He Wanted the Moon (27 page)

Read He Wanted the Moon Online

Authors: Mimi Baird,Eve Claxton

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Bipolar Disorder, #Medical

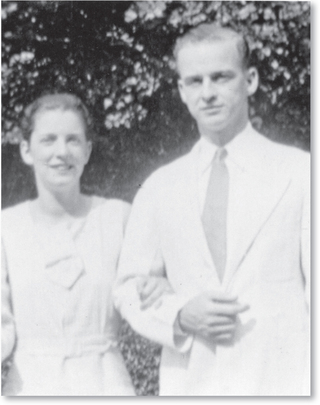

I asked if she remembered when my father asked her to marry him.

“Yes, of course,” she replied. “It was on Newbury Street. He put a diamond ring on my finger. It was his grandmother’s. Afterward he slipped into a phone booth and called his grandmother. He said: ‘I just put your ring on my dear Gretta’s finger.’ I can hear those words just as plain now as then.”

I sensed from her smiles that my parents had once, long ago, been very much in love and had been happy, for a time.

As I grew ever more immersed in my research, I realized that in order to have the fullest picture of what had happened between my parents, I needed to have a better understanding of my grandfather’s mental illness. When my mother met Perry on a blind date in Boston, did she recognize something of her long-lost father in him?

I applied for Henry’s—my grandfather’s—medical records from the mental institution in Norristown, Pennsylvania, where he spent most of his life, in the hopes that the records would offer additional insights. As I scanned the pages, the following entry stopped me in my tracks:

Norristown State Hospital, 1943

June 8: Patient, in a hypo-manic state, is visited today by his son-in-law, Dr. Perry Baird, who put him on a bus to visit his daughter in Massachusetts. Patient was returned on a train from Boston on June 24, 1943. He was most apologetic.

So my father had helped his father-in-law escape and gain a few weeks of respite from his hospital cell. A year later, my own father was locked away at Westborough. At this point, my mother shut down, refusing to speak of what had happened, exactly as her own mother had done.

Beginning in 1997, my mother experienced several mini-strokes, which further compromised the quality of her life and made her increasingly forgetful. Physically she looked just the same, but she became less careful about her appearance, and much slower in her motions. In 1999, I was called by the facility where she lived, Clark House, and told she had slipped into a semiconscious state. I traveled to see her, wondering if it would be the last of such journeys. Upon arrival, I went directly to her room and found her resting, unresponsive. The nurse told me that her heart was still strong and reassured me that I could return to Vermont later that afternoon.

Early the following day, the nurse called again to say her condition had weakened and that I should return. My sister was on vacation, so I called my daughter and two nieces and asked them to meet me at Clark House. Although my mother was barely conscious, the four of us quietly spoke to her. We assured her that all was well in the family and that we understood it was time for her to go. Occasionally her eyes opened and she turned slightly on her bed. At times she appeared unsettled, restless.

After a while, my daughter and her cousins went out of the room to find some nourishment. I sat at my mother’s side, continuing to quietly speak to her. Suddenly, she opened her eyes wide, looking directly into my own.

“I apologize,” she said, her voice suddenly strong and direct. “I am very sorry.” Her eyes closed slowly. After that, her restlessness seemed to ease. Within an hour she was gone. It was January 17, 1999.

In the weeks to come, I attempted to understand why she had apologized to me in those final hours. Could she have been acknowledging that she could have shared more of my father’s story with me, and that now it was too late?

My mother’s death presented me with a stark choice. I could carry our family secrets to the grave, as she had done—like her mother before her—or I could attempt to hold them up to the light and air.

For the next decade, I kept returning to this book. I had retired from my job at the hospital and was becoming ever more engrossed by new work with a local charitable foundation, and so the writing progressed in fits and starts. Then, in the winter of 2011, I received a call from my daughter, Meg. She had been assisting one of her sons with a homework assignment that required him to trace his family’s genealogy. Meg had described the various branches of our family and their history to my grandson, and then Googled my father’s name for good measure. This was how she discovered that a book existed containing a reference to my father and his research. It was by Dr. Elliot Valenstein, and it was titled

Blaming the Brain: The Truth about Drugs and Mental Health.

Meg read Dr. Valenstein’s words aloud to me on the telephone: “John Cade was not the first person to search for a biochemical basis of mania by injecting experimental animals with fluids obtained from mental patients. Perry Baird, at the time a successful Boston dermatologist who suffered from a manic depressive disorder, injected blood from a manic patient into adrenalectomized animals.”

Blaming the Brain

had recently been reprinted with its references amended to include my father’s name and his achievement. Dr. Valenstein also cited my father’s 1944 article and my synopsis of his manuscript in

Psychiatric Services

in 1996.

My daughter was jubilant. So was I. Perry Baird’s name had found its way into medical history, in a footnote, it’s true, but nonetheless his contribution had been recognized.

During this same period, I came across a letter I had never noticed before, tucked among the pages of my father’s manuscript. It was written in August of 1944, soon after his escape from Westborough, and it was addressed to Reverend Corny Trowbridge, our minister at Chestnut Hill. I remembered Corny’s kindness to my father, visiting him while he was in the hospital and sending him a copy of a book about St. Francis. Evidently my father had begun a correspondence with the reverend soon after.

In the letter, my father returns to the idea that his life may hold some greater purpose:

Dear Corny,

Your letter written from the Saranac Inn was a powerful communication. As with all of your letters, I have found it profitable to read your last letter several times and I have found much enjoyment in listening to what you had to say. I find great comfort in your belief that my recent reversal of fortune may lead “in the end to something of great worth.” The stormy course of my life during the last twelve years has proved to me that many good fortunes lie concealed in apparent disasters. Certainly in wrestling with adversity one learns to attain added courage and strength, and one learns to find beauty wherever it may be found regardless of the background.

Strange as it may seem, my periods of so-called illness are usually associated with certain productive powers not ordinarily available to me. Certain

new abilities have come to light during my manic attacks. Perhaps this is a clue to the “something of great worth” which may come out of these misfortunes. Out of the cauldron of despair, came forth a rather lengthy manuscript which one expert describes as a “magnificent work of art.” I am not convinced that the book deserves this amount of praise but I do know that in it, I have attained a style of expression that was available to me only during “illness.”

To finish this book is the one thing that I most want to do in life and I am working on the project now. It will involve telling the story of manic-depressive insanity, weaving in the lives of many really notable people who have suffered from it, recounting my own story. There will be commentaries upon modern hospital care with its queer barbarities and shortcomings, messages for friends and relatives of persons so afflicted, lines of reasoning, argument and education, built up in the hope of improving the general viewpoint about this type of insanity, perhaps improving general tolerance for it.

To reduce or remove certain prejudices would make worthwhile all efforts spent in writing the book. The book is already quite a long one and yet I haven’t come anywhere near the end. There will come a time to cut out parts here and there. It will probably require several more years to complete the job in the right way.