Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (13 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

The priest showed Churchward a

number of ancient tablets written by

the Naacal Order in a forgotten ancient language, supposed to be the

original language of mankind, which

he taught the officer to read.

Churchward later asserted that certain stone artifacts recovered in

Mexico contained parts of the Sacred

Inspired Writings of Mu, perhaps taking ideas from Augustus Le Plongeon

and his use of the Troana Codex to

provide evidence for the existence of

Mu. Unfortunately, Churchward never

produced any evidence to back up his

exotic claims: He never published

translations of the enigmatic Naacal

tablets, and his books-though they

still have many followers today-are

better read as entertainment than factual studies of Lemuria/Mu.

Zoologists and geologists now explain the distribution of lemurs and

other plants and animals in the area

of the Pacific and Indian Oceans to be

the result of plate tectonics and continental drift. The theory of plate tectonics (and it is still a theory) affirms

that moving plates of the Earth's crust

supported on less rigid mantle rocks

causes continental drift, volcanic and

seismic activity, and the formation of

mountain chains. The concept of continental drift was first proposed by

German scientist Alfred Wegener in

1912, but the theory did not gain general acceptance in the scientific community for another 50 years. With

recent understanding of plate tectonics, geologists now regard the theory

of a sunken continent beneath the

Pacific as an impossibility.

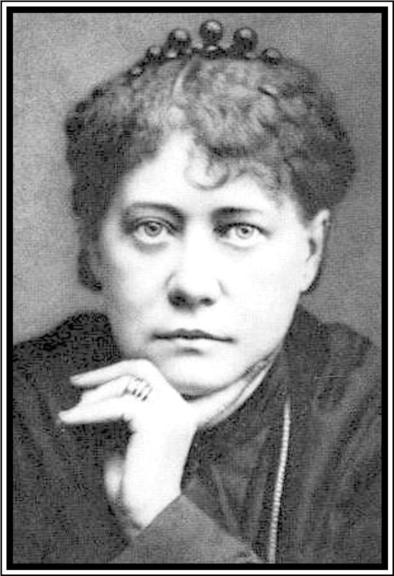

The idea of Lemuria as something

other than a physical place, perhaps

more akin to a lost spiritual homeland,

seems to derive from the writings of

colorful Russian occultist Helena

Petrovska Blavatsky (1831-1891).

Blavatsky was the co-founder (together

with lawyer Henry Steel Olcott) of the

Theosophical Society in New York, in

1875. The society was an esoteric order designed to study the mystical

teachings of both Christianity and

Eastern religions. In her massive tome,

The Secret Doctrine (1888), Blavatsky describes a history originating millions

of years ago with the Lords of Flame

and goes on to discuss five Root Races

which have existed on earth, each one

dying out in an earth-shattering cataclysm. The third of these Root Races

she called the Lemurian, who lived a

million years ago, and who were bizarre telepathic giants, keeping dinosaurs as pets. The Lemurians

eventually drowned when their continent was submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean. The progeny of the

Lemurians was the fourth Root Race,

the human Atlanteans, who were

brought down by their use of black

magic, when the continent of Atlantis

sank beneath the waves 850,000 years

ago. Present humanity represents the

fifth Root Race.

Madame H.P. Blavatsky, in New York,

1877.

Blavatsky maintained that she

learned all of this from The Book of

Dzyan, supposedly written in Atlantis

and shown to her by the Indian adepts

known as Mahatmas. Blavatsky never

claimed to have discovered Lemuria;

in fact she refers to Philip Schlater

coining the name Lemuria, in her writings. It has to be said that The Secret

Doctrine is an extremely difficult book,

a complex mixture of Eastern and

Western cosmologies, mystical ramblings, and esoteric wisdom, much of it

not meant to be taken literally.

Blavatsky's is the first occult interpretation of Lemuria, but on one level it

should not be equated with the physical continent proposed by Churchward. What Blavatsky and other

occultists have since suggested concerning Lemuria could be partly interpreted as an ideal spiritual condition

of the soul, a kind of lost spiritual

land. Nevertheless, there are some

psychics and prophets who even today

regard the existence of ancient

Lemuria or Mu as a physical reality.

Indeed, there are a few who, when hypnotically regressed, have recalled

former lives as citizens on the doomed

continent.

This is not, however, quite the end

of the story. In the last 20 years, submerged civilizations have once again

been in the news, due to a number of

intriguing underwater discoveries. In

1985 off the southern coast of

Yonaguni Island, the western-most island of Japan, a Japanese dive tour

operator discovered a previously unknown stepped pyramidal edifice.

Shortly afterwards, Professor Masaki

Kimura (a marine geologist at Ryukyu

University in Okinawa) confirmed the

existence of the 600 foot wide, 88 foot high structure. This rectangular stone

ziggurat, part of a complex of underwater stone structures in the area

which resemble ramps, steps, and terraces, is thought to date from somewhere between 3,000 to 8,000 years

ago. Some have suggested that these

ruins are the remains of a submerged

civilization-and that the structures

represent perhaps the oldest architecture in the world. Connections with

Lemuria and Atlantis have also been

mentioned. However, some geologists

with knowledge of the area insist that

the underwater buildings are natural,

and similar to other known geological

formations in the region. The debate

is still continuing on these controversial structures.

In 2001, the remains of a huge lost

city were located 118 feet underwater

in the Gulf of Cambay, off the western

coast of India. A year later, further

acoustic imaging surveys were undertaken, and evidence was recorded for

human settlement at the site, including the foundations of huge structures,

pottery, sections of walls, beads,

pieces of sculpture, and human bone.

One of the wooden finds from the city

has been given a radiocarbon date of

7500 B.C., which would make the site

4,000 years earlier than the oldest

known civilization in India. Research

is ongoing at this fascinating site,

which-if the dates are proved correctmay one day radically alter our understanding of the world's first civilizations.

Whether these underwater finds in the

Pacific and Indian Oceans prove to be

the remains of forgotten civilizations

or not, one thing is certain: Man will

always be searching for a lost homeland or a more spiritually satisfying

ancient past. In this sense, Lemuria or

Mu will always be more than just a

physical place.

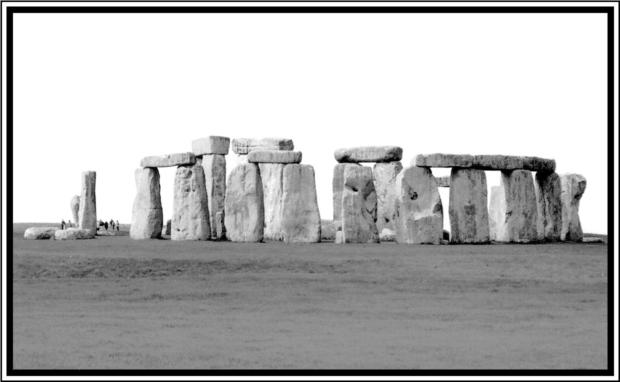

Photograph by the author.

The monumental ruins at Stonehenge brooding mysteriously on Salisbury Plain.

Looming like a group of huddled

stone giants on Salisbury Plain,

Wiltshire, in southern England,

Stonehenge is perhaps the most recognizable ancient monument in the world.

The name Stonehenge originates from

Anglo-Saxon and roughly translates

as hanging stones. But the history of

the great monument dates back thousands of years before the Saxons came

to Britain, sometime in the fifth century A.D. Its origins go back beyond the

mysterious Celtic Druids of the last

few centuries B.C., before iron was

known in Europe, and before the Great

Pyramid was erected in the sands of

Egypt. Who built this enigmatic stone

monument and what role did it play

in the prehistoric landscape of

England and Europe all those thousands of years ago?

What visitors see today when they

visit Stonehenge is a circular setting

of large standing stones surrounded by

earthworks, the remnants of the last

in a series of monuments erected on

the site between c. 3100 B.C. and 1600

B.C. During this period, Stonehenge

was built in three broad construction

phases, although there is evidence for

human activity on the site both before

and after these dates. In fact, one of

the most important and fascinating

discoveries ever made in the area of Stonehenge was that of four large

Mesolithic pits or post holes dating to

between 8500 and 7650 B.C., found beneath the modern carpark at the site.

These huge post holes had a diameter

of around 2.4 feet, and had once held

pine posts. Three of the holes were

aligned east to west, suggesting a

ritual function-it has been suggested

that they may have held totem poles,

and indeed it is difficult to see what

other purpose they could have served.

The area around Stonehenge is full of

prehistoric monuments, a number of

which were constructed in the early

Neolithic period (c. 4000 B.c.-3000 B.C.)

and thus predate the Stonehenge

monument. Examples include the long

barrow (communal burial chamber) at

Winterbourne Stoke, 1.4 miles away;

the causewayed enclosure (a type of

large prehistoric earthwork) known as

Robin Hood's Ball, 1.2 miles northwest

of Stonehenge; and the Lesser Cursus

(a long, narrow, rectangular earthwork

enclosure) 1,968 feet to the north.

Thus, when the builders of the first

stage of construction at Stonehenge

began work, they were already operating in a sacred landscape, one that

had seen ritual use for more than 5,000

years.

The first of Stonehenge's three construction phases was begun around

3100 B.C. and consisted of a circle of timber posts surrounded by a ditch and

bank. This henge, (henge used in the

archaeological sense to mean a circular or oval-shaped flat area enclosed

by a boundary earthwork) measured

approximately 360 feet in diameter,

and possessed a large entrance to the

northeast and another smaller one

to the south. This monument was dug

by hand using deer antlers and the

shoulder blades of oxen or cattle. Modern excavations of the ditch have

recovered antlers used in the construction that were deliberately left

behind by the builders of this monument. One odd fact about this phase is

that there were other animal bones,

mainly from cattle, placed in the bottom of the ditch, which proved to be

200 years older than the antler tools

used to dig the structure. It seems that

the people who buried the items kept

them for some time before burial; perhaps the bones were sacred objects

removed from a previous ritual location and brought to Stonehenge. There

is little remaining evidence for Phase

II at Stonehenge, though judging by

finds of cremated bones from at least

200 bodies, the site must have functioned as a cremation cemetary.

Phase III at the site, beginning

around 2600 B.C., involved the rebuilding of the simple earth and timber

henge in stone. Two concentric circles

of 80 bluestone pillars were erected at

the center of the monument. These

stones, weighing about 4 tons each,

were carved and transported from the

Preseli Hills, in Pembrokeshire,

southwest Wales, and brought by a

route at least 186 miles long. Apart

from the bluestones, a 16 foot long

blue-gray sandstone, now known as the

Altar Stone, was brought to

Stonehenge from near Milford Haven

on the coast to the south of the Preseli

Hills. How the bluestones arrived on

Salisbury Plain is a subject of much

controversy, though most archaeologists nowadays believe that they were

brought there by man. The most obvious way for the builders of Stonehenge

to transport the stones would have

been to drag them down to the sea at Milford Haven by roller and sledge,

and then float them to Stonehenge on

rafts by sea and river-an incredible

achievement of organization and dedication. An experiment to duplicate

this feat was undertaken in 2001, when

volunteers managed to pull a 3-ton

stone down to the sea from the Preseli

Hills in a wooden sledge on rollers, but

when the stone was placed on the raft

it slipped into the sea and sank. Intriguingly, an old legend held that

Stonehenge originated with Merlin the

wizard, who had a huge structure

known as the Giant's Dance magically

transported from Ireland. Could the

journey of the bluestones form Wales

be a disorted memory of Stonehenge

originating in the west?