Here Comes the Night (31 page)

These were experimental sessions for Berns. He had no idea what to expect and gave the acts retreads of songs that already failed to ignite much interest in the States, but at least he was working the catalog. The talent wasn’t extraordinary, but there was a fresh energy in the air. Nothing much happened with any of the tracks he cut that day.

“Come On Girl” showed up on the B-side of the second Redcaps single. Rowe signed the group, whose claim to fame was having opened for the Beatles on four occasions. Rowe took Gerry Levene and the Avengers back into the studio and cut a handful of r&b songs, including “Twist and Shout.” He had better luck with his Rolling Stones,

who hit the UK charts that November with a number custom-tailored for the group by Beatles songwriters Lennon and McCartney, “I Wanna Be Your Man.”

Berns went with Mellin to spend the weekend at his Surrey country manor. They hammered out a new publishing agreement and Berns couldn’t help but be impressed by the baronial pastoral surroundings. Mellin’s wife Patricia owned a Great Dane that entranced Berns, and before the weekend was over, she took him to visit the breeder and he ordered a dog to be shipped to him in the United States.

In the December 7, 1963, issue of

Billboard

, a few weeks after Berns returned to New York, tucked away in the back of the magazine with the international news, was a photograph of Sir Joseph Lockwood presenting the four Beatles with silver record awards, with the following caption:

Members of the Beatles, hottest British group, receive their two silver LP awards from EMI chairman Sir Joseph Lockwood for sales well over the 250,000 mark on each of their albums, “Please Please Me” and “With the Beatles.” The latter award was given two weeks ahead of the release of the LP. Advance orders stood at an unprecedented 345,000. At the same ceremony, the group was given a miniature silver EP to mark sales of 400,000 for their first EP “Twist and Shout.” The boys have racked up a total sale of four million on the sum total of all singles, EP’s and LP’s

.

IT WAS A

photo of a tidal wave offshore and nobody saw it coming.

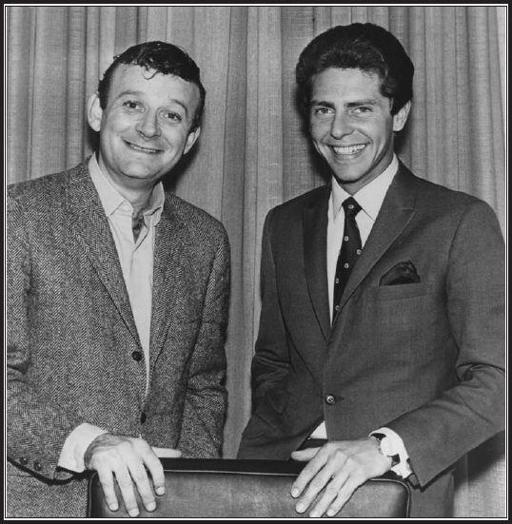

Bert Berns, Wes Farrell

W

ES FARRELL WAS

the master of the short relationship. Well dressed and well groomed, he was the first man Dion saw with manicured nails. He wore custom-tailored mohair suits and monogrammed shirts and drove a Jaguar XKE. His girlfriend was a society doll, the beautiful blonde daughter of a prosperous Long Island car dealer. Luther Dixon brought handsome, dashing Farrell to the studio when he recorded the Shirelles singing the song he and Farrell wrote for the flip side of “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “Boys,” just so the girls could see what they were singing about. Farrell formed Picturetone Music in 1963 with Phil Kahl, a questionable character who ran Morris Levy’s publishing empire for years. He and his brother Joe Kolsky had always been shadowy figures in the background at Levy’s operation at Roulette Records (and before), but Kahl left the year before and started this new company with twenty-five-year-old Farrell in an office at 1650 Broadway.

Farrell had a certain kind of front that worked well in the music business. He could sing, but he wasn’t much of a musician. He was slick, and he knew the score. He could get songs in front of the right people. When he was working as professional manager at Roosevelt Music, Farrell found himself hanging around the company offices with

nine other songwriters, trying to come up with something on a deadline for Pat Boone. He tossed out the title—“Ten Lonely Guys”—and supplied the bottle of Scotch.

Before the evening was through, they had not only knocked out a jokey country and western parody, but also gone downstairs and cut the demo at Allegro Studios in the basement, lead vocals provided by a junior Roosevelt writer named Neil Diamond. The crazy bastards liked the demo so much, they took it over to Joe Kolsky and Phil Kahl, who were running Diamond Records down the hall on another floor, and everybody was convinced for a minute that it was a hit.

Sanity did prevail, as Hal Fein, who ran Roosevelt, refused to grant the Diamond Records guys a license and instead gave the song after all to Pat Boone, who put the dumb thing on the charts. Farrell, like everyone else, had only a one-tenth writer’s share, but he got his extra taste under the table from Fein.

Dion wrote a couple of songs with Farrell. He was off the charts, looking to find his way back, and Farrell impressed Dion with his affability and high style. He found Farrell good company, a collaborator who took him places he might not otherwise have gone, but otherwise someone who contributed little, not that Dion begrudged him the songwriting credits.

Berns and Farrell produced a flurry of songs that winter, while producer Berns busily slapped them on records within days of each other—“Baby Let Me Take You Home” by Hoagy Lands, “Goodbye Baby (Baby Goodbye)” by Solomon Burke. Farrell and Berns took to the studio themselves, singing together like a pair of deranged Everly Brothers. As the Mustangs, Berns and Farrell cut a rock and roll version of “Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand” and a couple of other pieces. Berns was absorbing the lessons of the British rock scene, incorporating the changes in his own music, even if he couldn’t quite abandon all his trademark brushstrokes (the Mustangs, for instance, featured Cissy and the girls singing

giddyup

in the background).

They made a Wes Farrell single together for Capitol, a strange, calypso-flavored song about visiting a girlfriend’s apartment when she’s not home and leaving behind a note, Berns singing the payoff on the chorus in his exaggerated, Elvis-y vibrato.

I drank your coffee, I played your records

I touched your pillow and I talked to your cat

.

I was happy for a little while

I just stopped by to thank you for that

.

—

THE LETTER (BERNS-FARRELL, 1964)

They wrote “My Girl Sloopy” at Berns’s office at 1650 Broadway. As he did with “Twist and Shout,” Berns drew the chords and the feel straight from “La Bamba,” although “Guantanamera” was another obvious reference point. The Cuban love song was originally introduced in the late twenties by Joseito Fernandez, a shoemaker who started singing with

son

groups as a teenager. He first recorded the song in 1941, but it was his daily improvisations when he sang it as the theme song to a popular Cuban radio show through the forties and fifties that burned the airy melody into the country’s brains. When orchestra leader Julian Orbon adapted verses to the song from the poetry of Jose Martí, the greatly beloved Cuban revolutionary who died fighting for his country’s freedom in the nineteenth century, the song ascended into an unofficial national anthem. Folksinger Pete Seeger popularized the number throughout the English-speaking world, but nobody would find more utilitarian use for the piece’s endlessly appealing chord changes and rumbling bass line than Berns.

As soon as Farrell left, Berns pulled songwriter Artie Wayne out of the hallway to play him the freshly minted song. Berns sat down at the piano and began pounding out the r&b

guajiro

, and by the time he reached the chorus the second time, Wayne was singing along at the top of his lungs and the girls from the office peered around the doorways to listen.

The presence of a collaborator notwithstanding, “My Girl Sloopy” was pure Berns, cut from the same blueprint as “Twist and Shout,” a Romeo and Juliet story about a girl with a funny nickname cast in the authentic sound of the street. Solomon Burke turned the song down, but Berns didn’t have far to look to find the perfect vehicle for his material. The Vibrations had signed a quick deal the year before with Atlantic and released a single on the label the previous fall written by one of the members, that had gone nowhere. The group actually boasted practically the perfect pedigree for the seriocomic “My Girl Sloopy.”

The members first met at high school in Los Angeles in the fifties, when the group was called the Jayhawks. Their 1956 hit, “Stranded in the Jungle,” written by a couple of the group members, brilliantly juxtaposed parallel narratives, each with its own signature rhythm, switching back and forth between the song’s protagonist being boiled alive by cannibals in Africa and (

“meanwhile back in the States . . .

”) his girlfriend back home being romanced by some slick guy. Recorded for a tiny Los Angeles independent, the Jayhawks version got beat out on the charts by an uptown cover from the Cadets on the Modern label across town. Nevertheless the group managed to survive.

By 1961, now calling themselves the Vibrations, the five singers cut the Top Thirty pop hit “The Watusi” for the Checker label in Chicago. About the same time, they did a quick session off the books in Los Angeles for producer Fred Smith, whose regular vocal group, the Olympics (“Hully Gully”), was on tour in the East Coast. He released the track “Peanut Butter” by the Marathons, but Checker soon figured the ruse and handed the matter over to the attorneys. For a while, the group wore matching sweatshirts onstage with the letter

V

on their chests, changing to ones with the letter

M

when they did their other hit.

But the Vibrations did not depend on these comic, novelty hits for the group’s longevity; they had a polished, acrobatic stage act—flips,

splits, and leapfrogs, far more frenetic than the customary, almost military drill squad precision of most r&b acts of the day. By the time the Vibrations came to Atlantic, the group had made more than twenty records in nine years in the business. They met with Berns at his apartment, only to be greeted by a huge dog bounding up and slobbering on them as soon as they stepped off the elevator.

Dino had taken over the place since arriving from the British kennel a few months before. He joined the Berns menagerie already in progress, the two Siamese cats, Keetch and Caesar. The giant dog chewed to shreds what little furniture there was. Dog hair was everywhere, and since bachelor Berns was not the most diligent of dogwalkers, the terrace around the apartment where Berns allowed Dino to roam was filled with dog shit. He spoiled the beast shamelessly, routinely feeding him steak and burgers.

The Vibrations were not immediately impressed with the song, but Berns put them through rigorous paces. He knew what he wanted and he paid close attention to what some of the vocalists thought were minor details. After the end of the routining, the song sounded more promising. When the group faced a studio full of top sidemen and heard the badass backbeat they laid down, the Vibrations began to see the beauty of “My Girl Sloopy.”

The record turned out to be a masterpiece of production by Berns. He brings the compact, expertly orchestrated piece to two brisk crescendos—shades of “Twist and Shout”—and manages to distill unfiltered Afro-Cuban voodoo for the pop charts. The obviously fake crowd noise turns up the heat on the track. He draws from vocalist Carl Fisher a peerless, loopy performance that straddles the borders of humor, lust, and hard soul, leavened with just the right touch of jive. As he did during rehearsals, Wes Farrell watched from a couch in the corner.

Berns dove into his work at Atlantic. A week after his session with the Vibrations, he went into the studio with Ben E. King for the first time. They cut a couple of songs, including “That’s When It Hurts,” a

slight rewrite of the unreleased song Berns recorded as Russell Byrd for Atlantic a few months before. The songwriting credit was shared between Berns and Wexler, although Wexler did little more than pour the drinks and

kibitz

while Berns wrote the song one Sunday afternoon at the piano in Wexler’s Great Neck mansion, where he spent many weekends.

His first single with the Drifters, “Vaya con Dios,” the old Les Paul and Mary Ford hit he recorded in December, was heading up the charts. His Hoagy Lands single on Atlantic was making noise (“The singer really preaches on this one,” said

Billboard

, “from the opening recitation to the wailing finish . . .”).

He was preparing Esther Phillips on four songs for a February session. The onetime Johnny Otis teenage protégé, whose “Double Crossing Blues” was a number one r&b hit in 1950 when she was known as Little Esther Phillips, had recently signed with Atlantic. She was handled by Alan Freed’s old bagman, Jack Hooke, who was also her lover, and was coming off a 1962 Top Ten hit with the country and western song “Release Me” for a small Nashville label that subsequently went kaput. Her career on an upswing, she was off drugs for the time being.

In March 1964, Berns introduced Keetch Records, his own label to be distributed by Atlantic. The record label joined his new joint publishing venture with Bobby Mellin, called Keetch, Caesar & Dino Music, in bringing his animals into the act. A cartoon drawing of a Siamese cat decorated the label.