Here Comes the Night (27 page)

Greenwich was all music and theirs was a romance in song. There was music for them everywhere. They sat in a car parked at a lovers’ lane, laughing at the other couples making out, as they scribbled a half-baked song they called “Hanky Panky” that they would record as the Raindrops. Adorable Greenwich wore white lipstick and bouffant beehives. Long, lanky Barry dressed like the Marlboro Man, cowboy hats, jeans, and boots. They were a welcome addition to the Leiber and Stoller world.

Leiber and Stoller parted company with Talmadge and United Artists, but they still needed an outlet for their songs. They decided to

revive their Tiger Records label, defunct since last year’s Tippie and the Clovers bossa nova novelty. They always modeled themselves after Tin Pan Alley titans such as Gershwin, Berlin, or Porter, and they were like the old-time moguls themselves now, managing their publishing portfolios, keeping young writers on staff, cutting deals to make records. They were earning more on their end of the Barry and Greenwich hits with Spector than they were with their own songs.

They were living out the destinies that began when they composed their first songs at a piano under a photograph of George Gershwin inscribed to Stoller’s mother. They dressed like bankers and ate and drank like rajahs at Midtown watering holes like the Russian Tea Room. Since splitting with United Artists, they had developed a stockpile of recordings that they owned, now that UA wasn’t paying for them, and putting them out seemed like the best way to get their money back.

Their first record on the new label, “Big Bad World” by Cathy Saint, produced by Jeff Barry, was released the same week President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Not a good week for a record titled “Big Bad World.” (The nation’s dour mood also chilled the response that year to Phil Spector’s masterpiece Christmas album featuring all the Philles Records artists,

A Christmas Gift for You

). It was a bad start to something that wasn’t going to end well at all.

*

Vocalist Astrud Gilberto, who spoke some English and accompanied her reclusive husband to the United States for his Carnegie Hall appearance, was talked into singing the English lyrics on the recording of “The Girl from Ipanema,” convinced it was only a demo version, even though she was a housewife who had never before sung outside her home, which may help account for the stark, undecorated innocence of the vocal performance.

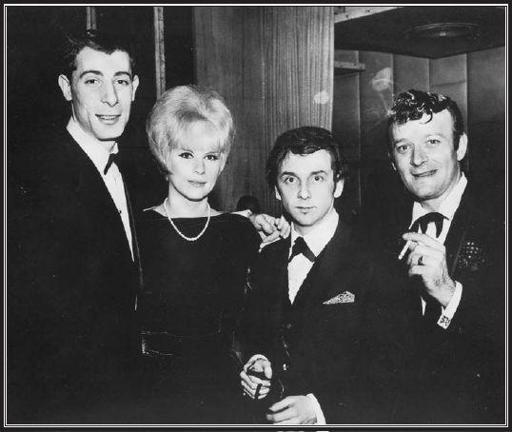

Jeff Barry, Ellie Greenwich, Phil Spector, Bert Berns, BMI Awards dinner, 1963.

T

HIS WAS THE

golden era of rhythm and blues. Berns’s records with Solomon Burke not only bailed out Atlantic Records, but also made Burke one of the music’s crown princes, alongside such regal peers as Sam Cooke and Jackie Wilson. James Brown was emerging as an inexhaustible, indomitable showman. Ray Charles had reached a mainstream audience previously thought impossible for any black entertainer, chiefly through his 1962 breakthrough album of country songs,

Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music

, that included the massive hit “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” The music had evolved into sophisticated, ingenious realms of expression, far beyond its humble beginnings only a few years earlier.

Bert Berns was also very much in the Leiber and Stoller orbit at the start of 1963. His “Tell Him” by the Exciters (number four Pop) was the biggest hit Leiber and Stoller had managed for United Artists. His production for them on Baby Jane and the Rockabyes did better than anyone expected. He brought them some music. Ahmet Ertegun said it reminded him of Gypsy music and gave the song its title, “Gypsy,” (and himself a piece of the songwriting). Leiber and Stoller finished the song and cut it in January 1963 with Ben E. King, while Berns watched. It was the first time he and Ben E. King met.

The same four writers shared credits on another number. Ertegun again supplied the title, “You Can’t Love ’Em All,” and Berns gave the piece a Cubano lilt, while Leiber finished the song with his trademark comic touch. Stoller went over to Berns’s penthouse one afternoon and the two of them batted out another pair of songs, “His Kiss” and “You’ll Never Leave Him.” Leiber and Stoller let very few associates into their charmed songwriting circle, but now Berns qualified as one of the elite. His records with Solomon Burke established his bona fides by themselves.

Burke was now the big Atlantic star, and when Wexler found a song he wanted to record, it went to Burke. Berns’s next session with Burke in March 1963 revolved around a song Wexler found on a tape that came in the mail from Detroit. Of the eight songs on the tape, only one impressed Wexler, called “If You Need Me.” He paid $1,000 for the publishing to the song but, for some reason, failed to acquire the rights to the demo. Other labels would have simply purchased the demo and released it, but Atlantic liked to build their artists and sought out suitable material from all kinds of outside sources. Arranger Garry Sherman hewed close to the arrangement on the demo and Burke sang it down to the ground.

“Can’t Nobody Love You,” also recorded at the same session, led off with a blues figure picked on an acoustic guitar, as the song slowly built to the gospel chorus entrance. Berns gave his soul–folk touch to “Hard Ain’t It Hard,” a Woody Guthrie song popularized by the Kingston Trio that Berns outfitted with big acoustic guitars and a female background chorus. He also cut the Berns-Leiber-Stoller-Ertegun piece “You Can’t Love ’Em All,” a supple, Cubanized take on the Leiber-Stoller formula for the Drifters with Afro-Cuban percussion instead of Brazilian and a booming bass straight off a mambo record. With mariachi horns punctuating the chorus, the track glides into Burke’s wheelhouse. He moves easily into Leiber’s sly braggadocio.

You can’t love them all

, the girls sing.

No, I can’t ’cause I’m only one guy

, Solomon sings.

No, you can’t love ’em all

, sing the girls.

No, you can’t love ’em all. No, I can’t

, sings Solomon,

but I’m sure gonna try

.

These were robust productions, delicately flavored, superbly crafted with authority and grace, all in service of Burke’s iridescent vocals and the song. Berns had matched Solomon Burke’s formidable character with a musical style that made him one of the leading rhythm and blues performers of the day. Burke may have been the star, but they were Berns’s records. Other record men like Ertegun and Wexler or Leiber and Stoller knew how good these records were, even if they didn’t call attention to themselves like Phil Spector’s bombastic productions from the coast. In the closely watched, highly competitive insular world of New York rhythm and blues, Berns had made his mark.

Before Wexler could release the new Solomon Burke single of “If You Need Me,” he got wind that singer Lloyd Price and his partner Harold Logan, an unpleasant and unscrupulous man even in the relative morality of the rhythm and blues world, had purchased the demo of the song, which featured a former gospel vocalist named Wilson Pickett, fresh out of the vocal group the Falcons, who put “I Found a Love” on the charts the year before. Wexler met with Logan, who wanted Atlantic to kill the Burke record and lease his Wilson Pickett record instead. Wexler offered them a piece of the Burke record, in exchange for giving him the Pickett version, which he would release later (maybe). They could not come to terms and Lloyd and Logan put out the Wilson Pickett single of “If You Need Me” on their own Double L label, which they got Liberty Records to distribute, the same week that the Solomon Burke record hit the chutes on Atlantic (the same week also as Phil Spector’s “Da Doo Ron Ron” by the Crystals).

Wexler went to work. He knew Liberty couldn’t promote a record like he could. He burned up the phones. He wheedled, cajoled, did anything he could to pump that record. He was furious at the effrontery

and a little pissed at himself for not coming up with another grand for the demo in the first place. Wexler went to war. When the smoke cleared, he had clobbered Liberty. Solomon Burke’s record went all the way to number two on the r&b charts and blew the Pickett version off the charts after only one week. A year later, Wexler walked into a hotel bar during a disc jockey convention, and Al Bennett, chief of Liberty Records, spotted him. “Don’t mess with this man,” Bennett announced to anyone who could hear.

Under their deal with United Artists, Berns went back into the studio for Leiber and Stoller with Baby Jane and the Rockabyes. In addition to a follow-up to the surprise hit, “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window,” Berns cut a pair of his songs with only the female vocalists in the group. He called this girl group configuration the Elektras and gave the record to United Artists. He had made “It Ain’t as Easy as That” before with Hoagy Lands, but “All I Want to Do Is Run,” cowritten with Baby Jane bass vocalist Carl Spencer, was pure Berns heartache and despair.

Leiber and Stoller may have split with United Artists, but Berns started bringing acts on his own to United Artists without missing a beat, beginning with the Isley Brothers, who were done with Scepter. Berns cut a surprisingly desultory session of two songs written by the Isleys, “Tango,” a patently silly dance novelty that Ronnie Isley nonetheless sang the crap out of, and “She’s Gone,” the kind of plodding, lifeless ballad Berns knew would never be commercial. But the door at UA was open to Berns and he wanted to make a move.

Jerry Ragovoy found Garnet Mimms and the Enchanters in Philadelphia. A friend took him to see Mimms and his group singing gospel in a nightclub. Ragavoy, who grew up in Philly, dropped out of school and left home when he was sixteen. He had always fooled around on the piano and, outside of a few weeks of lessons when he was a teen, was entirely self-taught. Nevertheless he wound up making a living as a children’s piano teacher. He studied classical music and learned to write orchestrations.

He landed a job, little more than a gofer, working for Peter DeAngelis and Bob Marcucci, the Philadelphia record producers behind teen idols Frankie Avalon and Fabian. Ragovoy wrote a couple of charts for Frankie Avalon sessions, found a song or two, soaked up some experience. He studiously composed a song he felt contained all the elements of a hit record and found a vocal group called the Majors to sing his song. Financing the session himself with his $1,200 savings, Ragovoy took the master around New York and was roundly rejected by every label in town, before finally selling the track (and half the publishing) to the East Coast office of Hollywood-based Imperial Records for $500. In the meantime, he quit his job in Philly, moved to New York, and started working for Sammy Kaye at the Brill Building. When “A Wonderful Dream” by the Majors came out in fall 1962 and hit the charts, three weeks later he left that job.

Ragovoy knew Berns from Philadelphia, when Berns would come down to represent Mellin material to DeAngelis and Marcucci. Berns gave him studio work in New York and showed him around town. He took an amazed Rags to a bar where a couple of dozen young Jewish women were drinking and talking loudly. He wrote a friend that New York Jews made Philadelphia Jews look like

goyim

. Although Ragovoy had dark-complexioned good looks, he marveled at Berns’s bachelor ease. He also admired Berns’s intuitive musical gifts, nose for talent, and street smarts.

Garnet Mimms was a twenty-six-year-old from Philadelphia who made his first gospel record as a member of the Norfolk Four in 1953. After a stint in the service, he started singing with vocal groups in Philly in 1958. The Gainors cut eight singles over the next three years for a number of labels. Their first, a cover of a pop song by

Oklahoma!

star Gordon McRae called “The Secret,” even made some noise around town. But Mimms had disbanded the group and returned to singing gospel by the time he met Ragovoy. He and Sam Bell from the Gainors found another couple of singers, but they didn’t call themselves Garnet Mimms and the Enchanters until Ragovoy signed them.

Ragovoy had been working on the song “Cry Baby” for a couple of years. He had the title. He had the melody. He wrote the lyrics. But he could never fit it together. He kept the song in the drawer, and every couple of months, he would pull it out and fuss with it. One afternoon at Ragovoy’s Upper West Side apartment, he sat at the piano and played what he had for Berns. In no time, Berns wrote the recitation that serves as the song’s bridge and figured out the ending. The gospel-flavored ballad was right down his alley.