Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (18 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

© Government of Ireland

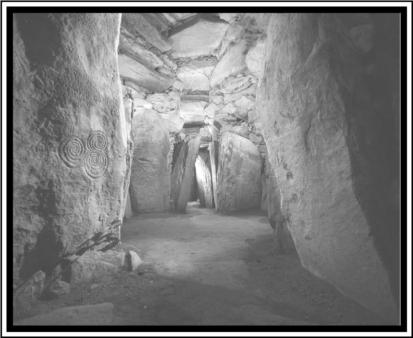

Interior of the monument, showing

megalithic art.

It has been estimated that the

Newgrange Passage Tomb contains

around 200,000 tons of material and

would have taken 300 workers a minimum of 20 to 30 years to construct.

Rounded stones from the River Boyne

were used in the construction, but the

white quartz pebbles used as facing

stones come from the Wicklow Mountains, 50 miles away, and were probably brought by boat down the Boyne. The large slabs of rock which make up

the walls and ceiling of the passageway were probably transported on

wooden rollers from a quarry 8.7 miles

away. This huge investment in time

and labor indicates a socially advanced

and well-organized people, as well as

a society of superb craftsmen.

The Passage Graves of Newgrange,

Knowth, and Dowth are justly famous

for their wealth of megalithic (c. 4500

B.c.-1500 B.C.) rock art. In fact, Knowth

alone contains a quarter of all the

known megalithic art in Europe. At

Newgrange, several of the stones inside the monument are decorated with

spiral patterns and cup and ring marks,

as are some of the kerbstones. Many of

these stones are carved on their hidden sides so as not to be visible to anyone in the tomb. But the most

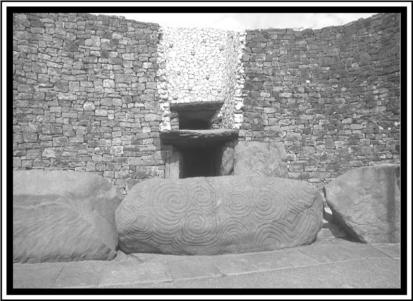

spectacular piece of megalithic art is

on the superb slab lying outside the

entrance to the tomb. This recumbent

stone is profusely decorated with lozenge motifs and one of the few known

examples of a triple spiral, the other

two examples being inside the monument. Such motifs are found on stones

in other passage tombs on the Isle of

Man and the island of Anglesey in North

Wales. Although these motifs were also

used in later Celtic art, it is not known

what they represent, though perhaps

they recorded astronomical and cosmological observations.

Surrounding the Newgrange

mound is a ring of 12 upright stones

up to 8 feet in height. Originally, there

were perhaps around 35 of these

standing stones, but they have been

removed or destroyed over time. Representing the final building stage at

the site, the circle was erected around

2000 B.C., long after the great passage

tomb had gone out of use, although its

presence shows that the area itself still

retained some importance for the local population, perhaps connected with

astronomy or ancestor worship.

Newgrange is perhaps most famous

for a spectacular phenomena that occurs at the site every year for a few

days around the 21st or 22nd of December. The entrance to the Newgrange

passage tomb consists of a doorway

composed of two standing stones and

a horizontal lintel. Above the doorway

is an aperture known as the roof box

or light box. Every year, shortly after

9 a.m. (on the morning of the winter

solstice, the shortest day of the year)

the sun begins its ascent across the

Boyne Valley over a hill known locally

as Red Mountain, the name probably

taken from the color of the sunrise on

this day. The newly risen sun then

sends a shaft of sunlight directly

through the Newgrange light box,

which penetrates down the passageway as a narrow beam of light illuminating the central chamber at the back

of the tomb. After just 17 minutes the

beam of light narrows and the chamber is once more left in darkness.

This spectacular event was not rediscovered until 1967 by Professor

Michael J. O'Kelly, though it had been

known about in local folklore before

that time. Newgrange is one of only

three known sites with such light

boxes, the other two being Cairn G, at

Carrowkeel Megalithic Cemetery,

County Sligo, Ireland, and the passage

tomb at Bryn Celli Ddu on Anglesey,

North Wales. There may possibly be a

fourth, at a chambered tomb at Crantit

on the island of Orkney, Scotland, discovered in 1998, but this is still disputed. Newgrange, however, is by far the best constructed and the most complex of these sites, and reveals in spectacular fashion the highly developed

knowledge of surveying and astronomy possessed by the Neolithic

inhabitants of the area. It also illustrates that for the people who aligned

their monument with the winter

solstice, the sun must have formed

an important part of their religious

beliefs.

© Government of Ireland

Entrance to Newgrange with huge

entrance slab displaying megalithic art.

One major aspect of the Newgrange

monument-which is often disputedis its primary function. Excavations

inside the chambers revealed relatively few archaeological finds, probably because the majority had been

removed in the centuries that the site

remained open (from 1699 until it was

examined by O'Kelly in 1962). Finds

included two inhumation burials and

at least three cremated bodies, all of

which were found close to the huge

stone basins, which seem to have been

used for holding the bones of the dead.

Taking into account the removal

of much of the material and the fact

that all of the human bones recovered

were small fragments, thus making it

difficult to clearly identify individual

burials, there must have been a lot

more than five people originally buried in the chambers. Archaeological

finds inside the monument have not

been spectacular; though a few gold

objects have been found, including two

gold torcs (a piece of jewelry worn

about the neck similar to a collar), a

gold chain, and two rings. Other finds

include a large phallus-like stone, a

few pendants and beads, a bone chisel,

and several bone pins. The lack of pottery finds at Newgrange is typical for

passage grave cemeteries, which seem

to have been places reserved for certain types of activity and an extremely

limited number of people. However, not

everyone agrees that Newgrange ever

functioned as a tomb at all. In his 2004

book, Newgrange-Temple to Life,

South African-born author Chris

O'Callaghan argues against Newgrange

being a Passage Grave. He maintains

that there is no real evidence of intentional human burial at Newgrange,

and believes that the bone fragments

found during excavations were probably brought in there by animals long

after Newgrange became disused.

O'Callaghan's theory is that the

monument was built to celebrate the

union of the Sun God with Mother

Earth, a symbol of the life force itself.

The light box or sun window would

have allowed the Sun God to penetrate

the passage of the mound (signifying

Mother Earth) and reach deep into the

chamber (symbolizing the womb). This

theory is borne out in part by the winter solstice alignment of the site, and

perhaps by the phallic shaped pillar

and chalk balls found in the chamber,

which possibly represented male sexual organs. However, Newgrange

does not need to be confined to one

function. And, as pointed out above,

the small amount of human bone discovered at the site does not seem to

represent the total of Neolithic burials within the chambers, as significant

amounts were probably taken out of

the monument, perhaps by scavenging

animals or people looking for relics.

Newgrange has many connections with

Irish myth, and was known as a sidhe

or fairy mound even into the 20th century. A number of illustrious characters from Irish mythology are

mentioned in association with it, including the Tuatha De Danann, the ancient mythical rulers of Ireland;

Aengus Og, its traditional owner; and

the hero Cuchulainn. Various mythical interpretations of Newgrange have

been put forward. These include that

it functioned as a house of the dead,

the passage and chambers being kept

dry for the comfort of the indwelling

spirits, and the roof box being opened

and closed to let the spirits in and out

of the tomb. It was also thought to be

the dwelling place of the great god

Dagda, and at specific times during the

year valuable offerings would be made

to such gods. There is actually archaeological evidence for offerings at

Newgrange long after it ceased to function as a tomb and observatory. Various Roman items, including gold coins,

pendants, and brooches-some in mint

condition-have been found at the

monument. Considering the Romans

never invaded Ireland, many of these

offerings must have been made by Romans or Romano-British visitors from

Britain, perhaps they were ancient pilgrims venerating an already 3,000-

year-old religious monument.

© Government of Ireland

The monument, as seen from a distance.

In 1993, due to their vast cultural

and historical importance, Newgrange

and the nearby passage tombs of

Knowth and Dowth were designated a

World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Newgrange now attracts in excess of

200,000 visitors per year, all of which

come on guided tours from the Bru na

Boinne Visitor Center, as there is no

longer direct access to the site. Anyone

wanting to visit around the 21st of December to witness the magnificent midwinter solstice may, however, be in for

a long wait. In 2005 there were around

27,000 applications to enter the tomb

at this time. Consequently, admission

to the Newgrange tomb chamber for

the winter solstice sunrise is only by

lottery. It is necessary to fill out an

application form, available at the reception desk in the Bru na Boinne

Visitor Center, and in early October,

50 names are drawn, 10 for each

morning the tomb is illuminated. Two

places in the chamber are then given

to each of the lucky people whose

names are drawn. One can only wonder how the Neolithic peoples of the

area chose their watchers of the midwinter solstice at this magnificent

site.

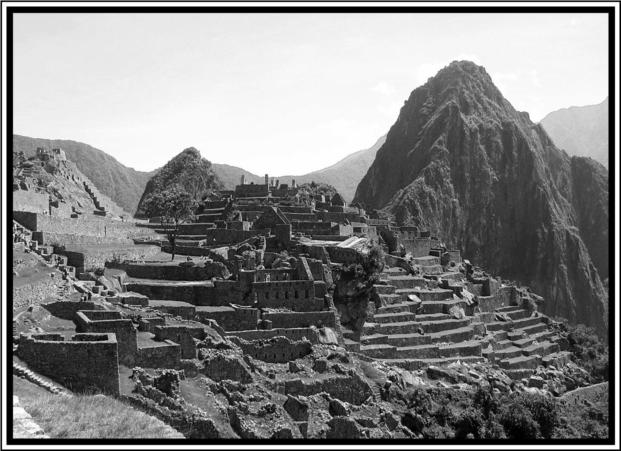

©John Griffiths.

Overall view of Machu Picchu in its stunning setting.