's theory in the

first place because there is no record

of such an ancient civilization that had

the resources, the technology, or most

especially the need to undertake a survey of Antarctica. What possible reason could they have had? Allowing for

the existence of this advanced prehistoric culture, does the Piri Reis map

convincingly show an Antarctica free

of ice? Most proponents of the ancient

mariner theory emphasize the accuracy of the map, especially the part

showing Antarctica, as evidence of lost

geographical knowledge. But how accurate is the Piri Reis map? The absence of the Drake Passage between

South America and Antarctica means

that if the map does show Antarctica,

then it depicts it joined to the South

American continent, with roughly 932

miles of coast from Brazil to Tierra del

Fuego left off. This would be a glaring

omission for such a supposedly accurate map.

Examining the rest of the chart,

Europe and Africa are shown in a reasonable amount of detail for the time,

though peninsulas and inlets are exaggerated, probably due to the necessity at the time of navigating by

landmarks. South America is represented as far too narrow although Brazil is fairly accurately shown. North

America, on the other hand, is poorly

drawn and enormously inaccurate, as

if based entirely on hearsay rather

than geographical knowledge, something else that would suggest there

was no ancient global survey on which

to base the map. In fact, there are earlier maps from around A.D. 1500, such

as those of Juan de La Cosa and Alberto

Cantino, which are more accurate than the Piri Reis map in terms of the positions of islands such as Cuba, Jamaica,

and Puerto Rico. One detail, which is

alleged to support the extreme antiquity of the map, is that it shows

Greenland before it was covered by ice.

However, as can be seen from a quick

perusal of the map, the top eastern

edge clearly shows the western part

of France, which is at about 50 degrees

north latitude. Consequently, if

France is represented as the most

northern country on the map, surely

Greenland cannot be depicted, and as

the map exhibits no islands which are

remotely similar to Greenland, it is

difficult to know what evidence there

is for this suggestion.

To support his theory that the Piri

Reis map depicted Antarctica under

the ice, Charles Hapgood used sounding data from Antarctic expeditions in

the 1940s and 1950s. But Hapgood's hypothesis, once thought by some as

scientifically plausible, is now in serious doubt. The insurmountable difficulty with a pre-ice-covered Antarctica

being shown on the Piri Reis map is

that when Antarctica was last free of

ice, its coastal outline would have

looked completely different than its

current shape. This is because over

time, the continental crust has been

forced down hundreds of meters, under millions of tons of ice, thus changing the shape of the underlying

shoreline completely. A comparison

between the Antarctica shown on the

Piri Reis map with a relatively recent

sub-glacial bedrock topography map of

the continent shows no similarities at

all between their coastlines. Furthermore, rather than Antarctica being

free of ice by 4000 B.c., as claimed by

Hapgood, modern geological evidence

now points to the most recent date for

an ice-free Antarctica as being more

than 14 million years ago.

But perhaps the most convincing

evidence against a prehistoric origin

for the chart can be found in the notes

written on it by Piri Reis himself. In

the early 16th century, when the Piri

Reis map was drawn, the Portuguese

had sailed across the Atlantic and

were claiming substantial parts of

South America as their own. In relation to the supposed Antarctica land

mass, the captions on the map mention

that its coast was discovered by Portuguese explorers, whose ships had

been blown off course. A particular

note on the map refers to a Portuguese

ship that landed on this coast and was

immediately attacked by unclothed natives; a further caption refers to very

hot weather. These descriptions could

clearly apply to South America, but hot

weather and naked inhabitants in Antarctica are clearly nothing more than

fantasy.

The sources for Piri Reis's map

have not all been identified by any

means, but would likely have included

the works of Greek astronomer and

geographer Ptolemy (second century

A.D.), various Portuguese maps, and

Christopher Columbus. In fact, Reis

himself notes on the chart that he copied from Columbus's maps. Many features on the Piri Reis map, including

place names and representations in

the West Indies, show that he was using at least one of Columbus's maps to

draw his own chart. Another indication that Reis was using medieval European maps is the depiction, near the

top of the chart, of a ship next to a fish,

which carries two people on its back. The note attached to this illustration

quotes a medieval story from the life

of the Irish saint, Brendan. This has

obviously been reproduced by Piri Reis

from one of his source maps, proving

that one of them, at least, was of medieval European origin.

Greg McIntosh in his The Piri Reis

Map of 1513, published in 2000, argues

that looking at contemporary maps of

the period shows that nothing in the

Piri Reis map was unknown in 1513.

He also suggests that what some have

called Antarctica on the Piri Reis map

is, in reality, the hypothetical Great

Southern Continent, which cartographers had been depicting on maps

since Ptolemy's time. The commonly

held belief was that a continent must

exist in the southern hemisphere to

balance the landmasses in the northern hemisphere. McIntosh also demonstrates that all the coasts on the Piri

Reis map south of 25 degrees are either inaccurate or wrongly placed, and

that the Antarctica depicted on Reis's

chart extends north of 40 degrees

south latitude, while the actual continent of Antarctica does not extend further than 70. In fact, rather than being

a depiction of Antarctica, a close examination of the Piri Reis map reveals

that the southern continent bears an

extremely close resemblance to the

southern half of South America, adjusted width-ways to fit onto the shape

of the parchment.

One conspicuously anomalous feature of South America on the Piri Reis

map is its apparent depiction of the

Andes mountain chain, with the rivers

Amazon, Orinoco, and Rio Plata

emerging from its base and flowing

eastwards to the coast. As the Andes

were unknown to Europeans at this

time, how did they come to be shown

on Piri Reis's map? But Reis's map is

not alone in showing a mountain range

in the interior of South America; the

Nicolo Canerio map, drawn between

1502 and 1504 and now housed in the

Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, depicts the east coast of South America

with a tree-topped chain of mountains.

From this evidence, it seems likely

that the Canerio map was another of

Piri Reis's original sources. It is also

hard to conceive that if the Piri Reis

map were based on the work of an advanced ancient seafaring culture, it

would include the Andes but omit the

Pacific Ocean. A more plausible explanation is that the mountains depicted

in the center of South America on the

Piri Reis map are east coast mountains, drawn in the wrong place and

at the wrong scale.