Here Comes the Night (39 page)

Ahmet flew to Los Angeles and signed the act, now called Sonny & Cher, unheard and unseen, for a $5,000 advance. The first record they made for Atlantic, “I Got You Babe,” was not only a number one hit record three weeks in August in the United States, but also a huge smash across the world. Atlantic had never seen anything like it. The record was the company’s saving grace, right as the ABC sale collapsed.

Ertegun next signed a rock band called the Rascals out of Long Island. The band, dressed in knee-high knickerbockers and Peter Pan collars, had been the summer’s hot attraction in ritzy Southampton, where the Rascals pulled overflow crowds dotted with local celebrities such as Bette Davis to a funky wharfside discotheque called The Barge. Ahmet caught the band during the summer, but a number of labels showed interest. Sid Bernstein, busy producing the Beatles concert at Shea Stadium in August, managed the act (Bernstein, in fact, flashed a message, “The Rascals Are Coming,” on the stadium scoreboard during the concert).

Phil Spector flew out to see the band play and made an offer, but the group signed with Atlantic largely because Ertegun would allow the Rascals to produce their own records (alongside Atlantic “supervisors” Tom Dowd and Arif Mardin, Nesuhi’s new assistant, a brilliant Berklee College of Music graduate with the added advantage of being Turkish). The Rascals also liked the idea that they would be the only white rock group on the label. After a well-established outfit called the Harmonica Rascals screamed trademark infringement, the Atlantic legal department recommended a modifier and the group became the Young Rascals.

“I Ain’t Gonna Eat My Heart Out Anymore,” the group’s first single, was recorded in September. Berns found the song by songwriters Pam Sawyer and Lori Burton, gave it to the band, and published it with Web IV. He was, above all, an Atlantic team player.

*

Six years after its original release, British record producer John Abbey gave Berns’s production a slight revision and the record went Top Five in the U.K. in 1971.

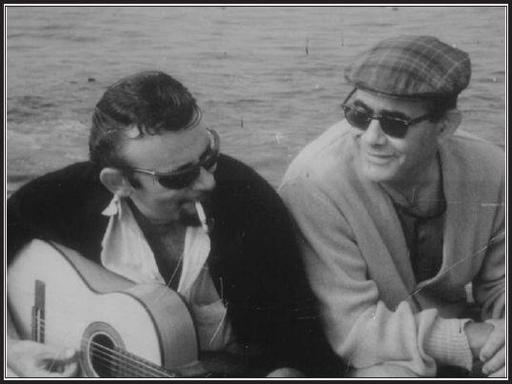

Bert Berns, Jerry Wexler

I’ll Take You Where the Music’s Playing

[1965]

B

ANG RECORDS WAS

exploding. With the label’s first single, “I Want Candy,” narrowly grazing the Top Ten, and five singles later, “Hang On Sloopy” grabbing the gold ring, the company was out of the gate like a shot. There was a power struggle from day one. Wexler wanted Julie Rifkind to report daily to Atlantic, even though he worked out of Bang at 1650 Broadway. Berns told him not to bother. Rifkind mapped out the distributors and handled the promotion and sales and Berns left him alone.

The quick success of Bang and Web IV caught the Atlantic partners by surprise. They never planned on the record label being successful—they had their own label, what did they want with another? What they did want was the half interest in Berns’s publishing that they now held. Ertegun and Wexler forced out Rifkind and hired Bill Darnell, an old big band vocalist turned record plugger, to work out of the Bang offices. Wexler also put Atlantic’s longtime independent payola consultant, Juggy Gayles, on the Bang account. Gayles had been around long enough to have plugged “God Bless America” for Irving Berlin.

Wexler called Berns on the phone three times or more daily. He carefully plotted with Berns the destiny of Bang Records, no detail too small for his attention. Berns may have thought he was running the label, but Wexler would go to any lengths to get what he wanted.

When “Hang On Sloopy” shot up the charts without benefit of a signed contract with Feldman, Gottehrer, and Goldstein, Wexler took over negotiations.

He staged a dinner for the fellows at his Great Neck place, a luxurious affair, servants waiting on everybody, bottles of fine wines uncorked, Cuban cigars smoked. Ahmet Ertegun was there, but not Berns. These outer borough kids had never seen anything like it. One bottle of the wine probably cost more than the clothes they were wearing, and Wexler, not much of a drinking man himself, made sure their glasses were always full. They signed the deal.

Berns met Andrew Loog Oldham and Tony Calder at the Bang office after George Goldner sent them over. These two British knuckleheads decided to start a record label while wheeling Oldham’s Chevy Impala through London traffic down Park Lane on their way to a taping of the TV show

Ready Steady Go!

They pulled over at Marble Arch for Calder to make a call from a phone box to get price quotes on pressing records. The next weekend, they flew to New York to make business contacts.

Oldham, who discovered and managed the Rolling Stones, had long made a habit of flying to New York, if only to see the movies and buy the records. A former teenage assistant to fashion designer Mary Quant, Oldham idolized American record men like Phil Spector and George Goldner. These weren’t people who simply had jobs in the record business and otherwise led dreary, vanilla lives. These were record men. Their work was their lives. They were a breed apart and operated by their own rules. They set the styles and pulled the strings. They had no British counterparts. Berns was one of these centurions of pop.

He played Oldham and Calder an acetate of the unreleased “Hang On Sloopy” by the McCoys. Oldham and Calder, who were about to start Britain’s first independent record label, asked if they could acquire U.K. rights. Berns wanted a $500 advance. They had to pool their resources to give him the money, but they went home with the first single for their new company, Immediate Records. “Hang On

Sloopy” launched the label in high style; number five on the charts that fall in swinging England.

Berns went back into the studio for the first time in more than a year with Solomon Burke, using Felix Cavaliere of the Rascals on organ, and redid his magnificent “Baby Come On Home” with Burke. He cut a Motownesque girl group for Bang called the Witches singing the group’s “She’s Got You Now” and the Berns-Farrell song he did with Them in May, “My Little Baby,” the first record he made for the new label, using the credit A Web IV Production.

He took the Losers, the house band from the Upper East Side niterie Ondine’s, into the studio and did two songs written by the band’s drummer for an Atco single. With the Lost Souls, another trendy Manhattan rock group from the East Fifty-Fourth Street discotheque Arthur, run by Richard Burton’s ex-wife Sybil, Berns used three of his songs on a four-song session for Bang, including “I Gave My Love a Cherry” that he tried with Them.

Berns’s “The Girl I Love” by the Lost Souls teetered on the edge of becoming a hit. (“ . . . mighty impressive Bang bow,”

Cash Box;

“Watch this one break out,”

Billboard

). Over a jangly guitar drive, the vocalist moves from despair over losing “The Girl I Love” to entreaties for someone else to

come and get me before I fall in my tears and drown

. The second section of the song, the guitar now slashing, has the singer pleading with some new girl to

help me forget how she made me a man

. Over the course of a three-minute song, Berns juxtaposes these opposing emotions to keep the singer’s turmoil in the foreground. The production catches the new rock sound of the moment, even though, as with his Them records, Berns used session musicians to substitute for some of the band’s actual members.

At night, sometimes he and Ilene would climb aboard his Harley and ride down to the Village to grab a piece of pizza and catch a foreign film at the Waverly. Sometimes he would hit the art galleries on the weekends. He worked most of the time, office at day, sessions at night.

They had a modest sex life, tempered by his heart problems, but he couldn’t fall asleep until his wife curled an arm and leg around him. He loved being a father. He thought his illness had left him sterile. He still flew through a couple of packs of cigarettes a day and there were always pill bottles lying around.

For his young bride, the routine was stultifying. He took her to Miami by train—Berns hated to fly—for the r&b disc jockey convention and she sunned herself by the pool while Berns schmoozed the deejays. He doted on the dog and she focused some of her resentments on Dino, who slept on their bed every night and could be powerfully flatulent. The giant Great Dane was untrained, clumsy, and liked to jump up and put his paws on people’s shoulders. They quarreled about the dog. At one point, Ilene, who may have been somewhat unsophisticated, but was by no means any shrinking violet, laid down an ultimatum—the dog or me. Berns angrily moved out of the penthouse.

He complained aloud in the studio to Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles, a girl group out of Philadelphia recently signed to Atlantic by Wexler. “I can always get another wife,” he growled. The girls were a little shocked, but also secretly amused.

These four young ladies first hit the charts three years earlier with “I Sold My Heart to the Junkman” with a small Philly independent. Actually the record hit the charts before they did. They almost failed the audition without singing—the label head took one look and declared lead vocalist Patti Holte too plain looking and too black, but then he heard her sing.

The label chief named her Patti LaBelle and called the group the Bluebelles. The record by the Bluebelles was already on the charts—the recording had been done by another group signed to another label—but it was Patti Labelle and her three associates, Wynona Hendrix, Sarah Dash, and Cindy Birdsong, who lip-synched the record on

American Bandstand

before returning to the studio to rerecord the song themselves.

They had taken some decent shots on other labels and toured on r&b bills all over the country before Wexler signed the group. One of the first things they did for Atlantic was put some background vocals on a new Wilson Pickett recording from Memphis, “634-5789,” and then Wexler turned them over to Berns to record.

Berns took them pop, pitching Patti LaBelle’s high-flying vocals against a crashing wall of horns and strings on the powerful first single, “All or Nothing,” from songwriters Pam Sawyer and Lori Burton, who wrote “I Ain’t Gonna Eat My Heart Out Anymore,” the song Berns gave to the Rascals. Berns tossed a song on the B-side cowritten with his wife, under the name Ilene Stuart, “You Forgot How to Love,” a lot of the lyrics written by his wife after a marital spat.

Wexler had high hopes for the record. He circulated a typewritten letter over his signature to program directors and disc jockeys: “‘Fantastic’ is a word I rarely use, but I think our first Atlantic record with Patty and the Bluebells [sic] ALL OR NOTHING is just that—fantastic. I’m sure that after you listen to it, you’ll agree that ALL OR NOTHING will be a Top 10 record.”

The record sputtered around the bottom of the charts for a few weeks and then disappeared altogether. On the next single, Berns backed the A-side, LaBelle’s star turn on “Over the Rainbow,” with “Groovy Kind of Love,” the first recording of a song by Screen Gems writers Toni Wine and Carole Bayer Sager that would become a number two hit the next year by British pop group the Mindbenders.

He did an updated version of “A Little Bit of Soap” with the Exciters on Bang that stirred some action but never charted. He also had them cover the old Russell Byrd song “You Better Come Home” and another Berns-Farrell piece, “You Know It Ain’t Right,” an echo from the “Here Comes the Night” rewrite, “There They Go.” Berns didn’t waste a lot of songs. He didn’t like to waste even

parts

of songs. He was recording almost everything he was writing and working the catalog as hard as he could.

Ilene made her peace with Dino. There had probably never been any real question. She was clearly smitten with Berns, caught up in the world in which he walked, pulled into the whirlwind that was his life. Berns was a happy man, living a life full speed at the top, a prince of the industry, a master of Broadway.

He and Jeff Barry started spending a lot of time together, taking off during the day to shoot pool around the corner on Seventh Avenue for a nickel a ball. They bought each other pool cues. Berns, always flush with cash, was an easy touch for quick loans—twenty, fifty, a hundred, what do you need? He wasn’t always so good at remembering to whom he loaned what. But when Barry owed him a quarter at the end of a pool session and had only bills in his wallet, Berns made him get change.