Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes (9 page)

Read Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Since Cuvier didn’t know the laws of rational morphology (we now suspect that they do not exist in the form he anticipated), he proceeded by his favorite method of empirical cataloging. He amassed an enormous collection of vertebrate skeletons, and noted an invariant association of parts by repeated observation. He could then use his catalog of recent skeletons to decide whether fossils belong to extinct species. The earth, he argued, has been explored with sufficient care (for large terrestrial mammals at least) that fossil bones outside the range of modern skeletons must represent vanished species.

The four volumes of the 1812 treatise form a single long argument for the fact of extinction, the resultant utility of fossil vertebrates for ascertaining the relative ages of rocks, and the consequent antiquity of the earth. The introductory

Discours préliminaire

sets out basic principles. In the first technical monograph, on mummified remains of the Egyptian ibis, Cuvier finds no difference between modern birds and fossils from the beginning of recorded history as then construed. The present creation therefore has considerable antiquity; if extinct species inhabited still earlier worlds, then the earth must be truly ancient. The next set of monographs discusses the detailed anatomy of large mammals found in the uppermost geological strata—Irish elks, woolly rhinos, and a variety of fossil elephants (mammoths and mastodons). They are similar to modern relatives, but the sizes and shapes of their fragmentary bones lie outside modern ranges and will not correlate with the normal skeletons of living forms (no modern deer could hold up the antlers of an Irish elk). Hence, extinction has occurred and life on earth has a history. The final monographs demonstrate that still older bones belonged to creatures even more unlike modern species. Life’s history has a direction—and great antiquity if it has passed through so many cycles of creation and destruction.

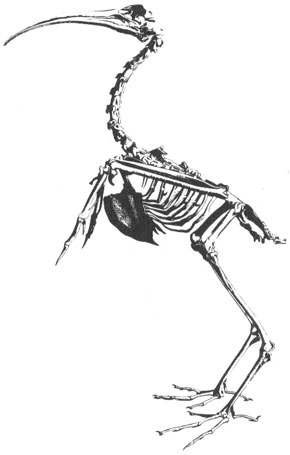

Mummified skeleton of an Egyptian ibis, from Cuvier’s

Ossemens fossiles

of 1812. Cuvier showed that this bird is identical with modern ibises and that no organic changes had occurred during the long period from ancient Egypt to today. Since so many changes had occurred in earlier periods, the earth must be ancient.

Cuvier did not give an evolutionary interpretation to the direction that he discerned, for the very principle that he used to establish extinction—the correlation of parts—precluded evolution in his mind. If an animal’s parts are so interdependent that each one implies the exact form of all others, then any change would require a total remodeling of an entire body, and what process can accomplish such a complete and harmonious change all at once? The direction of life’s history must reflect a sequence of creations (and subsequent extinctions), each more modern in character. (We would not deny Cuvier’s inference today, but only his initial premise of tight and ubiquitous correlation. Evolution is mosaic in character, proceeding at different rates in different structures. An animal’s parts are largely dissociable, thus permitting historical change to proceed.)

Thus, ironically, the incorrect premise that has sealed Cuvier’s poor reputation today—his belief in the fixity of species—was the basis for his greatest contribution to human thought and hard-nosed empirical science: a proof that extinction grants life a rich history and the earth a great antiquity. (I note the further irony that Cuvier’s creationism—good science in his time—disproved, more than 150 years ago, the linchpin of modern fundamentalist creationism: an age of but a few thousand years for the earth—see essays of section 5).

Cuvier’s reputation took a second strike from his adherence to (and partial invention of) the geological theory of catastrophism, a complex doctrine of many parts, but focusing on the claim that geological change is concentrated in rare episodes of paroxysm on a global or nearly global scale: floods, fires, the rise of mountains, the cracking and foundering of continents—in short, all the components of traditional fire and brimstone. Cuvier, of course, linked his catastrophism to his theory of successive creations and extinctions by identifying geological paroxysms as the agent of faunal debacles.

A perverse reading of history had led to the usual claim—as in the textbook assessment of Cuvier cited earlier—that catastrophism was an antiscientific feint by a theological rear guard laboring to place Noah’s flood under the aegis of science, and to justify a compression of earth’s history into the Mosaic chronology. Of course, if the earth is but a few thousand years old, then we can only account for its vast panoply of observed changes by telescoping them into a few episodes of worldwide destruction. But the converse does not hold: a claim that paroxysms sometimes engulf the earth dictates no conclusion about its age. The earth might be billions of years old, and its changes might still be concentrated in rare episodes of destruction.

Cuvier’s eclipse is awash in irony, but no element of his denigration is more curiously unfair than the charge that his catastrophism reflects a theological compromise with his scientific ideals. In the great debates of early-nineteenth-century geology, catastrophists followed the stereotypical method of objective science—empirical literalism. They believed what they saw, interpolated nothing, and read the record of the rocks directly. This record, read literally, is one of discontinuity and abrupt transition: faunas disappear; terrestrial rocks lie under marine rocks with no recorded transitional environments between; horizontal sediments overlie twisted and fractured strata of an earlier age. Uniformitarians, the traditional opponents of catastrophism, did not triumph because they read the record more objectively. Rather, uniformitarians, like Lyell and Darwin, advocated a more subtle and

less

empirical method: use reason and inference to supply the missing information that imperfect evidence cannot record. The literal record is discontinuous, but gradual change lies in the missing transitions. To cite Lyell’s thought experiment: if Vesuvius erupted again and buried a modern Italian town directly atop Pompeii, would the abrupt transition from Latin to Italian, or clay tablets to television, record a true historical jump or two thousand years of missing data? I am no partisan of gradual change, but I do support the historical method of Lyell and Darwin. Raw empirical literalism will not adequately map a complex and imperfect world. Still, it seems unjust that catastrophists, who almost followed a caricature of objectivity and fidelity to nature, should be saddled with a charge that they abandoned the real world for their Bibles.

Cuvier’s methodology may have been naïve, but one can only admire his trust in nature and his zeal for building a world by direct and patient observation, rather than by fiat or unconstrained feats of imagination. His rejection of received doctrine as a source of necessary truth is, perhaps, most apparent in the very section of the

Discours préliminaire

that might seem, superficially, to tout the Bible as infallible—his defense of Noah’s flood. He does argue for a worldwide flood some five thousand years ago, and he does cite the Bible as support. But his thirty-page discussion is a literary and ethnographic compendium of all traditions, from Chaldean to Chinese. And we soon realize that Cuvier has subtly reversed the usual apologetic tradition. He does not invoke geology and non-Christian thought as window dressing for “how do I know, the Bible tells me so.” Rather, he uses the Bible as a single source among many of equal merit as he searches for clues to unravel the earth’s history. Noah’s tale is but one local and highly imperfect rendering of the last major paroxysm.

As a rough rule of thumb, I always look to closing paragraphs as indications of a book’s essential character. General treatises in the pontifical mode proclaim a union of all knowledge, or tell us, in no uncertain terms, what

it

all means for man’s physical future and moral development. Cuvier’s conclusion is revealing in its starkly contrasting style. No drum rolls, no statements about the implications of catastrophism for human history. Cuvier simply presents a ten-page list of outstanding problems in stratigraphic geology. “It appears to me,” he writes, “that a consecutive history of such singular deposits would be infinitely more valuable than so many contradictory conjectures respecting the first origin of the world and other planets.” He ranges across Europe, up and down the geological column, offering suggestions for empirical work: study recent alluvial deposits of the Po and the Arno, dig in the gypsum quarries of Aix and Paris, collect “gryphites, the cornua ammonis and the entrochi” that may abound in the Black Forest. “We are as yet uninformed of the real position of the stinkstone slate of Oeningen, which is also said to be full of the remains of fresh-water fish.”

A man who could end one of the greatest

theoretical

treatises in natural history with a plea for unraveling the stratigraphic position and faunal content of the Oeningen stinkstones knew, in the most profound way, what science is about. We may wallow forever in the thinkable; science traffics in the doable.

I ONCE HAD

a gutsy English teacher who used a drugstore paperback called

Word Power Made Easy

instead of the insipid fare officially available. It contained some nifty words, and she would call upon us in turn for definitions. I will never forget the spectacle of five kids in a row denying that they knew what “nymphomania” meant—the single word, one may be confident, that everyone had learned with avidity. Sixth in line was the class innocent; she blushed and then gave a straightforward, accurate definition in her sweet, level voice. Bless her for all of us and our cowardly discomfort; I trust that all has gone well for her since last we met on graduation day.

Nymphomania titillated me to my pubescent core, but two paired words from the same lesson—anachronism and incongruity—interested me more for the eerie feeling they inspired. Nothing elicits a greater mixture of fascination and distress in me than objects or people that seem to be in the wrong time or place. The

little

things that offend a sense of order are the most disturbing. Thus, I was stunned in 1965 to discover that Alexander Kerensky was alive, well, and living as a Russian émigré in New York. Kerensky, the man who preceded the Bolsheviks in 1917? Kerensky, so linked with Lenin and times long past in my thoughts, still among us? (He died, in fact, in 1970, at age 89.)

In July 1981, on a ship headed for the Galápagos Islands, I encountered an incongruity that struck me just as forcefully. I was listening to a lecture when a throwaway line cut right into me. “Louis Agassiz,” the man said, “visited the Galápagos and made scientific collections there in 1872.” What? The primal creationist, the last great holdout against Darwin, in the Galápagos, the land that stands for evolution and prompted Darwin’s own conversion? One might as well let a Christian into Mecca. It seems as incongruous as a president of the United States portraying an inebriated pitcher in the 1926 World Series.

Louis Agassiz was, without doubt, the greatest and most influential naturalist of nineteenth-century America. A Swiss by birth, he was the first great European theorist in biology to make America his home. He had charm, wit, and connections aplenty, and he took the Boston Brahmins by storm. He was an intimate of Emerson, Longfellow, and anyone who really mattered in America’s most patrician town. He published and raised money with equal zeal and virtually established natural history as a professional discipline in America; indeed, I am writing this article in the great museum that he built.

But Agassiz’s summer of fame and fortune turned into a winter of doubt and befuddlement. He was Darwin’s contemporary (two years older), but his mind was indentured to the creationist world view and the idealist philosophy that he had learned from Europe’s great scientists. The erudition that had so charmed America’s rustics became his undoing; Agassiz could not adjust to Darwin’s world. All his students and colleagues became evolutionists. He fretted and struggled, for no one enjoys being an intellectual outcast. Agassiz died in 1873, sad and intellectually isolated but still arguing that the history of life reflects a preordained, divine plan and that species are the created incarnations of ideas in God’s mind.

Agassiz did, however, visit the Galápagos a year before he died. My previous ignorance of this incongruity is at least partly excusable, for he never breathed a word about it in any speech or publication. Why this silence, when his last year is full of documents and pronouncements? Why was he there? What impact did those finches and tortoises have upon him? Did the land that so inspired Darwin, fueling his transition from prospective preacher to evolutionary agnostic, do nothing for Agassiz? Is not this silence as curious as the basic fact of Agassiz’s visit? These questions bothered me throughout my stay in the Galápagos, but I could not learn the answers until I returned to the library that Agassiz himself had founded more than a century ago.

Agassiz’s friend Benjamin Peirce had become superintendent of the Coast Survey. In February of 1871, he wrote to Agassiz offering him the use of the

Hassler

, a steamer fit for deep-sea dredging. I suspect that Peirce had a strong ulterior motive beyond the desire to collect some deep-sea fishes: he hoped that Agassiz’s intellectual stagnation might be broken by a long voyage of direct exposure to nature. Agassiz had spent so much time raising money for his museum and politicking for natural history in America that his contact with organisms other than the human kind had virtually ceased. Agassiz’s life now belied his famous motto: study nature, not books. Perhaps he could be shaken into modernity by renewed contact with the original source of his fame.

Agassiz understood only too well and readily accepted Peirce’s offer. Agassiz’s friends rejoiced, for all were saddened by the intellectual hardening of such a great mind. Darwin himself wrote to Agassiz’s son: “Pray give my most sincere respects to your father. What a wonderful man he is to think of going round Cape Horn; if he does go, I wish he could go through the Strait of Magellan.” The

Hassler

left Boston in December 1871, moved down the eastern coast of South America, fulfilled Darwin’s hope by sailing through the Strait of Magellan, passed up the western coast of South America, reached the Galápagos (at the equator, 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador) on June 10, 1872, and finally docked at San Francisco on August 24.

A possible solution to the enigma of Agassiz’s silence immediately suggests itself. The Galápagos are pretty much “on the way” along Agassiz’s route. Perhaps the

Hassler

only stopped for provisions—just passing by. Perhaps the cruise was so devoted to deep-sea dredging and Agassiz’s observations of glaciers in the southern Andes that the Galápagos provided no special interest or concern.

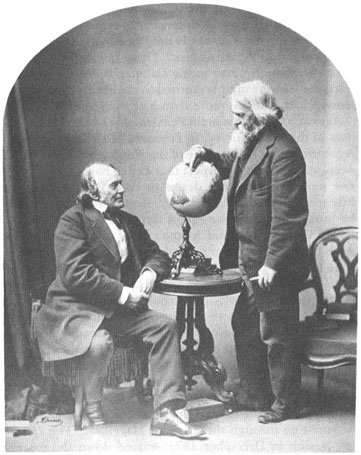

Agassiz, left, and his friend Benjamin Peirce, who arranged for his voyage to the Galápagos.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE GRANGER COLLECTION

.

This easy explanation is clearly incorrect. In fact, Agassiz planned the

Hassler

voyage as a test of evolutionary theory. The dredging itself was not designed merely to collect unknown creatures but to gather evidence that Agassiz hoped would establish the continuing intellectual validity of his lingering creationism. In a remarkable letter to Peirce, written just two days before the

Hassler

set sail, Agassiz stated exactly what he expected to find in the deep dredges.

Agassiz believed that God had ordained a plan for the history of life and then proceeded to create species in the appropriate sequence throughout geological time. God matched environments to the preconceived plan of creation. The fit of life to environment does not record the evolutionary tracking of changing climates by organisms, but rather the construction of environments by God to fit the preconceived plan of creation: “the animal world designed from the beginning has been the motive for the physical changes which our globe has undergone,” Agassiz wrote to Peirce. He then applied this curiously inverted argument to the belief, then widespread but now disproved, that the deep oceans formed a domain devoid of change or challenge—a cold, calm, and constant world. God could only have made such an environment for the most primitive creatures of any group. The deep oceans would therefore harbor living representatives of the simple organisms found as fossils in ancient rocks. Since evolution demands progressive change through time, the persistence of these simple and early forms will demonstrate the bankruptcy of Darwinian theory. (I don’t think Agassiz ever understood that the principle of natural selection does not predict global and inexorable progress but only adaptation to local environments. The persistence of simple forms in a constant deep sea would have satisfied Darwin’s evolutionary theory as well as Agassiz’s God. But the depths are not constant, and their life is not primitive.)

The letter to Peirce displays that mixture of psychological distress and intellectual pugnacity so characteristic of Agassiz’s opposition to evolution in his later years. He knows that the world will scoff at his preconceptions, but he will pursue them to the point of specific predictions nonetheless—the discovery of “ancient” organisms alive in the deep sea:

I am desirous to leave in your hands a document which may be very compromising for me, but which I nevertheless am determined to write in the hope of showing within what limits natural history has advanced toward that point of maturity when science may anticipate the discovery of facts. If there is, as I believe to be the case, a plan according to which the affinities among animals and the order of their succession in time were determined from the beginning…if this world of ours is the work of intelligence, and not merely the product of force and matter, the human mind, as a part of the whole, should so chime with it, that, from what is known, it may reach the unknown.

But Agassiz did not sail only to test evolution in the abstract. He chose his route as a challenge to Darwin, for he virtually retraced—and by conscious choice—the primary part of the

Beagle

’s itinerary. The Galápagos were not a convenient way station but a central part of the plot. His later silence becomes more curious.

The

Beagle

did circumnavigate the globe, but Darwin’s voyage was basically a surveying expedition of the South American coast. Agassiz’s route therefore retraced the essence of Darwin’s pathway—physically if not intellectually. One cannot read Elizabeth Agassiz’s account of the

Hassler

expedition without recognizing the uncanny (and obviously not accidental) similarity with Darwin’s famous account of the

Beagle

’s voyage. (Elizabeth accompanied Louis on the trip.) Darwin concentrated primarily upon geology and so did Agassiz. The trip may have been advertised as a dredging expedition, but Agassiz was most interested in reaching southern South America to test his theory of a global ice age. He had studied glacial striations and moraines in the Northern Hemisphere and had determined that a great ice sheet had once descended from the north. (Striations are scratches on bedrock made by pebbles frozen into the bases of glaciers. Moraines are hills of debris pushed by flowing ice to the fronts and sides of glaciers.) If the ice age had been global, striations and moraines in South America would indicate a spread from Antarctica at the same time. Agassiz’s predictions were, in this case, upheld—and he exulted in copious print (faithfully transcribed by Elizabeth and published in the

Atlantic Monthly

).

Darwin was appalled by the rude life and appearance of the “savage” Fuegians and so was Agassiz. Elizabeth recorded their joint impressions: “Nothing could be more coarse and repulsive than their appearance, in which the brutality of the savage was in no way redeemed by physical strength or manliness…. They scrambled and snatched fiercely, like wild animals, for whatever they could catch.”

If there be any lingering doubt about Agassiz’s conscious decision to evaluate Darwin by retracing his experiences, consider this passage, written at sea to his German colleague Carl Gegenbaur:

I have sailed across the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Magellan, and along the western coast of South America to the northern latitudes. Marine animals were, naturally, my primary concern, but I also had a special purpose. I wanted to study the entire Darwinian theory, free from all external influences and former surroundings. Was it not on a similar voyage that Darwin developed his present opinions! I took few books with me…primarily Darwin’s major works.

I can find few details about Agassiz’s stay in the Galápagos. We know that he arrived on June 10, 1872, spent a week or more, and visited five islands, one more than Darwin did. Elizabeth claims that Louis “enjoyed extremely his cruise among these islands of such rare geological and zoological interest.” We know that he collected (or rather sat on the rocks while his assistants gathered) the famous iguanas that go swimming in the ocean to eat marine algae (some of his specimens are still in glass jars in our museum). We know that he crossed and greatly admired the bare fields of recently cooled ropy lava “full of the most singular and fantastic details.” I walked across a similar field, one that Agassiz could not have seen since it formed during the 1890s. I was mesmerized by the frozen signs of former activity—the undulating, ropy patterns of flow, the burst bubbles, and lengthy cracks of contraction. And I saw Pele’s tears, the most beautiful geological object, at small scale, that I have ever witnessed. When highly liquid lava is ejected from small vents, it may emerge as droplets of basalt that build drip castles of iridescent stone about their outlet—tears from Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes (not from Martinique’s Mount Pelée, which has an extra

e

).

Thus, I return to my original inquiry: if Agassiz went to the Galápagos as a central part of his plan to evaluate evolution by putting himself in Darwin’s shoes, what effect did Darwin’s most important spot have upon him? In response to this question we have only Agassiz’s public silence (and one private communication, to which I will shortly return).